- Major Henry Smith became the Chief Superintendent of the City of London Police in 1885.

- At the time of the murder of Catherine Eddowes, on 30th September, 1888, he was the Acting Police Commissioner.

- His willingness to share information made him one of the most popular police officers in the eyes of the press.

- Unlike his Metropolitan Police counterparts, he actually believed that the Lusk Kidney was genuine.

- Site Author and Publisher Richard Jones

- Richard Jones

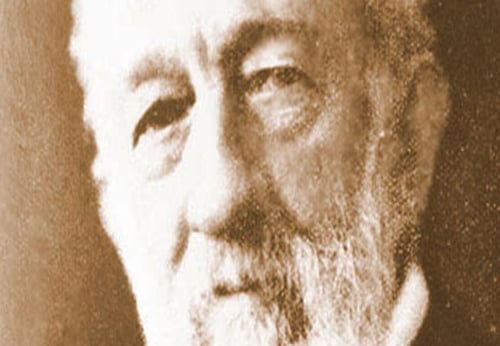

SIR HENRY SMITH

ACTING CITY OF LONDON POLICE COMMISSIONER

Major Henry Smith (1835 - 1921), was the Acting City of London Police Commissioner at the time of the murder of Catherine Eddowes, which took place in Mitre Square, in the City of London, on 30th September, 1888.

Unlike his Metropolitan Police counterpart, Sir Charles Warren, he proved himself to be very adept at handling the "gentlemen of the press", and, as a result of his willingness to share information, the City Police got a better press than the Metropolitan Police during the Jack the Ripper scare.

RELATED TO ROBERT LOUIS STEVENSON

Born in Penpont, Dumfriesshire, his father, grandfather, great grandfather, and great-great grandfather had all been ministers with the Church of Scotland.

Smith could boast literary connection in that he was the cousin once removed of Scottish novelist Robert Louis Stevenson (1850 - 1894), and paid many a visit to the novelist's childhood home at 17, Heriot Row, in Edinburgh.

Evidently, he absorbed some of his cousin's talent for storytelling, as he later became renowned for his skills as a raconteur, albeit he was never one to let the facts get in the way of a good yarn!

Having completed his education in Edinburgh, he was articled as a Chartered Accountant, a training that was to stand him in good stead during his later career in the City of London Police.

JOINS THE CITY OF LONDON POLICE

Arriving in London in the 1879 Major Henry Smith sought employment in the senior ranks of the police and, in 1885, achieved his quest when he was appointed the Chief Superintendent of the City of London Police.

POLICE COMMISSIONER FOR 11 YEARS

Following the retirement of Sir James Fraser, in 1890, Major henry Smith succeeded him as City of London Police Commissioner, and remained in the post for the next 11 years.

However, in 1901, he became considered that his force didn't have a sufficient number of men to cope with special occasions, and so he wrote to the Lord Mayor requesting an increase in numbers.

The Police Committee of the Corporation of the City of London, however, rejected his request and, instead, suggested that the force did not require augmentation on normal days, and so they ruled that it would be sufficient to draft in men from outside to cope on special occasions.

The Committee, therefore, proposed a scheme whereby a permanent reserve of superannuated constables would be raised.

Smith didn't think that this would prove adequate, and so he resigned.

Looking back on his tenure in the Commissionership, in its edition of Saturday 28th December, 1901, Freeman's Exmouth Journal commented how, "under his directorship, the force has sustained its reputation, the highest in the world, for good character and efficiency."

THE JACK THE RIPPER MURDERS

When the Jack the Ripper murders occurred, in the autumn of 1888, the City Police Commissioner Sir James Fraser was away on leave, and Smith was standing in as Acting Commissioner in his absence.

Since the murder of Catherine Eddowes, on the 30th September, 1888, took place in Mitre Square, just inside the City's eastern boundary, the investigation of it fell to the City of London Police, which meant that Smith, as the acting chief, was in charge.

THE WHITECHAPEL MURDERS

Recalling the Whitechapel murders in his memoirs From Constable to Commissioner: The Story of Sixty Years Most of Them Misspent, published in 1910, Smith had this to say:-

In August, 1888, when I was desperately keen to lay my hands on the murderer, I made such arrangements as I thought would insure success.

I put nearly a third of the force into plain clothes, with instructions to do everything which, under ordinary circumstances, a constable should not do. It was subversive of discipline; but I had them well supervised by senior officers.

The weather was lovely, and I have little doubt they thoroughly enjoyed themselves, sitting on door-steps, smoking their pipes, hanging about public-houses, and gossiping with all and sundry.

In addition to this, I visited every butcher's shop in the city, and every nook and corner which might, by any possibility, be the murderer's place of concealment.

Did he live close to the scene of action? or did he, after committing a murder, make his way with lightning speed to some retreat in the suburbs? Did he carry something with him to wipe the blood from his hands, or did he find means of washing them? were questions I asked myself nearly every hour of the day.

It seemed impossible he could be living in the very midst of us; and, seeing the Metropolitan Police had orders to stop every man walking or driving late at night or in the early morning, till he gave a satisfactory account of himself, more impossible still that he could gain Leytonstone, Highgate, Finchley, Fulham, or any suburban district without being arrested.

The murderer very soon showed his contempt for my elaborate arrangements.

The excitement had toned down a little, and I was beginning to think he had either gone abroad or retired from business, when "Two more women murdered in the East!" raised the excitement again to concert pitch."

NEWS OF THE MURDER

On the night of Saturday the 29th September, 1888, he was spending a restless night at Cloak Lane Police Station, alongside Southward Bridge, when the bells above his head suddenly began to ring:-

..."What is it?" I asked, putting my ear to the tube.

"Another murder, sir, this time in the City."

Jumping up, I was dressed and in the street in a couple of minutes. A hansom-to me a detestable vehicle-was at the door, and into it I jumped, as time was of the utmost consequence. This invention of the devil claims to be safe. It is neither safe nor pleasant. In winter you are frozen; in summer you are broiled. When the glass is let down your hat is generally smashed, your fingers caught between the doors, or half your front teeth loosened. Licensed to carry two, it did not take me long to discover that a 15-stone Superintendent inside with me, and three detectives hanging on behind, added neither to its comfort nor to its safety.

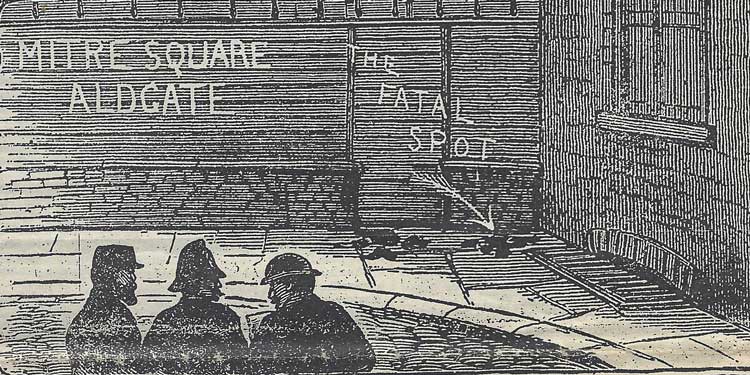

Although we rolled like a "seventy-four" in a gale, we got to our destination - Mitre Square - without an upset, where I found a small group of my men standing round the mutilated remains of a woman..."

The Murder Spot In Mitre Square.

From The Illustrated Police News, Saturday, October 6th, 1888

THE KIDNEY WAS GENUINE

Interestingly, Major Henry Smith was almost a lone voice amongst police officers in that he believed that the portion of kidney, which was sent to Mr George Lusk with the "From Hell" letter, was, in fact, genuine.

As he put it in his memoirs:-

When the body was examined by the police surgeon, Mr. Gordon Brown, one kidney was found to be missing, and some days after the murder what purported to be that kidney was posted to the office of the Central News, together with a short note of rather a jocular character unfit for publication.

Both kidney and note the manager at once forwarded to me. Unfortunately, as always happens, some clerk or assistant in the office was got at, and the whole affair was public property next morning.

Right royally did the Solons of the metropolis enjoy themselves at the expense of my humble self and the City Police Force.

"The kidney was the kidney of a dog, anyone could see that," wrote one. "Evidently from the dissecting-room," wrote another. "Taken out of a corpse after a post-mortem," wrote a third. "A transparent hoax," wrote a fourth.

My readers shall judge between myself and the Solons in question.

I made over the kidney to the police surgeon, instructing him to consult with the most eminent men in the profession, and send me a report without delay.

I give the substance of it. The renal artery is about three inches long. Two inches remained in the corpse, one inch was attached to the kidney. The kidney left in the corpse was in an advanced stage of Bright's Disease; the kidney sent me was in an exactly similar state.

But what was of far more importance, Mr. Sutton [this is a reference to Henry Gawen Sutton], one of the senior surgeons of the London Hospital, whom Gordon Brown asked to meet him and another practitioner in consultation, and who was one of the greatest authorities living on the kidney and its diseases, said he would pledge his reputation that the kidney submitted to them had been put in spirits within a few hours of its removal from the body -thus effectually disposing of all hoaxes in connection with it.

The body of anyone done to death by violence is not taken direct to the dissecting-room, but must await an inquest, never held before the following day at the soonest..."

HE WAS WRONG ABOUT THE KIDNEY

It should be noted that Sutton was a respected and distinguished physician, so if Smith did, as he claims, seeks his opinion then he cannot be easily dismissed.

However, it should also be noted that Smith was wrong when he stated that the kidney had been posted to the office of the central News, as it was, in fact, sent to Mr. George Lusk. It was actually the Dear Boss letter that was sent to the Central News.

SIR ROBERT ANDERSON

In the same year that, by then, Sir Henry Smith wrote his memoirs, Sir Robert Anderson, the Assistant Metropolitan Police Commissioner in 1888, also wrote his memoirs, entitled The Lighter Side of My Official Life.

In those memoirs Sir Robert claimed that Jack the Ripper had, in fact, been a low class Polish Jew living in the locality whose people knew of his guilt but refused to give him up to Gentile justice.

Smith was highly critical of Anderson's accusation ad observed that:-

..Sir Robert discourses on the Whitechapel, or Jack the Ripper, murders, and states emphatically that he, the criminal, was living in the immediate vicinity of the scenes of the murders, and that, if he was not living absolutely alone, his people knew of his guilt and refused to give him up to justice.

"The conclusion," Sir Robert adds, "we came to was that he and his people were low-class Jews, for it is a remarkable fact that people of that class in the East End will not give up one of their number to Gentile justice, and the result proved that our diagnosis was right on every point."

Sir Robert does not tell us how many of "his people" sheltered the murderer, but whether they were two dozen in number, or two hundred, or two thousand, he accuses them of being accessories to these crimes before and after their committal.

Surely Sir Robert cannot believe that while the Jews, as he asserts, were entering into this conspiracy to defeat the ends of justice, there was no one among them with sufficient knowledge of the criminal law to warn them of the risks they were running?

Sir Robert talks of the "Lighter Side" of his Official Life. There is nothing "light" here; a heavier indictment could not be framed against a class whose conduct contrasts most favourably with that of the Gentile population of the Metropolis..."

THE RIPPER BEAT HIM

No doubt if Smith and Anderson met each other, in the wake of the publication of their respective memoirs, the atmosphere was, to say the least, somewhat frosty.

But, you have to give Major henry Smith credit for one thing.

Whereas Anderson was happy to boast that jack the Ripper had not evaded him and the case had been solved; Smith was willing to concede that the murderer had, indeed, evaded capture.

As he put it in his memoirs:-

There is no man living who knows as much of those murders as I do; and ... I must admit that, though within five minutes of the perpetrator one night, and with a very fair description of him besides, he completely beat me and every police officer in London; and I have no more idea now where he lived than I had twenty years ago..."

Article Sources

Freeman's Exmouth Journal Saturday, December 28, 1901.

The Dundee Evening Telegraph Thursday, March 3, 1921.

From Constable to Commissioner: The Story of Sixty Years Most of Them Misspent

Chatto and Windus, 1910.