- Sir Henry Matthews was Home Secretary from 1886 to 1892, a period that saw the occurrence of all the Whitechapel murders.

- Renowned as a skilled orator, Matthews appointment was, nonetheless, met with a degree of surprise by the newspapers.

- Over the next two years he found himself constantly at loggerheads with various elements of the press and there were frequent calls for his resignation.

- Matthews also clashed frequently with the Chief Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, Sir Charles Warren.

- Site Author and Publisher Richard Jones

- Richard Jones

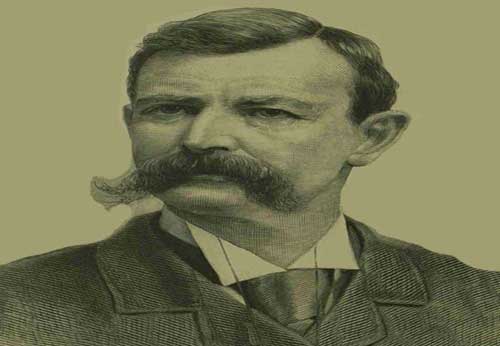

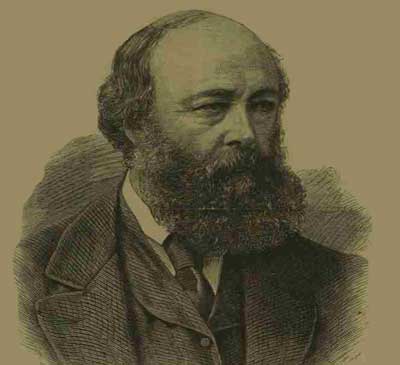

SIR HENRY MATTHEWS

HOME SECRETARY 1886 - 1892

Sir Henry Matthews (1826 - 1913) became Home Secretary in July, 1886, as part of Lord Salisbury's Government. There was one thing that many newspapers agreed upon concerning his appointment, and that was, that it was, to say the least, a "surprise" appointment.

For one thing, he had been out of mainstream politics for over twelve years, and had relatively little political experience.

For another, Henry Matthews was a staunch Roman Catholic and, as such, held the distinction of being the first Roman Catholic to be appointed to the cabinet since the reign of Queen Elizabeth 1st, almost three hundred years before.

EDUCATED IN PARIS AND LONDON

His Catholicism had debarred him from entering either Oxford or Cambridge Universities and, as a consequence, he had been educated at the Sorbonne in Paris, followed by a stint at London University, from which he graduated in 1849 with a Bachelor of Laws (LLB).

Called to the Bar, by Lincoln's Inn, in 1850, he went on to build a solid reputation as a formidable barrister, and demonstrated great flair as a pleader and arguer on the Oxford Circuit, where his distinctly continental oratorical style, influenced by his time in Paris, led to him being dubbed, "The French dancing master."

HIS FIRST FORAY INTO POLICITCS

He first entered Parliament in 1864, as the Member for Dungarven, in Ireland; but, on losing his seat in 1874, he returned to practicing law and, although he stood in several elections, he would remain out of Parliament until 1886, in which year he changed his political allegiance to Lord Salisbury's Conservative party, and, in July, 1886, he succeeded in winning the Birmingham East seat and was returned to Parliament in July 1886.

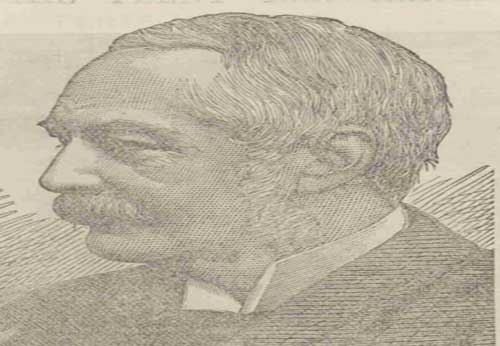

A protégé of Lord Randolph Churchill (1849 - 1895), who became Chancellor of the Exchequer in the new Cabinet, Henry Matthews was, according to a rumour repeated by several newspapers, appointed at the personal insistence of Queen Victoria, who had, reputedly, been extremely impressed with the way he had cross-examined Sir Charles Wentworth Dilke in the witness box during the Crawford divorce case.

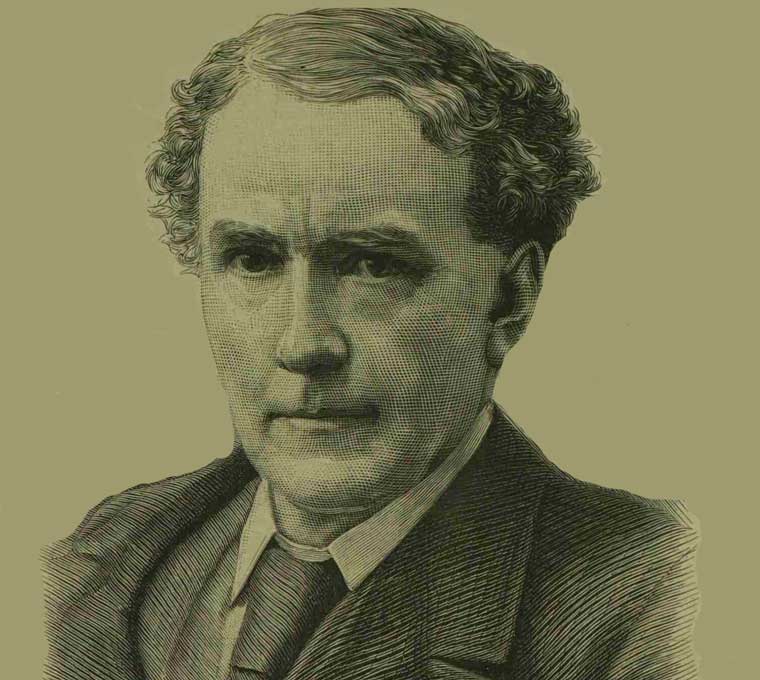

The Marquis of Salisbury

1885

Lord Randolph Churchill

1886

A FORCIBLE AND IMPRESSIVE SPEAKER

The Times, in reviewing the new appointments in the Government, in its edition of 30th July, 1886, observed that:-

...undoubtedly the most interesting and the most unexpected of Lord Salisbury's appointments is that of Mr. Henry Matthews as Home Secretary.

Mr. Matthews is a distinguished leader at the Bar, as a recent cause célébre in which he was a protagonist, has reminded the public, but he may be said to be new to Parliamentary life, having only been elected the other day for one of the divisions of Birmingham, the first Conservative returned for that great borough since its enfranchisement.

It is true that many years ago Mr. Matthews sat as M.P. for Dungarven lit the Parliament of 1868, when he was elected as a 'Liberal Conservative'. Though an Englishman, he was a Roman Catholic, and his creed, which stood in his way in England, constituted his principal claim on the Irish electors.

A forcible and impressive speaker, he nevertheless failed to make any great mark at that time in the House of Commons.

Now he has suddenly leaped to the Treasury Bench, and has grasped one of the great prizes of politics before he has taken his seat as member for Birmingham.

The nomination is, evidently, an experiment, for Mr. Matthews is a 'dark horse.'

It may be presumed, however, that Lord Salisbury, in taking a step so unusual, has not acted at random.

A strong Home Secretary, though his office does not afford much opportunity for display, would be a pillar of the Administration, and if Mr. Matthews does not turn out to be a Minister with vigour and backbone as well as a powerful debater, a mistake will have been made which there are no reasons for anticipating."

SURPRISING, EVEN TO HIS FRIENDS

The Evening Standard, in its edition of 30th July, 1886, was another newspaper that expressed surprise at his appointment:-

...The nomination which will excite most interest is unquestionably that of Mr. Henry Matthews to the post of Home Secretary.

Mr. Matthews has for some years been a distinguished member of the Bar, and his name has naturally occurred to the minds of most people when the probable nominations to the law officerships have been discussed.

But it will be a surprise, even to his friends, to find that at a bound he has stepped from the position of a successful lawyer and a successful candidate for Parliamentary honours to one of the most responsible and conspicuous positions in the State...We do not intend to cast the smallest shadow of a doubt upon his fitness for his new functions if we remark that, hitherto, he has had no adequate opportunities of demonstrating it...and the precedent of Sir William Harcourt may be cited to show hat an able barrister is presumably fitted for the discharge of the duties of a department which calls mainly for the exercise of tact, common sense, and business-like application to detail."

POSSESSING OF A NECESSARY QUALIFICATION

The Morning Post, whilst acknowledging that his appointment would probably come as a surprise to everybody, observed that Matthews might well possess certain abilities that would stand him in good stead for the post:-

...The appointment of Mr. Henry Matthews to the Home Office will probably come as a surprise to every one. The precise wisdom of it will become more clearly manifest with the lapse of time.

With the spirit, however, by which it was prompted we are as far as possible from quarrelling, seeing that it is precisely one of those concessions to the necessity for "fresh blood" which we have all along pointed out.

Mr. Matthews has distinct, if not, compared with the high dignity of his new office, distinguished credentials. As an eminent lawyer he possesses one qualification highly needed at the Home Office. As a powerful debater his presence on the front bench will lend strength to its composition.

Further than this, he has been too long absent from Parliament to provoke criticism as a public man..."

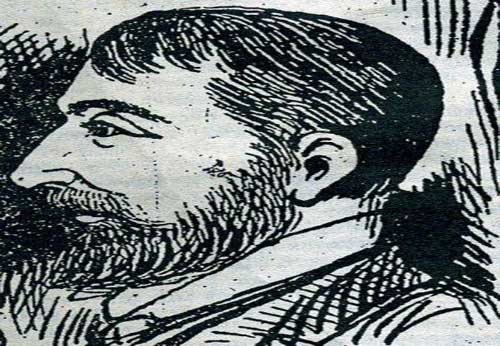

A Photograph of Sir Henry Matthews In 1890

WHAT HE WAS LIKE AS A PERSON

In February, 1887, after Matthews had completed seven months in office, The South Wales Weekly News provided the following assessment of him as a person, in its edition of Saturday, February,5th, 1887:-

...Of commanding physique, and endowed with the mental caliber necessary to withstand a strong and persistent attack from Opposition speakers, he soon made his presence felt.

As a really eminent lawyer, with a thorough knowledge of the world outside political circles too, he possessed important qualifications for a seat on the Treasury Bench.

...The vigour and depth of Mr Matthews eloquence are such as to give the impression that he is a much younger man than he is, and any stranger hearing his elaborate pleading...or witnessing his incessant activity on the front benches in Parliament, would imagine him to be a man far from the shady side of sixty.

He has quite an air of juvenility, which does not desert him when engaged in the less serious doings of life, for, off duty, his well defined features are most always suffused with a smile.

He is quite a character in the social world, and a man of many friends, for his own sake as well as because of his position.

Mr. Matthews is as wealthy as he is capable, having inherited, as well as earned, large sums of money.

Amiable and hospitable, though he has not burst the bonds of bachelorhood, he has a large and elegant London house in Carlton Gardens, which he bought in order, as he himself says, that he might "have a place to die in."

At Carlton Gardens, Mr Matthews often has his home brightened by the presence of two charming nieces, whose mother married a French gentleman, and who are great favourites with their brilliant uncle and all his visitors.

Mr Matthews is, personally, a many-sided man, very popular with the ladies, gifted with a rare imagination, a ready wit and quickness of apprehension. he is a keen character-reader, rich in resources, and, as a conversationalist, is as good a listener as he is a capital talker.

A man of multifarious pursuits, he is as pleasant a companion in the club smoking room as he is on the hunting field...He has all the accomplishments of a cultured mover in the best London circles..."

A GREAT DEAL OF PROMISE

Unfortunately, for someone whose appointment seemed to herald so much promise, Sir Henry Matthews' tenure as Home Secretary was to prove an unmitigated disaster, marred as it was by several PR disasters, frequent clashes with the three Chief Commissioners of the Metropolitan Police - Sir Charles Warren, James Monro and Sir Edward Bradford - who served under him, and bouts of political unrest in both London and Ireland.

The Penny Illustrated paper, on August 17th, 1889 had this to say of him:-

...He is clever enough - no one has ever doubted that. A more eloquent pleader, a smarter lawyer, a better after-dinner speaker never lived.

Until Mr. Matthews became a minister, everybody united in praise of him.

He was popular at his circuit Mess; the judges thought highly of him; no career seemed to lofty for him.

As Home Secretary, he was tried in the critical place - and found wanting. In a word, he is an able man, but weak. He has heaps of talent, but he wants judgment..."

A STRONG MAN WAS NEEDED

Unfortunately, the post of Home Secretary required a much stronger and decisive individual at the time of his appointment and over the four years that followed his appointment, and it could be argued that Sir Henry Matthews was the right man, in the right job at the wrong time.

Even Queen Victoria felt compelled to express her disappointment with him during the Jack the Ripper murders, by writing to the Prime Minister, Lord Salisbury, to tell him that, as far as she could see, Sir Henry Matthews's, "general want of sympathy with the feelings of the people are doing the Government harm."

Tellingly, Salisbury replied that there was, "..an innocence of the ways of the world which no one could have expected to find in a criminal lawyer of sixty."

A GOOD START

And yet, it all started reasonably well.

Matthews arrived in Office to find a war going on between James Monro, the Assistant Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police and head of the Criminal Investigation Department, and Sir Edward George Jenkinson, a shadowy spymaster, who was waging a covert battle against the threat of Fenian terrorism, and whose official designation, "Assistant Under-Secretary for Crime and Police in Ireland", belied an impressive, though extremely secretive, network of spies in London, Ireland, Mexico and America.

Monro had taken up his post in 1884, and for the next two years had become vexed by the fact that Jenkinson was running several secret operations, using a network of agents and informants in London and Europe, without bothering to consult with Monro in his capacity as Assistant Police Commissioner and head of the Metropolitan Police's detective department.

By the time Sir Henry Matthews became Home Secretary, in the summer of 1886, Jenkinson and Monro loathed one another, and were engaged in a bitter power struggle.

JAMES MONRO WINS THE BATTLE

In December, 1886, Monro emerged the victor from the struggle, and Henry Matthews wrote to Jenkinson to inform him that, "after much anxious consideration, I have determined to relieve you from your present duties as speedily as possible and I fix the 10th January as a convenient day..."

In early 1887, Jenkinson's department was closed down, and the work he had been doing to thwart Fenian terrorist attacks in London was handed over to James Monro, to be run from his office at 21, Whitehall Place.

A new secret national security service was set up under Monro, which was variously known as "Section D", "the Secret Department", or "the Home Office Crime Department."

TWO ROLES AND TWO SUPERIORS

Monro now had two roles, and two separate bosses.

In his role as Assistant Metropolitan Police Commissioner, his immediate superior would the Chief Commissioner, Sir Charles Warren.

However, in his capacity as head of the new Secret Department, he would report directly to Warren's superior, Sir Henry Matthews.

In other words, Warren, as Metropolitan Police Commissioner, found himself in the awkward - and, as he saw it, untenable - position of having a subordinate over much of whose work he had neither say nor control.

For a military man, used to being in control, this was, to say the least, an extremely un-military arrangement.

Matthews appears to have forged ahead with the arrangements without any consideration for the feelings, or pride, of his Chief Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, and Warren was left to bristle with indignation.

However, for the time being Warren, reluctantly, accepted the situation.

THE MISS CASS CASE

At around 10pm on the night of 28th June, 1887, 24-year Elizabeth Cass went out to purchase a pair of gloves from Jay's, millinery shop at 243 to 253 Regent Street in the West End of London, and was arrested by Police Constable Bowden Endacott, on suspicion of soliciting for purposes of prostitution.

The next morning, she appeared before Stipendiary Magistrate Robert Milnes Newton at Great Marlborough Street Police Court, where she proclaimed her innocence, and was discharged with a caution.

As she left the dock, Mr Newton warned her that, if she was as respectable as she claimed to be, she should refrain from walking along Regent Street at 10 o'clock at night.

On 30th June, 1887, Miss Cass's employer, Mrs Bowman, wrote to Scotland Yard to complain at how her employee had been treated by the police.

HENRY MATTHEWS QUESTIONED IN PARLIAMENT

On Friday, 1st July, 1887, Llewellyn Atherley-Jones, the Member of Parliament for North West Durham, raised the issue of Miss Cass's arrest, and the fact that the magistrate had, effectively, branded any woman who went out on her own on Regent Street at night a prostitute, raised the matter with Henry Matthews in Parliament.

Matthews admitted that there was no independent corroboration of PC Endacott's assertion that Miss Cass had been soliciting on Regent Street, but added that the magistrate saw no reason to disbelieve the constable.

Mr Joseph Chamberlain, M.P. for Birmingham West, then asked:-

...whether, considering the very serious injury which could have been done to an innocent person if any mistake had been made, and the fact the magistrate was in some doubt on the subject, the Right Honourable Gentleman could not, consistently with his duty, make some further inquiry as to the character of the employer and the girl herself."

Matthews stated that he had questioned the magistrate, Mr Newton:-

The magistrate said that, knowing the officer to be trustworthy, his evidence left no doubt whatever in his mind.

Of course, however, there would be no objection to make any inquiry such as that which the Right Honourable gentleman suggested."

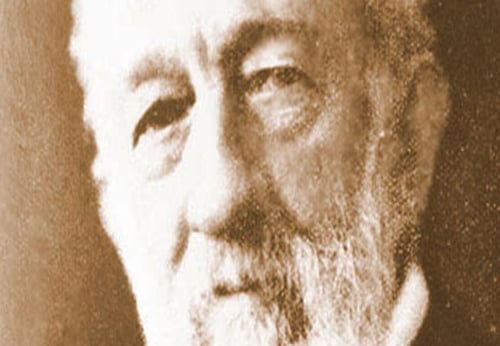

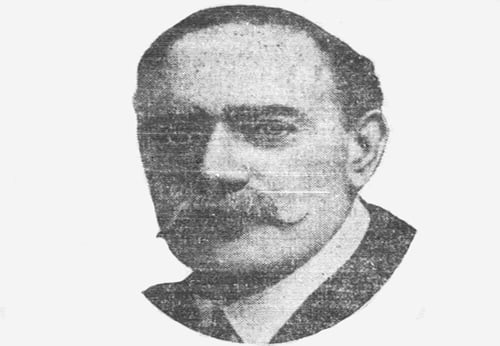

Llewellyn Atherley-Jones

1851 - 1929

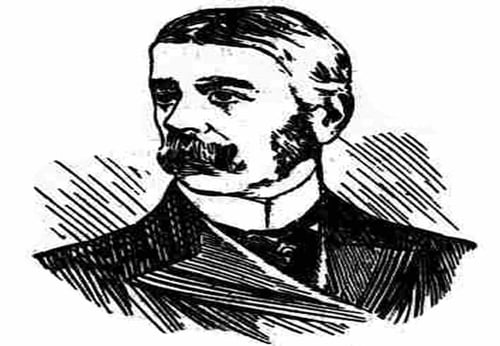

Joseph Chamberlain

1836 - 1914

MATTHEWS FORCED TO BACK DOWN

On the 5th July, 1887, Atherley-Jones again quizzed the Home Secretary in the House of Commons, and asked Matthews if he had, as he had promised to Mr. Chamberlain, made further inquiry into the case of Miss Cass and, if so,what was the result of the inquiry.

The replies that Henry Matthews gave were considered to be somewhat flippant, and, as a consequence, he was forced into a humiliating climb down and had no choice but to launch an official enquiry into Police Constable Endacott's treatment of Miss Cass.

Although the enquiry, which was chaired by the Metropolitan Police Commissioner, Sir Charles Warren (no conflict of interest there then!), supported Endacott, Miss Cass's Supporters brought an action against Endacott on charges of perjury, albeit he was acquitted at his subsequent trial later that year.

The newspapers had a field day with a case that became a cause célèbre throughout the summer of 1887, and, from that point on, Matthews found his competency as Home Secretrary consistently questioned by the media.

BLOODY SUNDAY, NOVEMBER, 1887

The next event in the litany of PR disasters presided over by Sir Henry Matthews was the "Bloody Sunday" debacle

During the summer of 1887, large numbers of the capital's unemployed had been camping out and meeting in Trafalgar Square.

Sir Charles Warren, the Metropolitan Police Commissioner, became worried by the unrest and agitation that was taking place, unchecked, in the square, and, feeling that it might well place London at the mercy of an unruly mob, he requested Henry Matthews, as Home Secretary, to ban all protests and meetings from being held in Trafalgar Square.

The Home Secretary, however, prevaricated on responding to the request of the Commissioner, and Warren had not choice but to allocate 2,000 policemen each weekend to be kept on hand to ensure that order was maintained in the Square.

Matthews finally made the decision to grant Warren's request in early November 1887; and Warren set about enforcing it without delay.

The Metropolitan Radical Federation, however, decided to challenge the ban, and they duly called a public meeting in Trafalgar Square, ostensibly to demand the release of several Irish politicians, which was to take place at 2.30pm on Sunday 13th of November 1887.

The stage was set for confrontation and, according to newspaper reports, 20,000 protestors (the police estimated twice that number, the organisers half) converged on the Square, where Warren had stationed 2,000 constables, two deep in a ring around its interior.

The resultant clash was described by many witnesses as "open warfare" between the police and the protestors, and it was soon dubbed "Bloody Sunday" by the Victorian radicals and media.

You can read a full account of "Bloody Sunday" here.

The majority of press hostility that resulted from the "Bloody Sunday" clash was aimed at Sir Charles Warren.

However, it didn't go unobserved that Matthews, as Warren's superior, had played his part in the events of the day; and, as a consequence, he too was facing increased hostility from many sections of the media, as 1888 dawned, and the Jack the Ripper murders gave the radical politicians and the media the looked for opportunity to exact their revenge on both Sir Henry Matthews and Sir Charles Warren.

Article Sources

The Times, Friday, 30th July, 1886

The Evening Standard, Friday, 30th July, 1886

The Globe, Friday, 30th July, 1886

The Morning Post, Friday, 30th July, 1886

South Wales Weekly News, Saturday, 5th February, 1887