- The majority of the Whitechapel murders were investigated by officers from the Metropolitan Police.

- Due to a huge increase in London's buildings and population, by 1888 the force was suffering from a severe understaffing problem.

- The problem was particularly noticeable in the Detective Department of the Metropolitan Police.

- Site Author and Publisher Richard Jones

- Richard Jones

THE CRIMINAL INVESTIGATION DEPARTMENT 1878 - 1888

THE DETECTIVE FORCE OF SCOTLAND YARD

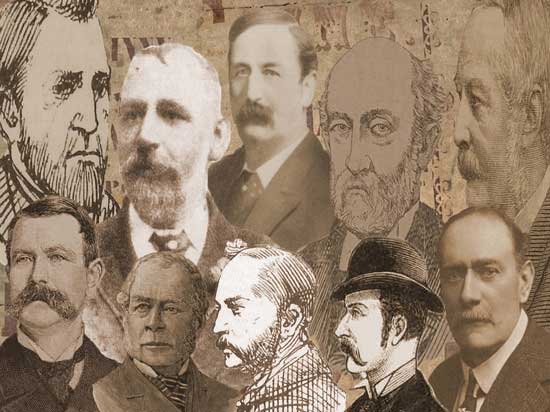

During the autumn of 1888 - and throughout the years that followed - the Victorian detectives of the Metropolitan Police pitted their wits against an unknown killer who confronted them with a type of crime that they had little or no experience of dealing with.

As they threshed around, looking for an elusive break that might help them crack the case and bring the perpetrator to justice, they began to refine their investigative techniques and, in so doing, began to gain an understanding of the basic principles of a crime scene investigation.

THE FOUNDING OF THE CRIMINAL INVESTIGATION DEPARTMENT

Although the Metropolitan Police had been enforcing law and order on the streets of the Metropolis since 1829, the Criminal Investigation Department, or CID, had been in existence for just ten years when the Whitechapel Murders began.

The CID itself had been founded in April 1878 following a re-organisation of the original Scotland Yard Detective Branch after several of its detectives had been jailed having being exposed as being in the pay of a gang of swindlers.

This new department was put under the command of a vigorous, and ambitious barrister by the name of Howard Vincent who, although given the official title of "Director of Criminal Investigations", was, in all but name, the Assistant Police Commissioner.

Howard Vincent.

PRESS CRITICISM

However, the first ten years of this fledgling Criminal Investigation Department, were anything but a smooth ride for the detectives who worked there.

The detectives had been subjected to an awful lot of press criticism from the likes of Punch Magazine, which quickly dubbed them the "defective department."

Furthermore, those first ten years were marred by constant in-fighting and power struggles between senior officers, Home Office officials and various political mandarins - so much so that, by 1888, the ordinary everyday detectives who worked there were, to say the least, somewhat demoralised.

HOWARD VINCENT RESIGNS AND JAMES MONRO ARRIVES

By May 1884, Howard Vincent had decided that his position at the helm of a bickering detective department held out little promise of advancement and he had been trying to resign for over a year.

When on 30th May 1884, Fenian terrorists succeeded in detonating a bomb directly under the office of Scotland Yard's Special (Irish) Branch, Vincent decided enough was enough and he resigned to pursue a career as a Tory Member of Parliament.

REPLACED BY JAMES MONRO

His replacement was a dour Scot by the name of James Monro, who quickly found himself at odds with Edward Jenkinson, a shadowy figure who was running a secret, and secretive, Home Office Department tasked with infiltrating the Irish Fenian Terrorists who, at the time, were conducting a bombing campaign on the British mainland.

Monro was highly suspicious of Jenkinson's secretive and decidedly dubious methods and it is safe to say that the two of them enjoyed a working relationship of mutual loathing and extreme mistrust.

James Monro.

ROBERT ANDERSON AND THE WRATH OF JENKINSON

One person for whom Jenkinson held as much animosity as he did for Monro was Robert Anderson, a Dublin born lawyer, who had been brought to London in 1867 as a member of the specially formed Counter Revolutionary Secret Service Department, part of the fight against the threat of Fenian terrorism.

When that Department was disbanded, in 1868, the Home Secretary had invited Anderson to stay on in London as Home Office Adviser On Irish Affairs and Political Crime.

As the Fenian campaign in London increased throughout the early 1880s, Anderson became more and more involved in the fight against terrorism.

In March 1884, Edward Jenkinson was allowed to form his own Secret Department, working under the auspices of the Home Office, and this department was meant to liaise with Anderson who would collate the intelligence that the new branch was collecting.

It wasn't long, however, before Anderson found himself at loggerheads with Jenkinson, who had little respect for Anderson, trusted him even less, and, in consequence, did all in his power to sideline Anderson.

The contempt that Jenkinson held for Anderson is amply demonstrated in the following letter, which he wrote to Earl Spencer, following Anderson's appointment as head of the Criminal Investigation Department in August, 1888:-

It is quite true that R. Anderson has been appointed to succeed Monro as Head of the Criminal Inv Dept at Scotland Yard. What an infamously bad appointment it is!

Anderson is not the 19th part of a man, and if it were known what kind of man he is, there would be a howl all over London..."

However, Anderson's promotion to head of the CID was two years in the future when, on 9th May, 1886, Jenkinson succeeded in having him formally "relieved of all duties relative to Fenianism in London."

Removed from his position, Anderson was compensated with the role of secretary to the prison commissioners, and, for the time being, Jenkinson had the upper hand against Monro.

Robert Anderson.

SIR CHARLES WARREN BECOMES COMMISSIONER

As Monro and Jenkinson bickered between themselves; in January, 1886 a new Metropolitan Police Commissioner was appointed.

His name was Sir Charles Warren, and, two years later, he would find his competency questioned in the press on an almost daily basis as the police poured their resources into trying to catch Jack the Ripper.

HIS FORCE WAS UNDERMANNED

Questions of his competency aside, Warren inherited a Police force that was severely undermanned and, the fact that many of his available officers were being allocated to the protection of Public officials and buildings from the ever present threat of terrorism, exacerbated the problem even further.

In his annual report on the Policing of the Metropolis for 1887 Warren pointed out that:-

London of today, with its 5,476,447 inhabitants and 8773 police to protect them, is in far worse case than the London in 1848, when 2,473,758 persons had an available strength 0f 5288 police to look after their safety..."

JENKINSON FORCED FROM OFFICE

Meanwhile, the in fighting between Monro and Jenkinson had come to a head and, in January 1887, Jenkinson was forced from office, and his secret Home Office Department was promptly closed down to be replaced by a new department, known as Section D, of which James Monro was given command alongside his duties as head of the Criminal Investigation Department.

ROBERT ANDERSON BROUGHT BACK

Needing an intelligence expert, Monro brought back Jenkinson's old foe Robert Anderson, and appointed him his "Assistant in Secret Work."

The two men soon became close friends as well as colleagues.

A PROFESSIONAL CONFLICT

Unfortunately, Monro's two jobs caused something of a professional conflict for him.

As head of the CID, he was accountable to the Metropolitan Police Commissioner, Sir Charles Warren. But as head of Section D he reported directly to the Home Office.

This placed Warren in the untenable position of having a subordinate officer over some of whose duties he had neither authority or influence, and this, in turn, sowed the seeds for discord between the two most senior Metropolitan Police officers.

POLICE NUMBERS

One bone of contention between the two men was that Monro considered the number of detectives under his command to be woefully inadequate.

There were, so the Pall Mall Gazette reported, "...not quite 300 men, all told, 80 of whom are inspectors and 120 sergeants, with less than a hundred other distributed about the twenty-two metropolitan divisions..."

Monro had recognised the need for more detectives if the Metropolis was to be effectively policed and he duly applied to Warren for an increase in man power.

Warren was adamant that no such increase was necessary, and he argued that constables in plain clothes were just as effective as detectives.

MONRO RESIGNS

In late 1887, Monro complained to Warren that he was overworked, and he suggested that a friend of his, Melville Macnaghten, be appointed Assistant Chief Constable.

However, Warren vetoed Macnaghten's appointment and, as a result, Monro resigned as head of the CID.

His resignation became effective on August 31st 1888, the day, as it happened, of what is generally accepted as the first Jack the Ripper Murder, that of Mary Nichols.

ANDERSON TAKES OVER

His replacement was Robert Anderson.

Anderson's Secret work had, however, left him suffering with exhaustion and, as result, his doctor advised an immediate recuperative break.

So, within a week of taking up his post as head of the CID, Anderson left London for Switzerland, and the hapless detectives serving under him, who had watched the animosity between Warren and Monro escalate, now found themselves leaderless as the Jack the Ripper crimes escalated and stretched their resources to the limits.