- The Jack the Ripper murders were the subject of a huge police operation.

- As the killings increased in their ferocity, the police found themselves subjected to growing press and public criticism.

- One of the biggest criticisms was that no reward was being offered that might lead to the perpetrator being identified..

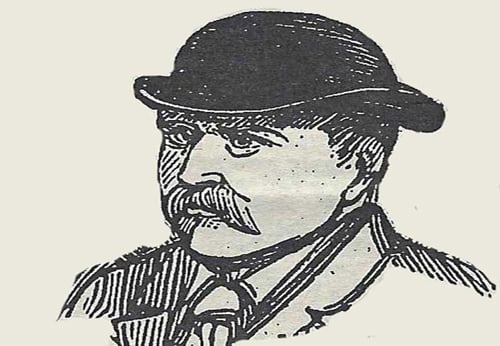

- Site Author and Publisher Richard Jones

- Richard Jones

HOW THE POLICE INVESTIGATED THE JACK THE RIPPER CRIMES

THE JACK THE RIPPER CSI

In the early days of the Jack the Ripper Police investigation the general consensus amongst the police and the public alike was that the crimes were gang related.

WERE THE CRIMES GANG-RELATED?

On 7th September 1888 The Weekly Herald, commenting on the police investigation into the Jack the Ripper murders (which at that point were known as the "Whitechapel Murders") reported on the murder of Mary Nichols, – which had taken place on 31st August 1888 – that:-

The officers engaged in the case are pushing their inquiries in the neighbourhood as to the doings of certain gangs known to frequent the locality, and an opinion is gaining ground amongst them that the murderers are the same who committed the two previous murders near the same spot. It is believed that these gangs, who make their appearance during the early hours of the morning, are in the habit of blackmailing these unfortunate women, and when their demands are refused violence follows, and in order to avoid their deeds being brought to light they put away their victims. They have been under the observation of the police for some time past, and it is believed that, with the prospect of a reward and a free pardon, some of them might be persuaded to turn Queen's evidence, when some startling revelations might be expected."

LOCAL KNOWLEDGE

In early September 1888 the powers that were at Scotland Yard (the headquarters of the Metropolitan Police) decided that local knowledge was what was needed if the perpetrator of the Whitechapel Murders was to be apprehended.

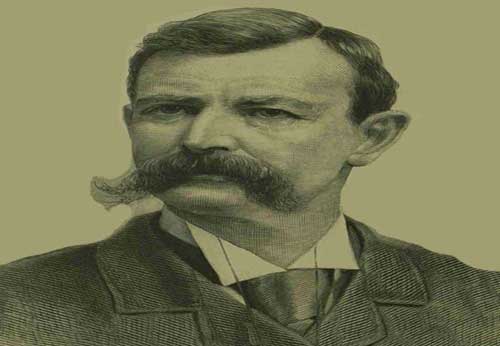

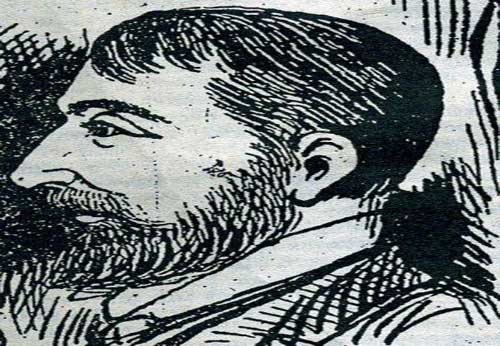

INSPECTOR ABBERLINE BROUGHT IN

To this end, Inspector Frederick George Abberline – an officer who had been promoted out of the area the previous December after fourteen years spent patrolling and getting to know the neighbourhood and its criminal elements – was drafted back into the district to take overall charge of the on the ground Jack the Ripper police investigation.

It was evidently believed that Abberline’s local knowledge would prove invaluable in hunting down the killer and bringing him to justice.

DID THE RIPPER KNOW HIS VICTIMS?

An important aspect of a murder investigation is looking at the victim’s immediate circle and ascertaining who amongst them had a motive and the opportunity to commit the crime. However, since Jack the Ripper was an opportunist killer, who most certainly did not know his victims, this would have been of little use to Abberline and his fellow detectives.

So, since the victims didn’t know their killer and it was, therefore, impossible to identify their murderer amongst their associates, the Victorian detectives had to fall back upon other methods of trying to trace him.

High on their list of police investigative methods would have been a thorough knowledge of the local criminals. This is where, it was believed, Abberline’s knowledge of the locality would come in useful. It was hoped that a little, well applied, police persuasion might cause one of the local villains to turn informer and hand the murderer to the police. But since Jack the Ripper probably worked alone and, in all likelihood, was not a member of the local criminal fraternity, this line of enquiry was ultimately doomed to failure.

MISTRUST OF THE PRESS

One aspect of the police investigation into the Jack the Ripper killings that was radically different to how a murder enquiry might be handled today was that the police didn’t make a great deal of use of the press. Indeed, there had long been a certain amount of distrust towards the press in police circles.

In the early days of the CID Howard Vincent had adopted a policy that the police were, under no circumstances, to talk to journalists about their cases. He stated that:-

Police must not on any account give any information whatever to gentlemen connected with the press, relative to matters within police knowledge, or relative to duties to be performed or orders received, or communicate in any manner, either directly or indirectly, with editors, or reporters of newspapers, on any matter connected with the public service, without express and special authority...The slightest deviation from this rule may completely frustrate the ends of justice, and defeat the endeavour of superior officers to advance the welfare of the public service. Individual merit will be invariably recognized in due course, but officers, who without authority give publicity to discoveries, tending to produce sensation and alarm, show themselves wholly unworthy of their posts."

A major fear - and possibly a very reasonable one - was that if the police were to tell journalists about the lines of enquiry they were following, then the subsequent press reportage might well tip off possible suspects that the police were on to them. Early in the investigation the police had seen the danger posed by sensationalist press reportage when the Leather Apron scare almost set off an anti-Jewish pogrom in the East End of London. Thus the police chose to try and keep journalists at arm’s length in order to keep their lines of enquiry from becoming public knowledge.

PRESS COVERAGE OF THE CRIMES

However - and unfortunately for the police - the ripper crimes generated a huge amount of press coverage and the general public were desperate to pore over every salacious detail of the case.

Starved of news by the police, journalists adopted several means of obtaining information. They would shadow individual constables or detectives in the hope they would lead them to a suspect or a witness. They would track down and interview witnesses to see if they could glean a hint as to what stage, if any, the police investigation had reached. They would try to bribe officers or attempt to loosen their tongues with drink. Some journalists even dressed up as women and set off into the streets of Whitechapel in the hope that they might be accosted by Jack the Ripper and, in so doing, gain a sensational scoop for their newspaper. And, when all else failed, they could always make up stories.

FALSE LEADS AND ANTI-SEMITISM

Ultimately the antics of the popular press proved counterproductive to the police investigation into the Jack the Ripper murders, since the reporting threw up so many false leads and red herrings that the, already overstretched, detectives were stretched almost to breaking point.

Also, the anti- Semitism that stories such as the Leather Apron scare provoked diverted valuable police resources, such as on the ground constables, away from trying to prevent another ripper outrage to simply maintaining public order in the area.

WHY WAS NO REWARD OFFERED?

Another subject of intense debate throughout the Jack the Ripper scare was whether or not a reward should be offered by the authorities in order to induce someone to come forward with information that might lead to the killer’s apprehension.

At the inquest into the death of Mary Nichols the foreman of the jury had stated that had a reward been offered by the Government after the murder of Martha Tabram then "very probably the two later murders (Mary Nichols and Annie Chapman) would not have been perpetrated."

Although the police attracted a huge amount of criticism over "their" refusal to offer a reward, it was in fact a Home Office policy rather than a police policy not to offer on.

In November 1888, Henry Matthews, the Home Secretary, addressed the House of Commons and defended his decision not to offer a reward:-

Before 1884 it was the common practice for the Home Office to offer rewards, and sometimes large amounts, in the case of serious crimes.

In 1883 in particular several rewards, ranging from £200. to £2,000, were offered in such cases as the murder of Police-constable Boans, and the dynamite explosions in Charles-street.

These rewards, like the £10,000 reward for the Phoenix Park murders, were ineffectual, and produced no evidence of any value.

In 1884 there was a change in policy. A remarkable case occurred. A conspiracy was formed to effect an explosion at the German Embassy, to plant papers upon an innocent person, and to accuse him of the crime, in order to obtain the reward which was expected.

The revelation of this conspiracy led the then Secretary of State (Sir W. Harcourt) to consider the whole question.

He consulted the police authorities both in England and in Ireland, and the conclusions he arrived at were "that the practices of offering large sensational rewards in cases of serious crime is not only ineffectual, but mischievous; that the rewards produce, generally speaking, no practical result beyond satisfying a public demand for conspicuous action; that they operate prejudicially, by relaxing the exertions of the police, and that they have tended to produce false rather than reliable testimony."

He decided, therefore, in all cases to abandon the practice of offering rewards, as they had been found by experience to be a hindrance rather than an aid in the detection of crime.

These conclusions were publicly announced and acted upon in two important cases in 1884.

One was a shocking murder and violation of a little girl at Middlesborough, and the other the dynamite outrage at London-bridge, in which case the City offered £5,000 reward.

The whole subject was reconsidered in 1885 by Sir R. Cross in a remarkable case of infanticide at Plymouth, and again in 1886 by the right hon. gentleman the member for Edinburgh (Mr. Childers) in the notorious case of Louisa Hart. In both cases, with the concurrence of the best authorities, the principle was maintained, and a reward refused.

Since I have been at the Home Office I have followed the rule thus laid down and steadily adhered to by my predecessors. I do not mean that the rule may not be subject to exceptions, as for instance where it is known who the criminal is, and information is wanted only as to his hiding-place, or on account of other circumstances of the crime itself.

In the Whitechapel murders not only are these conditions wanting at present, but the danger of a false charge is intensified by the excited state of public feeling.

I know how desirable it is to allay that public feeling, and I should have been glad if the circumstances had justified me in giving visible proof that the authorities are not heedless or indifferent.

I beg to assure...the House that neither the Home Office nor Scotland-yard will leave a stone unturned in order to bring to justice the perpetrators of these abominable crimes which have outraged the feelings of the entire community.

It should be noted that, despite the Home Offices refusal to offer a reward, several private individuals, as well as the Lord Mayor of the City of London, did offer rewards, none of which resulted in the killer's apprehension.

PROBLEMS FOR POLICE INVESTIGATION

The 1888 police, therefore, could only pursue their enquiries in the hope that a lucky break might lead them

Indeed, just how unhelpful the prospect of a reward could prove is amply demonstrated by a report that appeared in the Daily News on 13th October 1888:-

The lapse of time diminishes the prospect of the discovery of the Whitechapel murderer. No attempt is made by the police themselves to disguise the fact that arrest upon arrest, each equally fruitless, has produced in the official minds a feeling almost of despair.

A corps of detectives left Leman street yesterday morning, and the officer, under whose direction they are pursuing their investigations, had in their possession quite a bulky packet of papers all relating to information supplied to the police, and all, as the detective remarked, "amounting to nothing."

"The difficulty of our work," he said, "is much greater than the general public are aware of."

In the first place there are hundreds of men about the streets answering the vague description of the man who is "wanted" and we cannot arrest everybody.

The reward for the apprehension of the murderer has had one effect - it has inundated us with descriptions of persons into whose movements we are expected to inquire for the sole reason that they have of late been noticed to keep rather irregular hours and to take their meals alone.

Some of these cases we have sent men to investigate, and the persons who it has proved have been unjustly suspected have been very indignant, and naturally so. The public would be exceedingly surprised if they were made aware of some of the extraordinary suggestions received by the police from outsiders.

Why, in one case, the officer laughingly remarked, it was seriously put to us that we should carefully watch the policeman who happened to be on the particular beat within the radius of which either of the bodies was found.

The amount of work done by the detectives through this series of crime has been, he added, enormous.

We do not expect that the batch of inquiries to be undertaken today will lead to any more satisfactory result than those of previous days..."

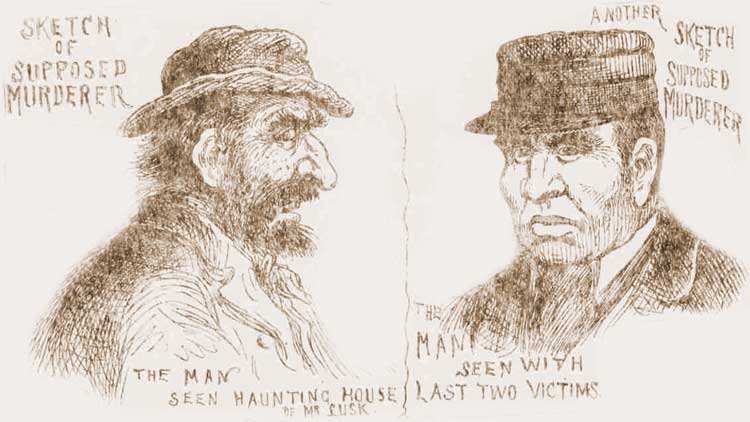

ARTIST IMPRESSIONS OF THE KILLER

The mention of “vague descriptions” in the article is quite interesting because, fabricators aside, there were some important witnesses who may have seen the face of Jack the Ripper. However, another valuable tool that the police would utilise today that wasn’t used a great deal in the Jack the Ripper investigation was an artist’s impression of what the killer might have looked like based on witnesses who may have seen him with his victims. There were several people who may have seen the face of the ripper and an artist’s composite published in every London newspaper may well have brought an identification of a suspect from a neighbour or even a family member.

On 20th October 1888, the Illustrated Police News did publish two suspect sketches. However, these were little more than an artist’s impression of what an evil and villainous murderer such as Jack the Ripper should have looked like, as opposed to an accurate depiction of suspects based on witness descriptions.

THEY DIDN'T HELP

As such they did little to help with the hunt for Jack the Ripper and may well have hindered it since the police were inundated with tip-offs about anyone who bore even the slightest resemblance to these crude suspect sketches.