- Emma Elizabeth Smith was attacked by a group of three men in the early hours of the morning of Tuesday, 3rd of April, 1888.

- Although she survived the attack, she later died of her injuries at the London Hospital.

- She told the doctor who treated her that she had been attacked by a group of youths.

- She is not now generally believed to have been a victim of Jack the Ripper, but she was the first name to appear on the Whitechapel murders file.

- Site Author and Publisher Richard Jones

- Richard Jones

EMMA SMITH - ATTACKED 3RD APRIL 1888

THE FIRST WHITECHAPEL MURDERS VICTIM

EASTER HOLIDAY MONDAY

The 2nd of April, 1888, was the Easter bank holiday Monday, albeit the weather that day was not particularly conducive to outdoor pursuits.

As the Glasgow Evening Post put it, on Tuesday, 3rd April, 1888:-

The weather in London yesterday was very unfavorable for holiday making.

Though dull, the morning was dry, and many thousands were tempted abroad in the hope that the rain would hold off.

In this they were disappointed, for at noon heavy rain showers fell, and rendered those in the streets damp and uncomfortable.

As a consequence, all indoor places of resort and amusement became thronged - in some cases to an uncomfortable extent, while the welcome shelter of the taverns appeared to also be taken advantage of to an unusual extent."

EMMA ELIZABETH SMITH

On the Monday evening, at the common lodging house at 18 George Street, Spitalfields, at which she had been a resident for eighteen months, Emma Elizabeth Smith, a 45-year-old-widow, readied herself for a night out.

Emma was what was referred to at the time as an "unfortunate" - one of the lowest classes of prostitutes that plied their trade on the streets, and who conducted their business in any dark corner of any of the squares, balconies, alleyways, passages or even the backyards of the houses of the district.

It was a dangerous business, and Emma - so the deputy keeper of the lodging house, Mary Russell, later recalled - had "often come home with black eyes that men had given her" and had even returned home one night and told her "...that she had been thrown out of a window."

Like many of the "unfortunates" in the East End of London, alcoholism was at the root of Emma's misfortunes. Indeed, Mary Russell would later state that, when she had had a drink, Emma "acted like a mad woman."

WALTER DEW'S RECOLLECTION OF HER

Poignantly recalling her in his memoir, I caught Crippen, fifty or so years later, former East End police officer Walter Dew had this to say about poor Emma Smith:-

Emma, a woman of more than forty, was something of a mystery. Her past was a closed book, even to her most intimate friends.

All that she had ever told anyone about herself was that she was a widow who more than ten years before had left her husband and broken away from all her early associations.

There was something about Emma Smith which suggested that there had been a time when the comforts of life had not been denied her. There was a touch of culture in her speech unusual in her class.

Once, when Emma was asked why she had broken away so completely from her old life, she replied, a little wistfully:- "They would not understand now any more than they understood then. I must live somehow."

So, more lonely even than most of her fellows, she walked the streets of Whitechapel."

SHE SEEMED IN FINE HEALTH

However, when she left 18 George Street on the evening of the bank holiday Monday, Emma was, according to Mary Russell, "apparently in good health."

It was never established what Emma Smith did, or where she went, after she left the lodging house on that Monday evening.

It is probable that, like many Londoners that evening, she spent some of her time drinking in one of the area's many pubs.

SOME ROUGH WORK THAT NIGHT

At a quarter-after midnight on the morning of Tuesday, 3rd April, 1888, Margaret Hayes, a fellow lodger at 18 George Street, saw Emma talking with a man who was wearing dark clothing and who was sporting a white neckerchief.

Margaret Hayes had herself just been assaulted by two men, one of whom had stopped her and asked her for the time, whereupon the other had punched her in the mouth. The two men had then fled into the night.

Later stating that there "had been some rough work that night", Margaret decided to head home and, as she was passing Farrant-street, Burdett Road, she noticed Emma and the man talking together.

She was, so she later testified, certain that the man was not one of the two that had attacked her.

Margaret would also say later that, "the quarter was a fearfully rough one" and that just before Christmas 1887, she had been injured by men under circumstances of a similar nature, and had had to spend a fortnight in the infirmary as a result.

Given her own recent and past experiences, Margaret was not inclined to hang around, and so she continued with her journey and headed back to the lodging house in George Street.

EMMA ARRIVES BACK AT THE LODGING HOUSE

Between four and five o'clock that morning Emma Smith returned to 18 George Street, where Mary Russell became immediately concerned at the state she was in.

"Her face was bleeding," Mary later recalled, "her ear was badly cut, and she said that she was also injured about the lower part of the body."

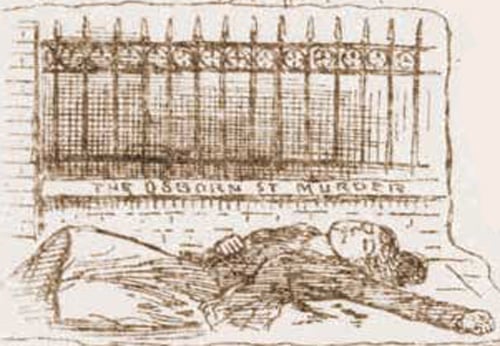

Emma told Mary that she had been "shockingly maltreated by some men" as she was making her way along Osborn Street - the "dirty, narrow entrance to Brick Lane," according to John Henry Mackay, in The Anarchist, written in 1891.

Her assailants, she said, had robbed her of all her money.

Although she could not describe her attackers, she did say that the youngest was aged about nineteen.

A View Along Osborn Street.

THE WALK TO THE HOSPITAL

Mary was extremely concerned about the injuries that her lodger had received and the evident pain and discomfort she was obviously in, and she tried to persuade Emma to go with her to the nearby London Hospital. However, Emma was reluctant to do so.

Mary persevered, and Emma finally gave in and, accompanied by fellow lodgers Margaret Hayes and Annie Lee, they set off for the fifteen or so minute walk to the nearby London Hospital on Whitechapel Road.

As they passed along Osborn Street, Emma pointed to a spot near Taylor's cocoa factory and stated that that was the location where the outrage against her had been perpetrated.

SEEN BY THE DOCTOR

On arrival at the London Hospital, Emma Smith was seen by Dr. George Haslip, the House Surgeon.

He later testified that, although she had probably been drinking, she was not intoxicated, and she "knew what she was about."

On examining her, he found that the injuries that she had suffered were truly horrific.

A portion of the right ear was torn, and the peritoneum and other internal organs had been ruptured, which, he later stated, led him to believe that the injuries had been caused by some blunt instrument having been thrust into her with very great force.

He asked her how she had come by the injuries, to which she replied that she had been walking past Whitechapel church at about half past one on Tuesday morning, when she saw some men approaching.

She had crossed over the road to avoid them, but they had proceeded to follow her along Osborn Street, where they assaulted her, robbed her of all the money she had, and then committed the outrage.

There were, she told the doctor, two or three men, one of them looking like a youth of about 19.

She was, Haslip later stated, somewhat reticent with regard to the details, but she distinctly denied having addressed the men in solicitation.

She could not tell whether it was a knife or what instrument it was that had been used on her.

She also told him that she was originally from the country, but that she had not seen her friends or family for ten years.

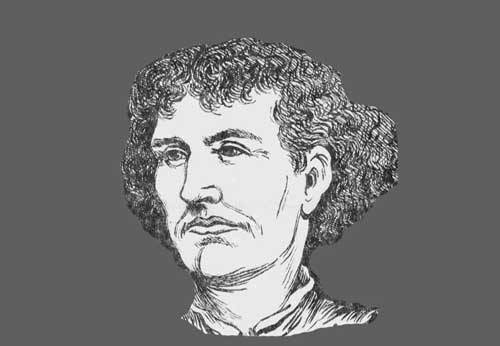

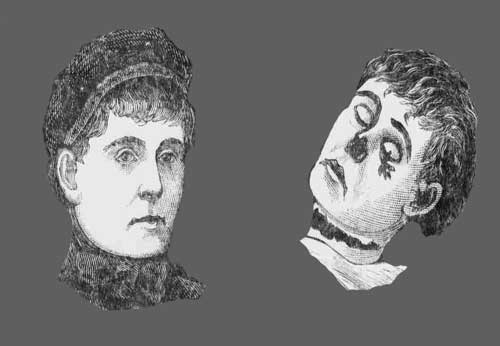

Emma Smith Following The Attack

From The Illustrated Police News.

Publication date: Saturday, 10th October, 1888

Copyright. The British Library Board.

HER DEATH

Emma's injuries proved to be extremely serious, and it wasn't long before peritonitis had set in, and, having sunk into a coma, she died at nine o'clock on the morning of Wednesday, 4th April, 1888.

INSPECTOR REID'S REPORT

Inspector Edmund Reid, head of the Criminal Investigation Department (CID) of the Metropolitan Police's H Division, prepared the following report on the case:-

Emma Elizabeth Smith, 18 George Street, Spitalfields. Son and daughter living in Finsbury Park area. She had lodged at the above address for about eighteen months, paying 4d. per night for her bed.

She was in the habit of leaving at about 6 or 7 p.m. and returning at all hours, usually drunk.

On the night of 2nd April, 1888, she was seen talking to a man who was dressed in dark clothes and who was wearing a white scarf, at 12.15 a.m. [on the 3rd.] She returned to her lodgings between 4 and 5 a.m. She had been assaulted and robbed in Osborne Street.(near Cocoa factory) Messrs. Taylor Bros.

At London Hospital, she was attended to by Mr. George Haslip, House Surgeon. She died at 9 a.m. on the 4th. The inquest was held by coroner Wynne Baxter at the Hospital.

The first the police knew of this attack was from the Coroner's Officer who reported in the usual manner on the 6th inst. that the inquest would be held on the 7th inst. Chief Inspector West attended.

None of the Pc's in the area had heard or seen anything at all, and the streets were said to be quiet at the time.

The offence had been committed on the pathway opposite No. 10 Brick Lane, about 300 yards from 18 George Street, and half a mile from the London Hospital to which deceased walked. She would have passed a number of Pc's en route but none was informed of the incident or asked to render assistance.

The peritoneum had been penetrated by a blunt instrument thrust up the woman's passage, and peritonitis set in which caused death.

She was aged 45 years, 5' 2'' high, complexion fair, hair light brown, scar on right temple. No description of men.

Edmund Reid Inspr."

CHIEF INSPECTOR WEST'S ADDITIONAL REPORT

Reid's superior officer, Chief Inspector West, attended the inquest into Emma Smith's death on behalf of the police and he was reported to have told the Coroner that "..he had made enquiries of all the constables on duty on the night of 2nd and 3rd April in the Whitechapel Road..."

In a subsequent report West stated that:-

...Coroner further expressed his intention of forwarding the particulars of the case to the Public Prosecutor as being one requiring further investigation with respect of the person or persons who committed the crime.

Witnesses stated that they did not think it necessary to report the circumstances to the police. Whole of police on duty deny all knowledge of the occurrence.

Inspector west.

Enquiry to be taken up by Inspector Reid."

NEWSPAPER REACTIONS

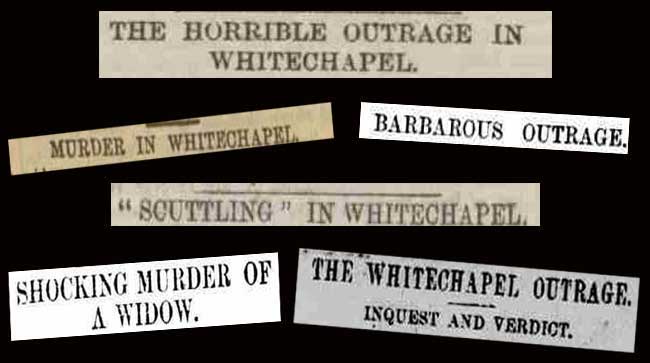

It is often stated that the newspapers paid little heed to the fate of Emma Smith. This is simply not true. Indeed, newspapers across the country reported the case. "Horrible Murder In Whitechapel"; "Murder By Whitechapel Roughs"; "Brutal Murder In Whitechapel - Foul Haunts To Cope With"; "Barbarously Murdered", were just some of the headlines that appeared in the press over the days that followed the murder.

Newspaper headlines Concerning The Murder Of Emma Smith.

A HIDEOUSLY SORDID STORY

The Worcestershire Chronicle, on Saturday, 14th April, 1888, looked back on what was seen as the tragedy of the depths of degradation to which Emma Elizabeth Smith, and to which hundreds like her in the district where her murder had occurred, had sunk:-

"Seldom, writes a lady in a London contemporary, has a more hideously sordid story of a woman's career been unrolled than was that of Emma Smith.

Robbed, outraged, and wounded unto death, under circumstances of exceptional brutality, by a gang of ruffians while she was staggering "home" the worse for drink down a bye-street between Whitechapel and Spitalfields after a Bank Holiday "spree,", it was a terrible end to a terrible life.

The "home" was a common fourpenny lodging house.

She had not corresponded with, nor seen a relation for ten years.

It seems scarcely possible to believe that a woman could fall to such depths of degradation, and yet she is no more than a typical example of those who patronize the foul haunts of these fearful houses, where drinking, fighting, and all other loathsome vices are the pastime of the poor wretches who can raise two shillings a week for the "accommodation" they get within their foetid walls.

A woman's mission to these houses would have awful scope of sin and misery to cope with.

Are there no brave and pure souls who could take up such a work?"

BARBAROUSLY MURDERED

The inquest into her death was held at the London Hospital on Saturday, 7th April, 1888.

Few people could disagree with the the Coroner, Mr. Wynne Edwin Baxter when, during his summing up, he decreed that the woman had been "barbarously murdered" and opined that it was "impossible to imagine a more brutal and dastardly assault,"

The jury willingly followed his suggestion that they should bring in an immediate verdict of "Wilful murder against some person or persons unknown."

THE START OF THE WHITECHAPEL MURDERS

Emma Smith probably wasn’t a victim of Jack the Ripper. Indeed, the fact that she was able to tell the attending doctor that she had been attacked by a group of men, suggests that she was attacked by one of the local gangs that preyed on the district's prostitutes.

This was evidently the conclusion that the police came to at the time, and this belief would influence their line of enquiry in the early days of the hunt for Jack the Ripper.

But, the death of Emma Smith was significant in one major respect. It was with her killing that the police opened a file which they titled "The Whitechapel Murder"; and, by the end of that year, that file had become the "Whitechapel Murders" file, and would contain the names of the five "canonical" victims of Jack the Ripper.

And Emma Smith, although not a victim of Jack the Ripper, is the first victim to appear in the generic Whitechapel Murders file.

Article Sources

Sheffield Evening Telegraph 5th April 1888

York Herald 6th April 1888

Lloyd's Weekly Newspaper 8th April, 1888