- There is a general consensus that jack the Ripper had five victims.

- The time period of his murders was between August 31st, 1888 and November 9th, 1888 .

- However, the five Jack the Ripper murders belonged to a generic police file titled "The Whitechapel Murders.".

- This actually contained the names of eleven victims and had a date range of April, 1888 to February, 1891.

- Site Author and Publisher Richard Jones

- Richard Jones

THE VICTIMS OF JACK THE RIPPER

THEIR LIVES, MURDERS AND FINAL RESTING PLACES

Between April, 1888 and February, 1891, eleven women were murdered in the East End of London, and their names were included in a police file that was officially titled, "The Whitechapel Murders."

Five of those women are believed to have been killed by one man, who has passed into history under the name of Jack the Ripper, so called from the signature of a taunting letter that was sent to the Central News Office on New Bridge Street in the City of London, during the last week of September, 1888.

These five women are often referred to as the "Canonical Five", victims of Jack the Ripper, and they were murdered over a nine week period between Friday the 31st of August and Friday the 9th of November, 1888.

They are buried in four East London cemeteries, in this article, we visit their final resting places, whilst, at the same time, revealing something about the tragedy of their live and the horror of their deaths.

THE CITY OF LONDON CEMETERY

We began our journey in the City of London Cemetery where a plaque in the memorial garden remembers Jack the Ripper's first victim Mary Nichols.

As with the majority of the victims, she was buried in an unmarked grave, and her actual resting place has long since been reused several times over.

But, since 1996, the Cemetery authorities have maintained a plaque to her.

MARY ANN NICHOLS

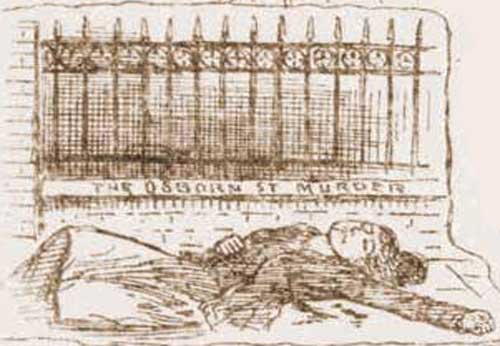

On the 31st of August, 1888, the horrifically mutilated body of a woman was found in a gateway in Buck's Row in Whitechapel.

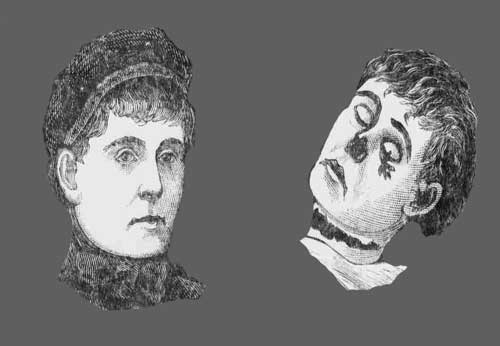

Later that day, she was identified as Mary Ann Nichols, better known to her family, friends and acquaintances as "Polly" Nichols.

She had separated from her husband and five children in 1880, and thereafter her life became a downward spiral, blighted by poverty and alcoholism.

By the beginning of August, 1888, she had found her way to the East End of London, where she resided at two Spitalfields common lodging houses, Wilmott's, situated at 18, Thrawl Street, and The White House, located on Flower and Dean Street.

The cost of a night's lodging in these establishments was fourpence. But, on the night of the 30th of August, she didn't even have this meager amount and was, therefore, denied a night's doss at Wilmott's common lodging house.

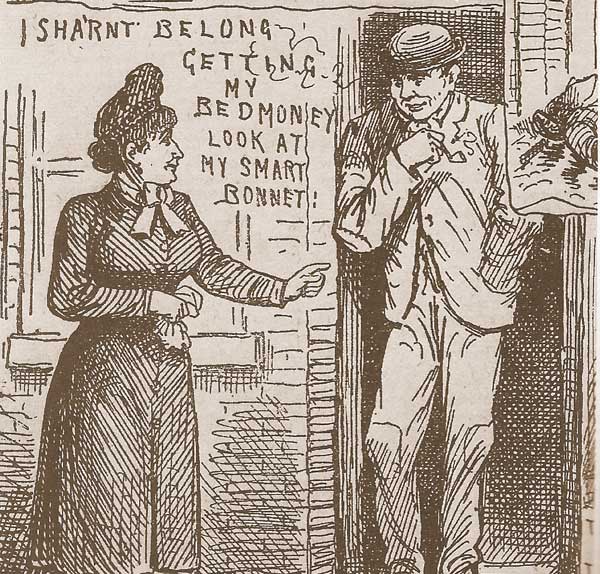

HER "JOLLY BONNET"

Mary Nichols was what was known at the time as an "unfortunate", a woman who, in the days when there was no welfare system to help those who had fallen on hard times, might turn to casual prostitution in order to raise the money for a bed, a bite to eat, and drink to feed her addiction.

That night Mary was wearing a bonnet that none of the other residents of the lodging house had seen her with before, and, since she was evidently intending to resort to prostitution in order to raise the money for her bed, she felt that this would be an irresistible draw to potential clients, and so, as she was escorted from the premises by the deputy lodging house keeper, Polly laughed to him, "I'll soon get my doss money, see what a jolly bonnet I have now."

So saying, she headed off into the early morning.

THE LAST TIME SHE WAS SEEN ALIVE

At 2.30 on the morning of August 31st, a friend of hers by the name of Emily Holland met her by the shop at the junction of Osborn Street and Whitechapel Road.

Mary was very drunk, and she boasted to Emily that she had made her lodging money three times over, but had spent it.

Concerned at Mary's drunken state, Emily tried to persuade her to come back to Wilmott's with her. Mary refused, and, telling Emily that she must get her lodging money somehow, she stumbled off along Whitechapel Road.

That was the last time that Mary Nichols was seen alive.

HER BODY FOUND IN BUCK'S ROW

At 3.45 a.m. the body of a woman was found lying next to a gateway in Buck's Row, Just off Whitechapel Road, and around ten minutes walk from the corner where Mary had met Emily Holland.

The woman's throat had been cut back to the spine, the wound being so savagely inflicted that, according to some newspaper reports, it had almost severed her head from her body.

THE DISCOVERY AT THE MORTUARY

Within 45 minutes, she had been placed on a police ambulance, which in reality was nothing more than a wooden hand cart, and had been taken to the mortuary of the nearby Whitechapel Workhouse Infirmary.

Here, Inspector Spratling, of the Metropolitan Police's J Division, arrived to take down a description of the, at the time, unknown victim, and he made the horrific discovery that, in addition to the dreadful wound to the throat, a deep gash ran all the way along the woman's abdomen - she had been disembowled.

HER FAMILY VISIT THE MORTUARY

Later that day, the woman's name had been ascertained as being Mary Ann Nichols, and her father, Edward Walker, was traced and taken to the mortuary, where he formally identified the body of the Buck's Row victim as that of his daughter.

With him went Mary's eldest son, also named Edward, who recognised her as his mother.

An hour later, her estranged husband, William Nichols, arrived and went into the mortuary to view her body. Genuinely distressed by what he saw, he shook his head disbelievingly, and whispered to her, "I forgive you, as you are, what you have been to me."

According to one newspaper, he emerged from the mortuary ashy white, and sighed, "Well, there is no mistake about it. It has come to a sad end at last."

THE FUNERAL OF MARY ANN NICHOLS

The funeral of Mary Ann Nichols took place amidst great secrecy, in order to deter morbid sightseers, on Thursday, 6th September, 1888.

The South Wales Echo published a report on it the next day:-

The time at which the cortege was to start was kept secret, and a ruse was resorted to in order to get the body out of the mortuary, where it has lain since the day of the murder.

A pair-horsed closed hearse was observed making its way down Hanbury-street and the crowds, which numbered some thousands, made way for it to go along Old Montague-street, but instead of so doing it passed on into Whitechapel-road, and doubling back it reached the mortuary by the back gate, which is situated in Chapman's-court.

No person was near other than the undertaker and his men when the coffin, which bore a plate with the inscription, "Mary Ann Nichols, aged 42. Died August 31, 1888." was removed to the hearse and driven off to Hanbury-street, there to await the mourners.

Meantime, the news had spread that the body was in the hearse, and people flocked round to see the coffin.

At length the cortege started towards Ilford. The mourners were Mr Edward Walker, the father of the deceased, and his grandson, together with two of the deceased's children.

The procession proceeded along Bakers-row, and past the corner of Buck's-row, into the main road, where policemen were stationed every few yards.

The houses in the neighbourhood had the blinds drawn, and much sympathy was expressed for the relatives."

Source: The South Wales Echo Friday, 7th September, 1888.

A STRANGE COINCIDENCE

Strangely, the ruse that was resorted to in order to get the body of Mary Nichols to the undertaker's could be said to have included an element of precognition.

For Mary Nichols's body was brought out of the mortuary's back gate in Chapman's Court, from where it was taken to the undertaker's premises on Hanbury Street.

Two days later, the murderer would strike again and would murder Annie Chapman in Hanbury Street.

VISITORS TO THE PLAQUE

Today, people from all over the world make the journey out to the City of London Cemetery to pay their respects to the memory of poor "Polly" Nichols.

Many of them leave flowers on the plaque, whilst others place coins there, presumably in remembrance of the fact that had she had the fourpence to pay for her bed at the lodging house she would not have fallen into the clutches of Jack the Ripper.

THE MURDER OF ANNIE CHAPMAN

Fifteen or so minutes walk from the City of London Cemetery, you will find Manor Park Cemetery, where a small memorial remembers Jack the Ripper's second victim, Annie Chapman, who was nicknamed "Dark Annie."

Like Mary Nichols, Annie had also seen a downward spiral due to alcoholism, and she had left her husband, John Chapman, and her children several years previously.

John would send her periodic allowances until his death in 1886, whereupon Annie supported herself by selling her own crochet work, as well as matches and flowers, supplementing her earnings with casual prostitution.

RESIDING IN DORSET STREET

By September, 1888, she was living, on and off, at Crossingham's lodging house, on Dorset Street, in Spitalfields.

She appears to have enjoyed a cordial relationship with the other tenants, and the deputy keeper, Timothy Donovan, remembered her as being an inoffensive soul whose main weakness was a fondness for drink.

However, following a fight with another resident at the lodging house, in the last week of August, Annie had received a black eye, and had been left bruised about the chest and head, and she was in considerable pain.

HER LAST NIGHT

At 5 p.m. on Friday, 7th September, Annie met her friend, Amelia Palmer in Dorset Street. Annie looked extremely unwell, and complained of feeling "too ill to do anything."

Amelia met her again, ten minutes later, still standing in the same place, although Annie was by then trying desperately to rally her spirits. "It's no use giving way, I must pull myself together and get some money or I shall have no lodgings," were the last words Amelia Palmer heard Annie Chapman speak.

At 11.30 p.m. that night, Annie turned up at Crossingham's lodging house, and asked Timothy Donovan if she could sit in the kitchen.

Since he hadn't seen her for a few days, Donovan asked her were she had been? "In the infirmary," she replied, weakly. He allowed her to go to the kitchen, where she remained until the early hours of Saturday morning, the 8th of September, 1888.

At 1.45 a.m., Donovan sent John Evans, the lodging house's night watchman to collect the fourpence for her bed from her. He found her, a little tipsy and eating potatoes in the kitchen. When he asked her for the money, she replied, wearily, "I haven't got it. I am weak and ill and have been in the infirmary."

Annie then went to Donovan's office and implored him to allow her to stay a little longer. He told her that if she couldn't pay, she couldn't stay.

Annie turned to leave, but then, turning back, she told him to save the bed for her, adding that, "I shall not be long before I am in. I shall soon be back, don't let the bed."

John Evans then escorted her from the premises, and watched her head off along Dorset Street, observing later that she appeared to be slightly tipsy as opposed to drunk.

HER BODY FOUND IN HANBURY STREET

At 5.30 that morning, Elizabeth Long saw her talking with a man outside number 29, in Hanbury Street, but, since there was nothing suspicious about the couple, she continued on her way, hardly taking any real notice.

30 minutes later, at 6 a.m., John Davis an elderly resident of number 29, found her horrifically mutilated body lying between the steps and the fence in the backyard of the house.

She was later identified by her younger brother, Fountain Smith.

THE FUNERAL OF ANNIE CHAPMAN

The funeral of Annie Chapman took place early on the morning of Friday, 14th September, 1888.

As with the funeral of Mary Nichols, a great deal of secrecy was observed in order to prevent crowds of curious onlookers following the procession.

The utmost secrecy was observed in the arrangements, and none but the undertaker, the police, and the relatives of the deceased knew anything about it.

Shortly after seven o'clock, a hearse drew up outside the mortuary in Montagu-street and the body was quickly removed.

At nine o'clock a start was made for Manor Park Cemetery, the place selected by the friends of the deceased for the interment, but no coaches followed, as it was desired that public attention should not be attracted.

Mr. Smith and other relatives met the body the cemetery, and the service was duly performed in the ordinary manner.

The remains of the deceased were enclosed in a black covered elm coffin, which bore the words, "Annie Chapman, died September 8, 1888, aged 48 years."

Source:- The Globe Friday, 14th September 1888.

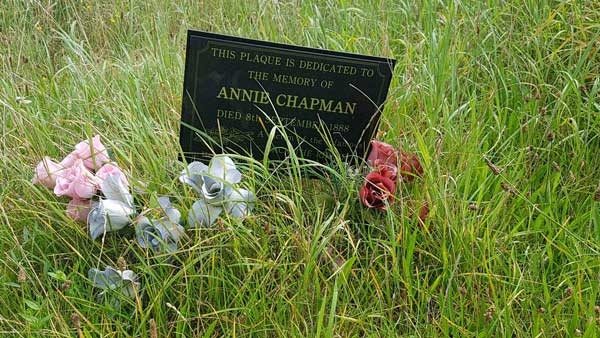

HER FINAL RESTING PLACE

The section of the cemetery in which she was buried has been reused several times since then, and so her exact resting place is now unknown.

In recent years, the graves that were here have been cleared away, and the area in general is now awaiting redevelopment.

A small plaque by a grassy mound is all that now remembers the interment of Annie Chapman, although there is some controversy over whether it is appropriative to have the nickname for her murderer included on it.

ANNIE'S LEGACY

If there was any legacy from the horrific and brutal murder of Annie Chapman, it was that the newspapers, and through them the public at large, began to pay attention to the plight of the poor women of the class from which Annie had come.

It didn't go unnoticed that, like Mary Nichols before her, Annie Chapman had died for the sake of fourpence that would have paid for her bed.

The Daily Telegraph emphasized this point:-

Dark Annie's spirit still walks Whitechapel, unavenged by justice...[her] dreadful end has compelled a hundred thousand Londoners to reflect what it must be like to have no home at all except the 'common kitchen' of a low lodging-house; to sit there, sick and weak and bruised and wretched, for lack of fourpence with which to pay for the right of a 'doss'; to be turned out after midnight to earn the requisite pence, anywhere and anyhow; and in the course of earning it to come across your murderer and to caress your assassin."

THE MURDER OF ELIZABETH STRIDE

Elizabeth Stride was born Elisabeth Gustafsdotter, in Sweden on the 27th November, 1842.

In 1866, she emigrated to England, arriving in London on the 7th of February that year.

Three years later, on the 7th of March, 1869, she married John Thomas Stride at the church of St. Giles-in-the-Fields, Holborn, and the newlyweds moved to the East End of London, where they opened a coffee shop in Crisp Street Poplar.

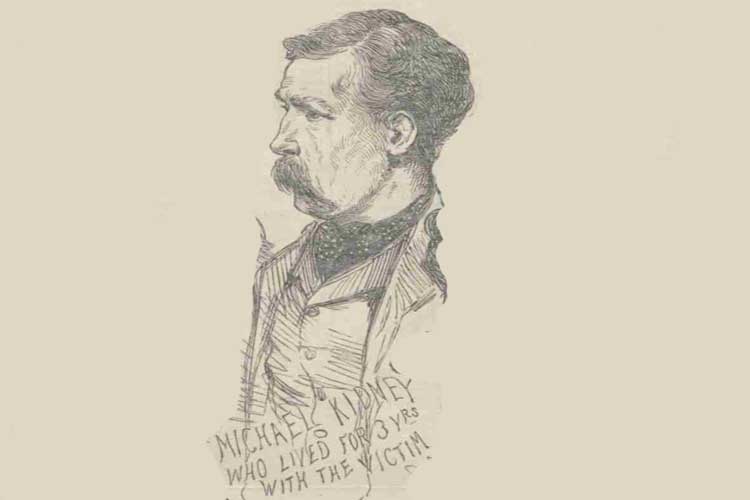

The couple separated around 1877, after which Elizabeth began residing at various common lodging houses; and she also became involved with a man by the name of Michael Kidney.

SHE ARRIVES IN SPITALFIELDS

Over the next few years, she began drinking heavily, and she made numerous appearances before magistrates on charges of being drunk and disorderly.

For the six years prior to her death, she had resided on and off at a common lodging house at 32 Flower and Dean Street in Spitalfields.

After a long absence, she had returned to the lodging house on the Tuesday before her death.

HER LAST NIGHT

On Saturday, 29th September, 1888, she had spent the afternoon cleaning two rooms at the lodging house, for which she was paid sixpence by the deputy keeper, and, by 6.30 p.m., she was enjoying a drink in the Queen's Head pub, at the junction of Fashion Street and Commercial Street.

Returning to the lodging house, she dressed ready for a night out, and, at 7.30 p.m. she left the lodging house.

There were several sightings of her over the course of the next five hour, and, by midnight, she had found her way to Berner Street, off Commercial Road.

At 12.45 a.m., on the 30th September, a man named Israel Schwartz saw her being attacked by a man in a gateway off Berner Street known as Dutfield's Yard. Schwarz, however, though he was witnesses sing a domestic argument and he crossed over the road to avoid getting dragged into the quarrel.

It is highly likely that Schwartz actually saw the early stages of her murder.

HER BODY FOUND IN DUTFIELD'S YARD

At 1 a.m. Louis Diemschutz, the Steward of a club that sided onto Dutfield's Yard came down Berner Street with his pony and costermongers barrow, and turned into the open gates of Dutfield's Yard. Immediately he did so, the pony shied and pulled left. Diemschutz looked into the darkness and saw a dark form on the ground. He tried to lift it with his whip, but couldn't. So, he jumped down and struck a match. It was wet and windy, and the match flickered for just a few seconds, but it was sufficient time for Diemschutz to see that it was a woman lying on the ground.

For some reason, he thought that the woman might be his wife, and that she was drunk, so he went into the club to get some help in lifting her up.

However, he found his wife in the kitchen, and so, taking a candle, he and several other members went out into the yard, and, by the candle's light, they were able to see a pool of blood gathering beneath the woman.

The police were sent for, and a doctor was summoned, who pronounced life extinct. It was noted that, although, as in the cases of the previous victims, the woman's throat had been cut, the rest of the body had not been mutilated. This led the police to deduce that Diemschutz had interrupted the killer when he turned into Dutfield's Yard.

The body was removed to the nearest mortuary - which still stands, albeit as a ruin, in the nearby churchyard of St George-in-the-East, and here she was identified as Elizabeth Stride.

THE FUNERAL OF ELIZABETH STRIDE

Elizabeth Stride was laid to rest in the East London Cemetery, Plaistow, on Saturday, 6th October, 1888, and her interment was given little attention by the press.

According to The Beverley and East Riding Recorder, her burial took place "in the quietest possible manner, and at the expense of the parish."

STATEMENT BY A SPIRITUALIST AT CARDIFF

However, on the night of her burial, a lady went to a police station in Cardiff, and made the bizarre claim that she had spoken with the spirit of Elizabeth Stride in the course of a séance, and the victim had identified her murderer.

The Somerset County Gazette reported on the extraordinary revelations a week later:-

An extraordinary statement bearing upon the Whitechapel tragedies was made to the Cardiff police on Saturday by a respectable looking elderly woman, who stated that she was a spiritualist, and, in company with five other persons, held a séance on Saturday night.

They summoned the spirit of Elizabeth Stride, and after some delay the spirit came, and, in answer to questions, stated that the murderer was a middle-aged man, whose name she mentioned, and who resided at a given number in Commercial-road or street, Whitechapel, and who belonged to a gang of twelve."

THE MURDER OF CATHERINE EDDOWES

Catherine Eddowes was born in Wolverhampton on the 14th of April, 1842, although her family moved to London when she was a young girl.

By the time she reached her mid-teens, both her parents had died, and she and her siblings were separated, with Catherine returning to Wolverhampton to live with an aunt.

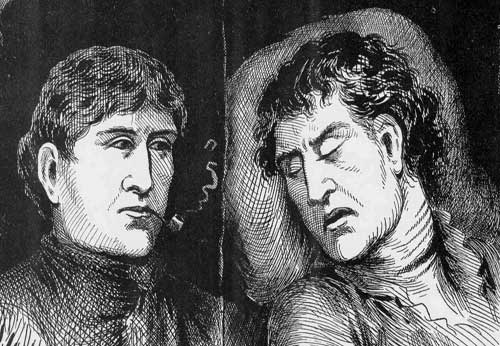

Later, she met a former soldier by the name of Thomas Conway, and it was claimed that the couple were married, although no proof of this has been found. She had his initials TC tattooed in blue ink on her arm.

The couple would have three children together, and they earned a meager income by selling what were known as chapbooks, which were cheap books sold on the streets by peddlers.

THEY MOVE TO LONDON AND SEPARATE

By the end of the 1870s the couple had moved to London, and were living in Westminster. Catherine, however, had started drinking heavily, and her alcoholism, coupled with her fiery temperament, meant that their relationship became extremely tempestuous and the couple repeatedly split up. According to one of Catherine's sisters Conway was an abusive partner and Catherine often sported black eyes as a result of domestic violence.

In 1880, they separated altogether, and Catherine gravitated to the East End of London, where she moved into Cooney's common lodging house at 55, Flower and Dean Street, and here, in 1881, she met a man named John Kelly, who earned his living as a casual labourer at the local markets.

The couple would live together as man and wife at the lodging house until Catherine's death in 1888. The deputy lodging house keeper, Frederick Wilkinson, would later remember her fondly as a very jolly woman who was often singing.

HOP PICKING IN KENT

Each summer, Catherine and Kelly would head for Kent to go hop picking, which was a popular way for Eastenders at the time to enjoy a break from the stifling and overcrowded streets of the district, whilst, at the same time, providing an opportunity to earn a little ready cash.

In September, 1888, they set off for their annual hop picking break; but, as the hop yield was disappointingly low that year, on account of the unusually wet summer, work was limited and they decided to return to London, arriving back in the capital on the afternoon of Friday, 28th September.

BACK TO LONDON

Kelly managed to earn sixpence that day, and Catherine, having taken two pence for herself, handed him fourpence, telling him to use it to get a bed at Cooney's that night. She told him that she would get a bed in the Casual Ward of the Shoe Lane Workhouse.

Although she did get a bed, there was some trouble at the workhouse, and she was asked to leave. She turned up at Cooney's at 8am on the Saturday morning, and the couple went to a pawn brokers shop on Church Street, where they pawned Kelly's boots, using the money to buy breakfast.

HER LAST DAY

That afternoon, Catherine told Kelly that she was going to try and borrow some money from her daughter in Bermondsey, and at 2pm they parted. According to Kelly's later testimony, he warned her about the Whitechapel murderer, but Catherine brushed aside his fears, "Don't you fear for me", she told him. "I'll take care of myself, and I shan't fall into his hands."

It was never established how she spent the rest of that afternoon. She certainly didn't visit her daughter. But she did acquire money somehow, because at 8pm that evening she was arrested for drunkenness on Aldgate High Street by Police Constable Robinson of the City of London Police.

ARRESTED FOR BEING DRUNK

She was taken to Bishopsgate Police Station where she was locked in a cell to sober up. She promptly fell fast asleep.

By midnight, she was awake and was deemed sober enough for release by the City gaoler PC George Hutt. Before leaving, she told him that her name was Mary Ann Kelly, and gave her address as 6 Fashion Street.

Hutt escorted her to the door of the police station, and he told her to close it on her way out. "Alright. Goodnight old cock" was her reply, as she headed out into the early morning.

HER MURDER

At 1.35 a.m. three men - Joseph Lawende, Joseph Hyam Levy and Harry Harris saw her talking with a man at the Church Passage entrance into Mitre Square, located on the eastern fringe of the City of London.

Ten minutes later, at 1.45 am. Police Constable Alfred Watkins walked his beat into Mitre Square and discovered her horrifically mutilated body lying in the darkness of the Square's South West corner.

As with the previous victims, her throat had been cut and she had been disembowled. But, in addition, the killer had targeted her face, carving deep Vs into her cheeks and eyelids. He had also removed and gone off with her uterus and left kidney.

And, as with the previous murders, he had once again melted away into the night.

FUNERAL OF CATHERINE EDDOWES

The funeral of Catherine Eddowes took place on the afternoon of Monday, 8th October 1888. Dense crowds gathered around the mortuary in Golden Lane in the City of London, and thousands of onlookers lined the streets that the funeral cortege was to pass through. meanwhile, around five hundred people arrived at the City of London Cemetery, where the burial was to take place.

Lloyd's Weekly Newspaper carried a full report on it the following Sunday:-

The remains of Catherine Eddowes, the victim of the Mitre-square tragedy, were interred on Monday afternoon at Ilford cemetery, a vast crowd following in procession.

The funeral cortege consisted of a hearse, a mourning coach, containing relatives and friends of the deceased, and a brougham conveying representatives of the Press.

The coffin was of polished elm, with oak mouldings, and bore a plate with the inscription. in gold letters, "Catherine Eddowes, died Sept. 30,1888, aged 43 years."

One of the sisters of the deceased laid a beautiful wreath on the coffin as it was placed in the hearse, and at the graveside a wreath of marguerites was added by a sympathetic kinswoman.

The mourners were the four sisters of the murdered woman, Harriet Jones, Emma Eddowes, Eliza Gold, and Elizabeth Fisher; her two nieces, Emma and Harriet Jones, and John Kelly, the man with whom she had lived.

The procession left the mortuary in Golden-lane at half- past one, passing through Old-street, Great Eastern-street. Commercial-street, Whitechapel-road, Mile-end-road, and Stratford to the City cemetery at Ilford.

In the cemetery men and women of all ages, many of the latter carrying infants in their arms, gathered round the grave.

The remains were interred in the Church of England portion of the cemetery, the service being conducted by the chaplain, the Rev. Mr. Dunscombe. Mr. G. C. Hawkes, a vestryman of St. Luke's, undertook the responsibility of carrying out the funeral at his own expense, and the City authorities, to whom the burial ground belongs, remitted the usual fees.

Since the 1990s, the Cemetery authorities have maintained a simple memorial plaque to her, and, as with the plaque to Mary Nichols on the opposite side of the path, people come here to remember her and to lay flowers and coins as close as it is now possible to get to the final resting place of Catherine Eddowes.

THE ENIGMATIC MARY KELLY

HER EARLY LIFE

And so we come to the last and, in many ways, the most enigmatic of Jack the Ripper's victims - Mary Jane Kelly.

She is the victim about whom we know the least.

In fact, we know virtually nothing about her life prior to her arrival in the East End of London, and what we do know is based on what she chose to reveal about her past to those she knew, and the veracity of what she did reveal is difficult to ascertain. Indeed, we don't even know for certain that her name actually was Mary Kelly.

According to her boyfriend, Joseph Barnett, with whom she lived until shortly before her death, she had told him that she was born in Limerick, in Ireland, that her father's name was John Kelly, and that she had six or seven brothers and one sister.

The family moved to Wales when she was a child, and when she was sixteen she met and married a collier named Davis or Davies. Three years later, her husband was killed in a mine explosion, and Mary moved to Cardiff to live with a female cousin who introduced her to prostitution.

Mary moved to London around 1884, where she made the acquaintance of a French woman who ran a high-class brothel in Knightsbridge, in which establishment Mary began working. She told Barnett that, during this period in her life, she had dressed well, had been driven about in a carriage, and, for a time, had led the life of a lady.

She had, she said, made several visits to France at this time, and had accompanied a gentleman to Paris, but, not liking it there, she had returned to London after just two weeks.

From then on she began using the continental version of her name, and often referred to herself as Marie Jeannette Kelly.

SHE ARRIVES IN THE EAST END

Thereafter, her life suffered a downward spiral, which saw her move to the East End of London, where she lodged with a Mrs. Buki, in a side thoroughfare off Ratcliff Highway. Soon after her arrival she enlisted her landlady's assistance in returning to the West End to retrieve a box which contained dresses of a costly description from the French lady.

Mary had now started drinking heavily, and this led to conflict between her and Mrs Buki, relations between them becoming so strained that Mary moved out and went to lodge at the home of Mrs. Mary McCarthy, at 1 Breezer's Hill, Pennington Street, St. George-in-the-East.

By 1886 she had moved into Cooley's common lodging house in Thrawl Street, and it was whilst living here that, on Good Friday, 6th April 1887, she met Joseph Barnett, who worked as a porter at Billingsgate Fish Market.

The two were soon living together and, by 1888, they were renting a tiny room at 13 Miller's Court from John McCarthy, who owned a chandlers shop just outside Miller's Court on Dorset Street.

LIKED BY THOSE WHO KNEW HER

An article that appeared in the Daily Telegraph shortly after her death described her as having been of "fair complexion, with light hair, and she possessed rather attractive features."

Those who knew Mary around this time seem to have been quite fond of her. According to one acquaintance she was an excellent scholar and an artist of no mean degree; whilst her friend Maria Harvey described her as, "much superior to most persons in her position in life."

Remembering her in his memoirs, in 1937, retired police officer Walter Dew claimed that he had known her quite well by sight, and he told how he would often see her "parading along Commercial Street, between Flower and Dean Street and Aldgate, or along Whitechapel Road. "She was," he continued, "usually in the company of two or three of her kind, fairly neatly dressed and invariably wearing a clean white apron, but no hat."

According to her landlord, John McCarthy, her only fault was that when in liquor she could be very noisy, but otherwise, he said, she was a very quiet woman.

BEHIND WITH HER RENT

She and Barnett appear to have lived happily together, until, in mid-1888, he lost his market job, and she returned to prostitution, which caused arguments between them, and during one heated exchange a pane in the window by the door of their room had been broken.

The precariousness of their finances had resulted in Mary falling behind with her rent, and by early November she owed her landlord twenty nine shillings in rent arrears.

On 30th October, 1888, Joseph Barnett moved out, although he and Mary remained on friendly terms, and he would drop by to see her, the last time being at around 7.30 on the evening of Thursday 8th November, albeit he didn't stay long.

THE LAST SIGHTING OF HER

Several people claimed to have seen her during the next fourteen hours

One of them was George Hutchinson, an unemployed labourer, who met her on Commercial Street at 2am on the 9th November. She asked him if he would lend her sixpence, to which he replied that he couldn't as he'd spent all his money.

Replying that she must go and find some money, she continued along Commercial Street, where a man coming from the opposite direction tapped her on the shoulder and said something to her, whereupon they both started laughing.

The man put his arm around Mary, and they started walking back along Commercial Street, passing Hutchinson who was standing under the lamp by the Queen's Head pub at the junction of Fashion Street and Commercial Street.

Although the man had his head down with his hat over his eyes, Hutchinson stooped down and looked him in the face, whereupon the man gave him what Hutchinson would later describe as a stern look.

Hutchinson followed them as they crossed into Dorset Street, and he watched them turn into Miller's Court. He waited outside the court for 45 minutes, by which time they hadn't reemerged, so he left the scene.

HER BODY FOUND IN HER ROOM

At around 4 a.m., two of Mary's neighbours heard a faint cry of "Murder", but because such cries were frequent in the area - often the result of a drunken brawl - they both ignored it.

At 10. 45 on the morning of the 9th November, her landlord, John McCarthy sent his assistant, Thomas Bowyer, round to Mary's room, telling him to try and get some rent from her.

Bowyer marched into Miller's Court and banged on her door. There was no reply. He tried to open it, but found it locked. He therefore went round to the broken window pane, reached in, pushed aside the shabby muslin curtain that covered it, and looked into the gloomy room

Moments later, an ashen faced Bowyer burst back into McCarthy's shop on Dorset Street. "Guvnor,", he stammered, "I knocked at the door and could not make anyone answer. I looked through the window and saw a lot of blood."

"Good God, you don't mean that", was McCarthy's reply, and the two men raced into Miller's Court, where McCarthy stooped down and looked through the broken pane of glass.

McCarthy would later recall the horror of the scene that greeted him. "The sight we saw I cannot drive away from my mind. It looked more the work of a devil than of a man. I had heard a great deal about the Whitechapel murders, but I declare to God I had never expected to see such a sight as this. The whole scene is more than I can describe. I hope I may never see such a sight as this again."

THE POLICE ARRIVE

The police were immediately sent for, and one of the first officers at the scene was Walter Dew, who, many years later would recall the horror of what he saw through that window:- "On the bed was all that remained of the young woman. There was little left of her, not much more than a skeleton. Her face was terribly scarred and mutilated. All this was horrifying enough, but the mental picture of that sight which remains most vividly with me is the poor woman's eyes. They were wide open, and seemed to be staring straight at me with a look of terror."

As news of another murder spread around the neighborhood, crowds of people converged at both ends of Dorset Street, and the police constables struggled to keep them at bay.

More detectives and doctors were now arriving at Miller's Court, but the police delayed entering the room, as they believed they had been ordered to wait for bloodhounds to be brought to the scene and put on the scent of the killer. But, just before 1.30pm. they received word that the order for bloodhounds had been countermanded, and they asked John McCarthy to force open the door, which he did with a pickaxe.

What they saw and smelt that afternoon, as they filed into the tiny room, would haunt many of those present for years afterwards, and the horror of the experience was succinctly expressed by one of the attending doctors who later told a journalist that he had seen a great deal in dissecting rooms, but had never witnessed such a horrible sight as that inside 13 Miller's Court.

The police and doctors spent the next few hours carrying out a detailed inspection of the crime scene. In addition, a photographer was brought in and the body was photographed as it lay on the bed. This horrific and haunting image still exists, and is one of the earliest crime scene photos that we have.

THE BODY TAKEN TO THE MORTUARY

Just before four on the Saturday afternoon, a horse and cart drew up on the opposite side of Dorset Street from Miller's Court, whereupon a large number of residents from the neighbouring properties turned out to watch as the remains of Mary Kelly were brought out in a long shell or coffin that was battered and scarred with constant use. It was placed on the cart and was then taken to the mortuary in the churchyard of St Leonard's Church, Shoreditch.

Once the body had been removed, the windows of 13 Miller's Court were boarded up, the door was padlocked shut and those who lived in the vicinity were left to come to terms with the horror that had occurred in their midst. Few of them could have slept soundly in their beds that night.

THE FUNERAL OF MARY KELLY

On the morning of Monday, 19th November, 1888, word got out that the funeral of Mary Kelly was to take place that day, and, from an early hour, crowds began congregating around St Leonard's Church, Shoreditch, where the body had remained in the neighbouring mortuary since the day of the murder.

At noon, the church bell began tolling, and, at 12.30 p.m., the coffin of polished elm and oak, on top of which were two crowns of artificial flowers and a floral cross, was carried out, borne on the shoulders of four men. The crowd, which by this time was several thousand strong, were greatly affected by the sight, and they surged forward to try and touch the coffin and to read its simple inscription "Marie Jeanette Kelly, died 9th Nov. 1888, aged 25 years."

A large contingent of police officers fought desperately to hold the crowd back as the coffin was placed on an open car, drawn by two horses, and the cortege, which also consisted of two mourning coaches, in one of which sat Joseph Barnett, set off for St Patrick's Roman Catholic cemetery in Leytonstone.

Dense crowds lined the way, and the escorting police constables struggled to clear a path for the cortege as it made slow progress towards the cemetery, where a hundred or so onlookers were awaiting it when it arrived just before 2pm.

Only the mourners were allowed to enter the cemetery, where the parish priest met them by the small chapel, and then, preceded by two acolytes and a cross-bearer, he led the way to the north-east corner of the burial ground where Mary Kelly was laid to rest.

THE LEGACY OF THE CRIMES

What nobody could have realised at the time was that, in the bloody carnage of that tiny room in Miller's Court the autumn of terror had reached its conclusion.

In the days and weeks that followed, the district returned to some semblance of normality. Yes, there would be further murders that were included in the Whitechapel Murders file, but there is now a general consensus that these were not carried out by Jack the Ripper.

As for the legacy of the crimes, they certainly did focus attention on the plight of the poor who lived in the area that would later be dubbed "The Abyss". But whether the murders helped bring about a change to the horrific social conditions, as is often claimed, is debatable.

Today, people come from all over the world to lay flowers, coins and other trinkets on and around the victims memorials and to spend a few quiet moments remembering Mary Ann Nichols, Annie Chapman, Elizabeth Stride, Catherine Eddowes and Mary Jane Kelly, five women whose horrific deaths force us to confront the tragedy and hardship of their lives.

And there, perhaps is the paradox on which to end our journey. For there can be no doubt that their names would have been long ago forgotten were it not for the fact that they were murdered by a man whose name we will now never know for certain.