- Sir Charles Warren was the Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police from 1886 to 1888..

- Warren's tenure was marked by frequent clashes between him and the Home Secretary, Sir Henry Matthews.

- In November 1887 his heavy-handed put down of a protest meeting in Trafalgar Square led to his becoming a pariah in the eyes of the radical press.

- When the Jack the Ripper murders exposed the shortcomings of the police certain of, these newspapers took the opportunity to attack Warren on an almost daily basis.

- In November, 1888, following a disagreement with the Home Secretary, Warren resigned.

- Site Author and Publisher Richard Jones

- Richard Jones

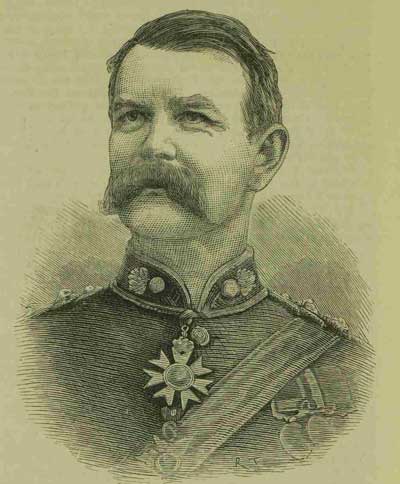

SIR CHARLES WARREN

METROPOLITAN POLICE COMMISSIONER 1886 - 1888

Sir Charles Warren was appointed the Chief Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police in March 1886, and his appointment met with universal approval.

A renowned military man, not to mention a distinguished archaeologist and cartographer, Warren took up office with high hopes of bringing much needed discipline to the Metropolitan Police, and he does appear to have won the respect and loyalty of most of the rank and file officers, albeit it has been commented that the constabulary as a whole found him somewhat aloof.

Ultimately, his term as Commissioner would prove to be an extremely stormy one, marked by several PR disasters, such as "Bloody Sunday", in November, 1887 - which turned many newspapers against him - and his force's inability to solve the Jack the Ripper murders of 1888.

In the century and more since the murders occurred, Warren has been subjected to a barrage of, largely undeserved, criticism and ridicule, most of which is based on several misconceptions and outright inaccuracies about his handling of the case

JUST THE MAN FOR THE JOB

But, in 1886, he was seen as just the man for the job and The Times viewed his appointment with "much satisfaction" and assured its readers that:-

...he has earned his promotion, and we have every confidence that he will show himself deserving of the high trust which has been committed to him. It seems, indeed, as if Sir Charles Warren were one of our indispensable men...In no safer hands could the promised reorganisation of the London police be placed. We may look to him, as a military man, for the control and discipline of the important force which he will command..."

The Times went on to applauded him as being:-

...precisely the man whom sensible Londoners would have chosen to preside over the Police Force of the Metropolis...there are few officials...who have had more varied experience. He is at once a man of science and a man of action..."

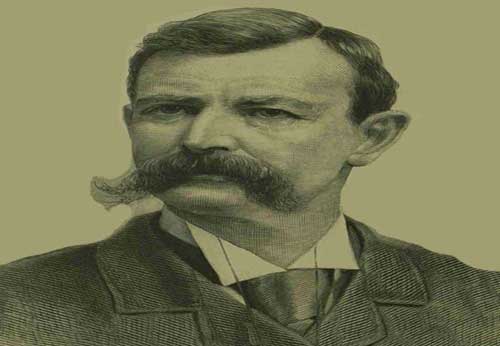

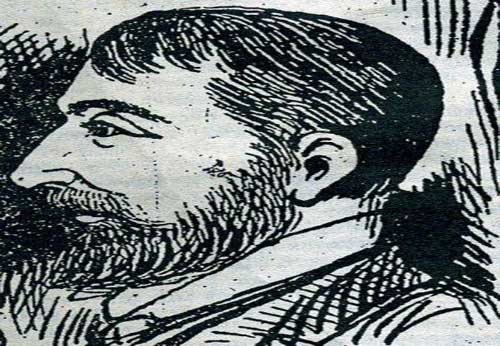

Sir Charles Warren

1886

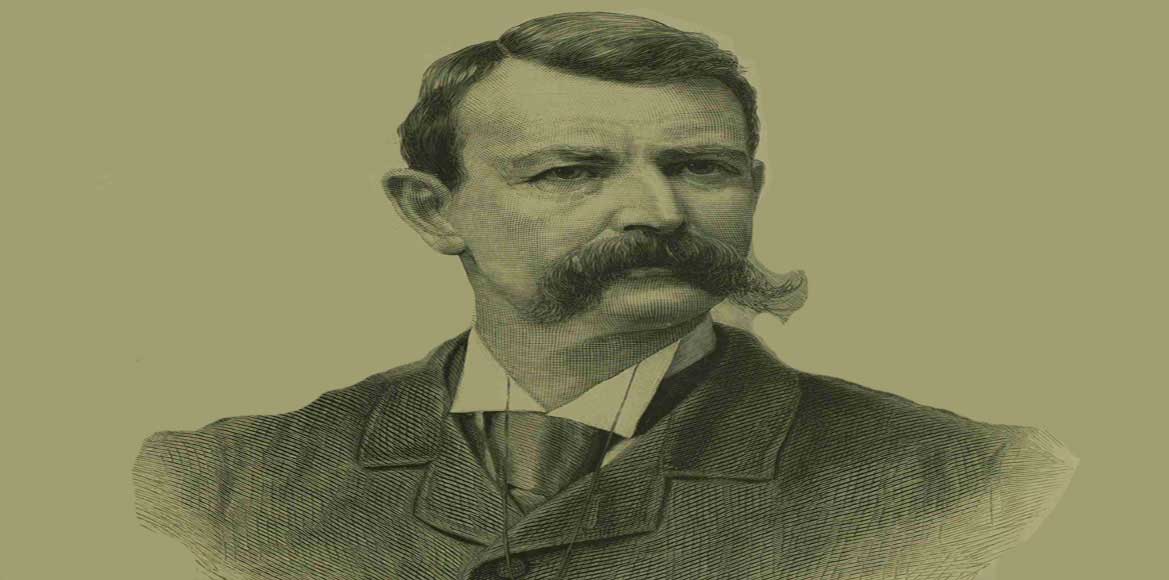

Major General Sir Charles Warren

1884

As for what Sir Charles Warren was like as a person, several newspaper's commented on his military bearing and no-nonsense attitude.

As one commentator put it "he is the iron fist without the velvet glove".

The Fife Free Press, had this to say about him:-

At first thought, one can scarcely imagine so daring a soldier to be the right man in the right place in the circumscribed sphere of a policeman's life, even though the appointment he is holding is that of chief at Scotland Yard.

But, much as Sir Charles is missed, and will be missed from the special service wing of the army, he has many qualifications which fit him for the most responsible constabulary appointment in the world.

He is a man of iron determination, a tried and able administrator, a capital organiser, and essentially a leader of men.

Without being a martinette, he is an officer whose men will always fear him so much as to make them alert in their duty. He is blunt and dogged, and yet sympathetic with those who devote themselves intelligently and assiduously to their posts.

Somebody once called Sir Charles Warren a "belated Ironside", because of his Puritan honesty of sentiment and strong religious character. With his sterling worth and high ideal of duty, he is not, however, by any means lacking in tact.

Personally, Sir Charles is of a soldierly bearing and bronzed, with a somewhat fierce appearance, but he is of quiet and unobtrusive manners, and socially a thorough gentleman.

He is, what is, perhaps, remarkable in such a man, a keen lover of painting and poetry, and he is a staunch believer in the potency of water-drinking."

A PROPHETIC WARNING

The only real concern about Warren's appointment - and, as it transpired, a somewhat prophetic one - was whether, as a man of action, more used to giving orders than taking them, he would be able to assume the role of a subordinate to his direct superior, the Home Secretary.

Indeed, several newspapers commented on his being "impatient of authority", and pondered whether this would bring him into conflict with the Home Office, the head of which, at the time of his appointment, was Home Secretary Hugh Childers.

In an editorial, published on 20th March, 1886, The Graphic wondered how Warren would fare at taking orders from the Home Office:-

SIR CHARLES WARREN. It is so like our English way of doing things. Just when Sir Charles Warren has mastered the complexities of the situation at Suakim, and has conceived a plan, as he asserts, by which the adjacent country might be opened out to trade and pacified, we recall him to take charge of the Metropolitan Police.

No doubt he is a very good man for the purpose; firm, considerate, sagacious, and capable... He possesses, too, the rarer merit of adaptability to circumstances, while his public record is unblemished by a single failure.

All the same, his recall brings back to memory the abortive Suakim Railway, which was hardly begun when the edict went forth for its abandonment.

Fortunately, the country is not put to any fruitless expense in the present instance, while it is an additional consolation to remember that the life of this valuable public servant will not be endangered by passing the summer on the pestilential littoral of the Red Sea.

Nor will the new Chief Commissioner find our Hyndmans and Champions such tough customers as Osman Digma.

His chief source of trouble is more likely to be the supremacy of the Home Office over Scotland Yard. He bears the reputation of liking to have his own way, and, if report speaks truly, that was a weakness which a former Home Secretary could not tolerate for a moment.

It will be remembered that Sir Charles Warren showed himself somewhat impatient of authority when, lately employed in South Africa, his controversy with Sir Hercules Robinson being marked, at one time, by a distinct disposition to kick over the traces.

It is to be hoped, therefore, for the peace and comfort of all concerned, that Mr. Childers will leave the Chief Commissioner severely alone.

Hercules Robinson

(1840-1927)

Hugh Culling Eardley Childers

(1827 - 1896)

THE NEXT POLICE REGULATION

Warren's reputation for "hands-on" leadership was commented on by The Leigh Chronicle in its "Wit and Humour" section on Friday 23rd April, 1886:-

Another soldier has been appointed to command the Metropolitan Police. It is reported that Sir Charles Warren must see to everything himself.

Bewildered Detective: Pickpocket! What does the book say? (Takes out Policeman's pocket-book.) P—P—P, Oh, here it is: "Tell nearest constable, who will tell sergeant, who will tell inspector, who will tell superintendent, who will tell Sir Charles Warren who will come and take pickpocket into custody."

NEW POLICE DIVISIONS

Sir Charles Warren formally took over the Chief Commissionership of the Metropolitan police on Thursday, April 1st, 1888.

One of the first reforms to be made during his tenure was the reorganisation of several divisions of the Metropolitan Police.

This led to the creation of two new divisions, F and J. Significantly, from the perspective of the Whitechapel murders, it would be in the area covered by J Division that the first Jack the Ripper murder, that of Mary Nichols, would take place on 31st August 1888.

The Illustrated London News took a look at these new divisions in an article published on Saturday, April 10th, 1886:-

Sir Charles Warren, the new Metropolitan Police Commissioner, who arrived in London on Monday week, has begun work.

On the 1st inst., being the commencement of the financial year, several important alterations which have been made in the composition of the police force came into effect.

In consequence of the continued growth of the Metropolitan Police from year to year since the various divisions were last arranged, great inequalities have for some time existed in their strength, and the extent of ground which they covered.

Nearly every division north of the Thames has, however, been remodelled, and two new divisions have been created, which are to be known by the letters F and J.

The F division comprises the districts of Paddington, Notting-hill, and Kensington, and is formed out of portions of the X and T divisions; the J division will comprise Bethnal-green and its neighbourhood, and is formed out of small portions of the K, H, G, N, and Y divisions.

It is expected that other divisions will shortly be formed, and that extensive alterations will also be made in the south of London.

A NEW POLICE HEADQUARTERS

At the time of Warren's appointment the Metropolitan police were headquartered at 4 Whitehall Place, a location they had occupied since the force was founded in 1829.

Over the years, as the force had expanded, different departments had been established in a variety of buildings around Whitehall Place, a situation that wasn't ideal for efficient communication between the various sections.

In the month that Warren's Commissionership began, it was announced that a substantial sum had been allocated towards the building of a new Central Police Station which, in the words of The Glasgow Evening Post w. would provide, "...the necessary offices, houses and accommodation worthy of the metropolis and of the importance of the force whose headquarters it will form..." Sir Charles Warren, so the article continued,"...is devoting his earnest attention to the scheme, and directly the Home Secretary has obtained parliamentary sanction, the matter will be pushed forward without delay."

Ultimately, the new headquarters would emerge on the Victoria Embankment, and would become New Scotland Yard, a building that would be the Metropolitan Police headquarters from 1890 to 1967.

However, not everybody was convinced that spending such a substantial amount on a new headquarters for Warren's force was going to be money well spent, as is evidenced by the following article, which appeared in The Ross Gazette on 29th April, 1886:-

Sir Charles Warren has lost no time in commencing the work of reorganising the police force.

He has decided upon the necessity of erecting a central police station, which is to be the headquarters of the Metropolitan Constabulary.

Two hundred thousand pounds is spoken of as the sum which will be expended on the site and building, and already inquiries are being made about a suitable site.

Other things are more urgently required than an outlay upon bricks and mortar, and it is to be hoped that the new Commissioner will not feel satisfied by introducing a little more exterior impressiveness and a little more military precision.

No doubt Scotland Yard is deficient in its arrangement and accommodation, and defective offices, both in public and private business, often produce defective work.

Probably Sir Charles is right; In another way, externals have a great effect upon employees. The whole police system at present stands impressed with the hole and corner character of Scotland Yard."

RABIES AND DOG MUZZLING

It wasn't long into his tenure that Warren found himself confronting a conundrum that had been concerning the police for some time - the vexed question of rabies and dog muzzling.

Warren, showed himself to more than up to the task of tackling the issue and, in May 1886, he issued an order that all dogs on the streets of the Metropolis that were not on a lead or properly muzzled, would be considered as not under proper control, even if the dog was close to and following its owner. The owners of any such dogs would be issued with a police summons for allowing a dog to be at large, contrary to the order of the Commissioner of Police.

In fairness to Warren, the problem of unmuzzled "mad dogs" - and the danger of rabies that was posed by them - on the streets of London was a serious one, and many newspapers gave him their whole-hearted support in his stance.

However, many London dog owners simply ignored the edict and so, on Wednesday June 16th, 1886, Warren issued a further order stating that, "...for the next three months, in the Metropolitan Police district, any dog not under "proper control" in a public place, or place used by the public, will be seized by the police."

But, as The Kentish Mercury pointed out, on Friday 18th June, 1886:- "Nothing is said in the new order about dogs being muzzled or led."

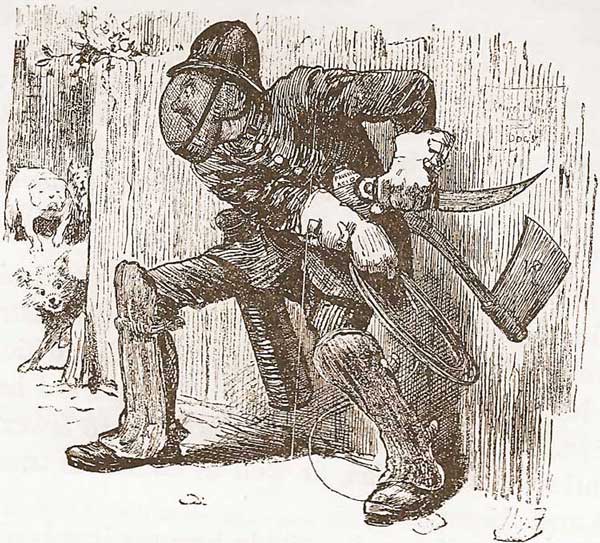

THE DOG SCARE

The Policeman As He Ought To be (Properly Protected)

Outside The Six Mile Metropolitan Radius.

Punch, November 6th, 1886

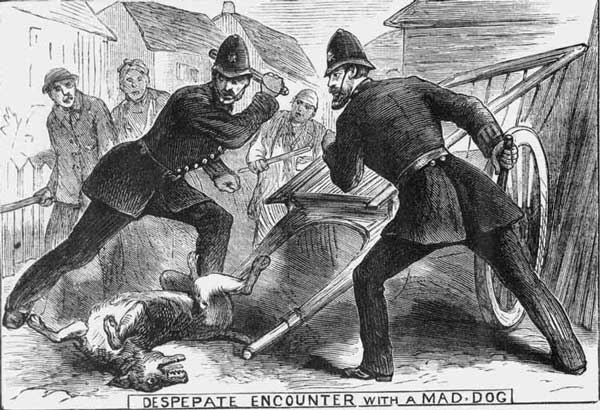

A DOG BEATEN TO DEATH

The press had a field day with Warren's war on London's canine population, and numerous cartoons and articles were soon making mirth of his tough stance, with many going so far as to observe that his men could, to say the least, be a little over zealous in enforcing their Chief's order.

In early July, George Sims, writing in his Dagonet column in Referee highlighted a case in which a dog had been beaten to death on the streets of London by, seemingly, over-zealous police officers:-

The story of the policeman who beat out the brains of a muzzled dog on a doorstep in Baker Street does not read prettily. The dog had just been let out, and there is not the slightest reason to believe that there was anything the matter with him. I can quite understand and sympathize with the feelings of the lady who resented the cruel butchery being carried out upon her premises.

The force of foolery can no further go than this.

A muzzled dog, a harmless pet, runs out of its owner's front door for a moment, and is instantly seized and beaten to death by a posse of policemen under the command of an inspector!

Pasteur has much to answer for.

It is becoming every day more and more patent that this panic is being fostered in the interests of vivisection. Hundreds of cases of of hydrophobia are deliberately manufactured in order to keep down the opposition to the cutting up of living animals.

But even vivisection as conducted by Pasteurites pales its ineffectual fires before the vivisection of tame muzzled dogs as carried out by the police upon doorsteps. Doorsteps are not licensed for the purpose at present, and Sir Charles Warren might remind his young men of the fact."

The Illustrated Police News, July 17th, 1886

A WAR OF WORDS

What the press were dubbing "The London Dog Hunt" was the first time in his tenure that the new Commissioner faced open hostility from the newspapers - albeit it would, most certainly, not be the last.

Warren didn't help matters by actively engaging with those he perceived as being unfairly critical of his tough stance, amongst them Mr Colam, the Secretary of the Dogs' Home at Battersea.

In their annual report the Dogs' Home Committee had seen fit to publish some "strong remarks" relative to the number of dogs that had been destroyed by the police.

Affronted, Warren had hit back with an open letter in which he pointed out that, whereas only 300 dogs had been killed by the police during the year, more than 20,000 had been put to death in the Dogs Home - or, to put it another way only one in every five dogs sent to the Home was restored to its owner." Sir Charles, therefore, complains that the report does not do justice to the work of the police...", observed The Globe, on Friday, 2nd July, 1886.

Warren would have been better advised to have left well alone in this particular dog fight.

Several newspapers took up the cudgels on behalf of the Dogs' Home, and pointed out that Warren had completely missed the point.

The Globe pointed out the misconception that Warren was labouring under:-

Sir Charles has mistaken, we should imagine, the real cause of complaint. The report does not complain of the number of dogs that have been destroyed by the police, but rather of the mode of destruction.

The system employed in the Dogs' Home itself is so absolutely painless that we can well understand the feelings with which the committee must regard the cruel and clumsy methods employed by the police.

To watch a poor unfortunate animal, suspected of rabies, being beaten to death by the truncheons of two or three constables, is a sickening sight, and, if 300 dogs were destroyed by the police, a good many must have suffered tortures compared to which the death of 20,000 dogs in the lethal chamber is nothing..."

A NEW HOME SECRETARY

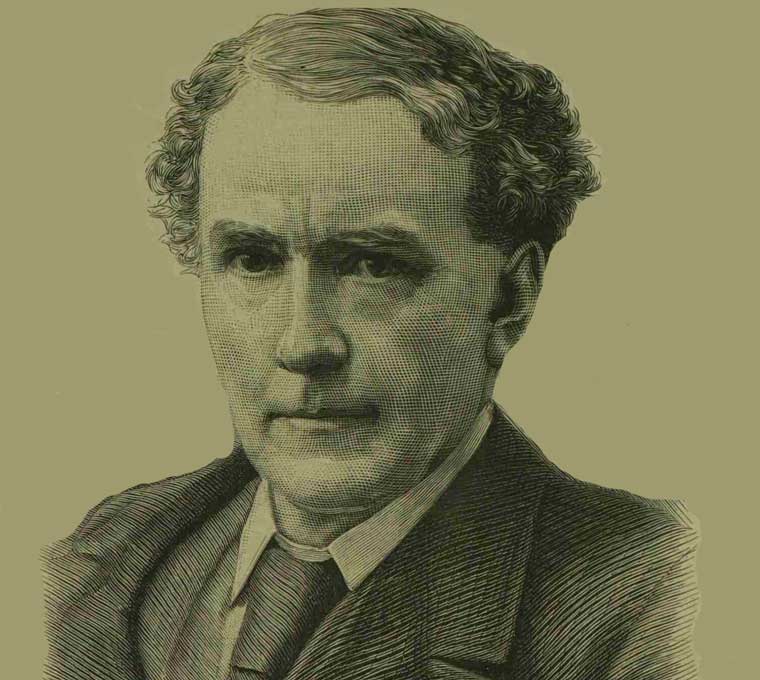

Warren appears to have enjoyed a cordial working relationship with the Home Secretary at the time of his appointment, Hugh Childers, and, it must be said, Childers seems to have been happy to let Warren get on with his job without too much interference.

However, in early August, 1886, a change of government saw the appointment of a new Home Secretary, Henry Matthews.

Warren and Matthews were, very much, political opposites - Warren being distinctly radical and liberal in his outlook, whereas Matthews, a devote Roman Catholic and confirmed bachelor, had renounced his original, self-professed, stance of "Independent Liberal and Conservative", in favour of staunch Conservatism.

The stage was set for confrontation between the Police Commissioner and the Home Secretary, and, over the next two years, they would clash constantly, both privately and in public.

Indeed, several of the decisions that Warren found himself pilloried for by the press, were in, fact, decisions made by either Sir Henry Matthews or his underlings at the Home Office.

Sir Henry Matthews

(1826 - 1913)

BURGLARS AT LIBERTY

By September, 1886, the fact that Sir Charles had devoted so much of his force's energies to the "dog hunt" in London, had led to press accusations that other crimes, such as burglary, were not receiving the attention they deserved on account of the Chief Commissioners apparent dog obsession.

George Sims, in his Dagonet column in The Referee chided the police with the following apocryphal story:-

I met a burglar the other day whom I have known for years. I asked him how business was, and he replied "Excellent;" that they were never noticed by the police now, and that burglary was as easy as pocket-picking.

"You see, sir," he said, when we goes a burglin' now we takes a dawg or two. Directly we gets to the job we turns the dawgs loose, and they're trained to run away. Not bein' muzzled, oft the police goes after 'em, and the dawgs gives 'em a good run, and takes 'em right off our pitch, and when the police is arter the dawgs we does our business. Lor', sir, since Sir Charles Warren got the dawg craze into his head burglars and thieves in general have had a real good time. The force don't pay any attention to us. Their energies is all directed to pleasing the chief by stealing the taxpayers' dawgs."

DRINKING ON DUTY

In 1887, Warren began instituting various reforms aimed at bringing what he saw as much needed discipline to the force.

The Entr'acte, in an editorial on Saturday, 14th May, 1887, took issue with his firm stance on drunkenness on duty amongst the uniformed police officers:-

Sir Charles Warren is a man with an iron hand, and in the "force" he is getting himself disliked.

Being himself a staunch teetotaller, to say nothing of his psalm-smiting proclivities, he holds no sympathy with those constables who are not yet convinced that water is the only liquid that a policeman should consume.

Sir Edmund Henderson was an easy-going chief, and, I believe, was never known to discharge or reduce a constable for the first offence of being under the influence of drink.

Sir Charles Warren holds entirely different views, and is very severe on officers who have, even for the first time, been reported as having taken a "drop too much."

...No doubt Sir Charles Warren works with the best motives, but it is quite possible that if he makes his line so hard and fast, he will drive from active service valuable men, and thus bring a hornet's nest about his ears that will push him from office within the next twelve months.

Policemen are not sent down from heaven pure, undefiled, and temptation-proof; they have their little weaknesses, like other people, and the chief who refuses to tolerate them because they don't happen to reach his ideal will presently find that he will not be able to get labourers to work in his vineyard.

There are abuses in our police system which should have been purged away years ago; at the same time it must be borne in mind that the force contains a host of honest and capable men who, rather than stay and be throttled by a chief who insists on pulling the string too tightly, will retire at the earliest opportunity.

In speaking of the police, I refer to the uniform men, and not to the plain-clothes officers, whose ways are, perhaps, a little bit more mysterious."

BLOODY SUNDAY - NOVEMBER 1887

Warren's reputation as a man of action was put to the test on 13th November 1887, a day that became known as "Bloody Sunday."

During the summer of 1887 large numbers of destitute unemployed had begun camping out in Trafalgar Square and using it as a meeting place.

As a result the Square had become a hotbed of political agitation, and Warren, fearing that this growing disquiet might soon place London at the mercy of the mob, requested that the Home Secretary, Henry Matthews, ban all meetings in Trafalgar Square.

Matthews prevaricated for almost two months, forcing Warren to send 2,000 policemen into the Square at weekends to maintain public order.

MATTHEWS FINALLY DECIDES

In early November Matthews finally made a decision, and Warren was authorised to veto further meeting in the Square.

Up until that point the left wing press had looked upon Warren as an intellectual progressive and had afforded him a reasonable amount of respect.

But they now saw the ban as having been done at his sole discretion and, feeling it to be unlawful, the Metropolitan Radical Association decided to challenge it by calling a meeting in the Square for 2.30pm on Sunday 13th November.

Warren stuck to his guns and expressly forbade any procession from entering the Square at the appointed time.

LOOMING CONFRONTATION

The stage was set for confrontation and, according to newspaper reports, 20,000 protestors (the police estimated twice that number, the organisers half) converged on the Square, where Warren had stationed 2,000 constables, two deep in a ring around its interior.

A further 3,000 were kept in readiness, and a battalion of Grenadier Guard foot soldiers, plus a regiment of mounted Life Guards were kept on standby.

The three leaders of the Social Democratic Federation, Hyndman, Burns and Cunninghame Graham, linked arms and vowed to breach the circle.

Hyndman found himself lost in the crowd, but the other two made it to the police line where they exchanged blows with the officers and were duly arrested and locked up

EYE WITNESS ACCOUNTS

An idea of the brutality of what was to come can be gleaned from an eye witness account of the arrest of Cunninghame Grahame, Radical-socialist MP for Lanark:-

After Mr. Grahame's arrest was complete one policeman after another, two certainly, but I think no more, stepped up from behind and struck him on the head from behind with a violence and brutality which were shocking to behold. Even after this, and when some five or six other police were dragging him into the square, another from behind seized him most needlessly by the hair... and dragged his head back, and in that condition he was forced many yards

THE MOOD CHANGES

Suddenly, the mood of the crowd, which up until that moment had been good humoured, changed.

Warren called for re-enforcements and 400 foot soldiers and mounted police divisions together with the Life Guards and Grenadier Guards were deployed to disperse the crowd.

Socialist poet, Edward Carpenter was in the Square and witnessed the carnage that followed:-

The order had gone forth that we were to be kept moving. To keep a crowd moving is, I believe, a technical term for the process of riding roughshod in all directions, scattering, frightening and batoning the people..

Socialist artist Walter Crane, who was also present, commented that:-

I never saw anything more like real warfare in my life - only the attack was all on one side. The police, in spite of their numbers, apparently thought they could not cope with the crowd. They had certainly exasperated them, and could not disperse them, as after every charge - and some of these drove the people right against the shutters in the shops in the Strand - they returned again.

POLICE BRUTALITY

As the melee ended, two protestors lay dead, a hundred people had been hospitalized, 77 constables had been injured, and 40 protestors had been arrested.

By the end of the week, seventy five charges of brutality had been lodged against the police.

PRAISE AND CRITICISM FOR WARREN

But, as far as the authorities were concerned, Warren was the hero who had made a decisive stands against both the mob and the threat posed to public order by socialism.

The Times was fulsome in its praise and commented how Warren's decisive action had undermined "a deliberate attempt...to terrorize London by placing the control of the streets in the hands of the criminal classes."

To the radicals, however, he had become an autocrat, and from that point on they sought any opportunity to attack and undermine him.

Consequently when the Jack the Ripper murders occurred and the police appeared unable to catch the killer, the radical press saw an opportunity to avenge itself on Warren, and he would find himself vilified in many newspapers for his mishandling of the investigation.

Article Sources

Sheffield and Rotherham Independent Saturday, November 21, 1885.

The Globe Saturday, March 13, 1886.

The Graphic Saturday, March 20, 1886.

The Illustrated London News Saturday, April 10, 1886.

Leigh Chronicle and Weekly District Advertiser Friday, April 23, 1886

The Ross Gazette Thursday, April 29, 1886.

The Illustrated London News Saturday, May 1, 1886.

The Fife Free Press Saturday, July 31, 1886.

The Entr'acte Saturday, May 14, 1887.

Copyright Acknowledgements

The Images of Major General Sir Charles Warren, Hercules Robinson, Hugh Culling Eardley Childers and Sir Henry Matthews used on this page are the copyright of

The Illustrated London News Group/Mary Evans Picture Library, all rights reserved.

The Images Sir Charles Warren, the Dog Scare, and those from the Illustrated Police News are the copyright of The British Library Board, all rights reserved.