- Mary Walker's date of birth was August 26th, 1845.

- When she was 18, in January, 1864, she married printer William Nichols.

- The couple would have five children together, before separating in 1880, after which Mary would spend many of the next a years flitting between various London workhouses.

- By August, 1888, Mary had found her way to the East End of London, where she became a resident at the common lodging houses that were prevalent in the district.

- On August 31st, 1888, she would become the first victim of Jack the Ripper.

- Site Author and Publisher Richard Jones

- Richard Jones

THE LIFE AND DEATH OF MARY NICHOLS

THE FIRST CANONICAL VICTIM

Mary Ann Nichols - or "Polly" Nichols as she was often called by her family, friends and acquaintances, was born Mary Ann Walker on the 26th of August, 1845, at Dawes Court, off Shoe Lane in the City of London.

She was the second of three children of Edward and Caroline Walker.

MARRIED WILLIAM NICHOLS

We know next to nothing about her early life, other than that, at some stage during her teenage years, she became involved with a boy of the same age as her by the name of Thomas Stuart Drew.

However, this teenage romance had ended by 1863, when she met a printer by the name of William Nichols.

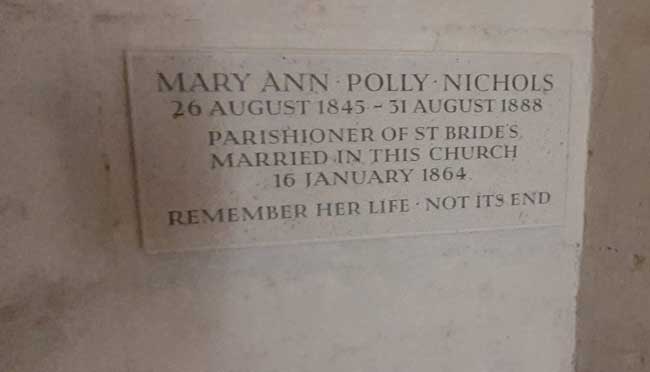

On the 16th of January, 1864, when she was eighteen, Mary married William Nichols in the church of St Bride's, Fleet Street, where a plaque on a wall inside the church now commemorates their union here.

The Plaque Remembering Mary's Marriage To William Nichols

St, Bride's, Fleet Street.

THEY LIVED IN BOUVERIE STREET

The newlyweds lived for a short time in Bouverie Street, off Fleet Street, before moving south of the river to live with her father, Edward Walker, at 131 Trafalgar Street, in Walworth, at which address they would reside for the next ten years.

The couple would have five children together - Edward John, born in 1866, Percy George, born in 1868, Alice Esther, born in 1870, Elizabeth Sarah, born in 1877, and Henry Alfred, born in 1879.

MOVES INTO PEABODY BUILDINGS

Around 1875, the family moved into their own flat in D Block, in Peabody Buildings, Stamford Street, in the Southwark district of South London. For this they paid a weekly rent of five shillings and ninepence.

Although the estate still survives, D Block was demolished in the 1970s in order to reduce the density of dwellings on the estate, and the children's play area now stands on its site.

The Peabody Buildings, Stamford Street.

SHE BEGAN DRINKING HEAVILY

Over the next five years, Mary began drinking heavily, and her mental state could not have been helped by the fact that her husband, William, had an affair with the woman who looked after Mary when she gave birth to their last child Henry Alfred.

According to Mary's father, William left Mary to live for a time with this woman, and it was, therefore, William's infidelity that lay behind their marital difficulties. William, on the other hand, maintained that it was Mary's drinking that was responsible, and he would later state that she had left him on several occasions.

Whoever was at fault, in September, 1880, the couple separated altogether and Mary moved out of the family home.

Their children remained with William, with the exception of their eldest son, Edward, who went to live with Mary's father.

A RESIDENT OF LAMBETH WORKHOUSE

William paid her a weekly maintenance allowance of five shillings, and Mary became a resident at Lambeth Workhouse, parts of which still survive close to Elephant and Castle in south London. She would reside at the Workhouse until the 31st of May 1881, when she left to move in with a man whose identity is unknown.

The Water Tower and Master's House of the former Lambeth Workhouse.

AN IMMORAL LIFE

Around this time, William claimed to have found out that she was leading an immoral life - presumably referring to the fact that she was living with another man, although some commentators hold that he meant that he had discovered that she was working as a prostitute.

Either way, he used this as an excuse to stop paying the maintenance allowance to her.

Mary appealed to the parish authorities, who intervened on her behalf and demanded that William pay her the outstanding money. He argued that she had deserted him, leaving him with their children to bring up, and pointing out that she was, in fact, now living with another man.

Mary lost the case, and William would, thereafter, only see her occasionally, the last time being about three years before her death in 1888.

MOVED IN WITH HER FATHER

By April, 1882, the relationship with the unidentified man was over, and, on the 24th of that month, she once again went to reside at Lambeth Workhouse, where she would remain until the 24th of March, 1883, when she moved back in with her father, Edward Walker, at 131 Trafalgar Street.

He also became somewhat perturbed by her heavy drinking. He would tell the inquest into her death that she was not a sober woman, and this had caused disagreements between them. He also stated that he did not think that she was promiscuous and she certainly didn't stay out particularly late at night. The worst he had seen of her, he said, was her keeping company with females of a certain class.

On the 21st of May, 1882, they argued over her drinking, and, the next day, she moved out and went to reside once again at Lambeth Workhouse.

THOMAS STUART DREW

In June 1883, she rekindled her relationship with Thomas Stuart Drew, who was by then a widower, and she moved in with him at the house and shop where he worked as a blacksmith at 15, York Street, Walworth, in South London.

Their relationship ended in 1887, when, according to later newspaper reports, Mary made away with some of his goods for drink and, having been abandoned by him, she, once more, began spending time at various workhouses, including her regular haunt at Lambeth.

SLEEPING ROUGH IN TRAFALGAR SQUARE

In October, 1887, Mary may have joined the hundreds of homeless who were sleeping rough in Trafalgar Square, many of whom ignored an order issued on Monday, the 23rd of October by the Metropolitan Police Commissioner, Sir Charles Warren to vacate the Square, and who were, therefore, arrested and charged with, "wandering abroad without any visible means of sustenance."

On the morning of Tuesday, 25th October, 1887, those who had been taken into custody the previous night appeared at Bow Street Police Court, and amongst them was a Mary Ann Nichols.

It isn't certain whether this was the Mary Ann Nichols who, within a year, would become the first of the canonical five victims of Jack the Ripper; but, if it was, the newspapers were somewhat unflattering about her, describing her as "the worst woman in the square", and going on to say that at the police station she was, "very disorderly."

A JOB AS A DOMESTIC SERVANT

Thereafter, Mary returned to flitting between workhouses, and, by April, 1888, she was back at Lambeth Workhouse. Here she befriended a girl by the name of Mary Anne Monk.

In early May, 1888, Mrs Fielder, the matron of the workhouse, helped Mary get a job working as a domestic servant in the household of Samuel and Sarah Cowdry, at "Ingleside", Rose Hill Road, Wandsworth.

Mary began working for the couple on the 12th of May, 1888, and from their house she wrote to her father, who had not seen her for two years, to tell him of her new situation, in which she seemed to have been quite content:-

I just write to say you will be glad to know that I am settled in my new place, and going on all right up to now. My people went out yesterday, and have not returned, so I am left in charge. It is a grand place inside, with trees and gardens back and front. All has been newly done up. They are teetotallers, and religious, so I ought to get on. They are very nice people, and I have not too much to do. I hope you are all right and the boy has work. So goodbye for the present.

From yours truly

"Polly".Answer soon, please, and let me know how you are."

Edward wrote a letter in reply, but he heard nothing more from his daughter.

SHE HAD ABSCONDED

Then, on the 12th of July, 1888, he received a postcard from Mrs Sarah Cowdry, informing him that his daughter had absconded and had stolen clothing worth in excess of £3. 10 shillings from her employers.

SHE MOVES TO THE EAST END

By early August, 1888, Mary Ann Nichols had made her way to the East End of London, where she moved into Wilmott's, a female only common lodging house located at 18 Thrawl Street, in Spitalfields. Here she was known to the other residents as, "Polly."

She shared a room with three other women, one of whom was an elderly lady by the name of Emily Holland - who was also referred to in some reports as Ellen Holland - with whom Mary became friendly.

Emily would later remember Mary as having been a "very clean woman", who kept herself to herself "as if she was melancholy" and who "gave her the impression of being weighed down by some trouble.". Although she did concede that she had seen Mary "the worse for drink once or twice," Emily also stated that Mary "never used to be fond of men", adding that, "I don't think she was a fast woman."

Wilmott's Lodging House, 18, Thrawl Street, Sketched in 1891.

MOVES TO FLOWER AND DEAN STREET

On the 24th of August, 1888, Mary left Wilmott's and went to reside at a mixed-sex common lodging house, known as "The White House", which was situated at 56, Flower and Dean Street, Spitalfields.

Here she would spend her last and forty-third birthday on Sunday the 26th of August, 1888.

It was never established how she spent the next four days, which would be last few days of her life.

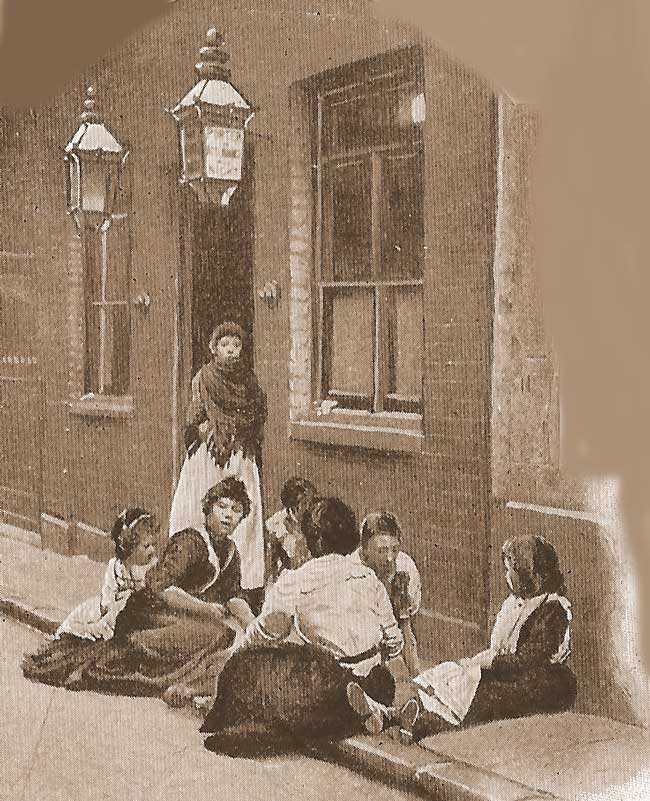

Women Outside The White House, Flower and Dean Street, 1901.

HEAVY THUNDER STORM IN LONDON

The morning of Thursday, 30th of August 1888 was, according to one newspaper, "magnificently fine", making a welcome change from the cold and wet conditions that had helped turn the summer of 1888 into one of the worst on record.

However, in the early afternoon, dark clouds gathered over London, and, at about half-past two, a heavy thunderstorm erupted, sending flashes of vivid bright lightning streaking across the sky, as the rain fell in torrents for several hours. In the East End of London, houses close to the River Thames were flooded, and their residents were rendered homeless.

FIRE IN THE DOCKS

Then, at nine o'clock that night, a great fire broke out at a spirits warehouse in the East London Docks.

Firefighters from all over the district raced to the scene, where they had managed to bring the fire under control by soon after midnight.

But, as the exhausted firemen were returning to their stations, the "call" reached them that another even more destructive fire had broken out in the Ratcliff Dry Dock, and they had no choice but to turn around and race back to fight this raging inferno.

Fires often drew crowds of spectators, and many Eastenders headed for the docks to "enjoy" the spectacle, and among them was Emily Holland.

MARY NICHOLS' JOLLY BONNET

Meanwhile, in the Frying Pan Pub, at the junction of Thrawl Street and Brick Lane - a building that still stands, although it is no longer a pub - Mary Nichols finished a drink, and then headed off along Thrawl Street to try and gain admission to Wilmott's. It was later stated that, at this time, she was "the worse for drink, but not drunk."

However, since she didn't have the required fourpence to pay for her bed, she was told by the deputy-keeper that she couldn't stay there, and she was escorted from the premises.

Mary was wearing a bonnet that none of the other residents had seen her with before, and, since she was probably intending to resort to prostitution in order to raise the required lodging house fee, she evidently felt that this would prove irresistible to potential clients. As she left Wilmott's, she turned back to the deputy-keeper, and laughingly told him, "I'll soon get my 'doss' money. See what a jolly bonnet I've got now."

So saying, she headed off into the early morning.

EMILY HOLLAND MEETS MARY

By 2 a.m. the fire in the docks had been all but brought under control, and Emily Holland set off to walk back to Wilmott's.

Heading along Whitechapel Road, she passed St Mary's Church, just as its clock was chiming 2.30 a.m.

Crossing Whitechapel Road, she turned into Osborn Street, where she was confronted by the sight of a drunken Mary Nichols staggering towards her from the direction of Brick Lane.

Mary stopped and, leaning against the shutters of the grocer's shop at the junction of Osborn Street and Whitechapel Road, she boasted to Emily that she had made her lodging money three times over but had spent it.

Concerned at her drunken state, Emily tried to persuade Mary to come back to Wilmott's with her, telling her that she would get her a bed.

Mary refused the offer, but also bemoaned the fact that she had no money, informing Emily that she must make up the amount of her lodging.

Then, confidently predicting that, "it won't be long before I'll be back", Mary staggered off along Whitechapel Road, and Emily set off through Osborn Street to head back to Wilmott's.

That was the last time that anyone, other than her killer, would see Mary Nichols alive.

At some point during the next hour, Mary would meet a man with whom she would go to a secluded gateway, in a nearby dark thoroughfare called Buck's Row, and, by the time she realised the evil of his intent, it would be too late for poor Polly Nichols.