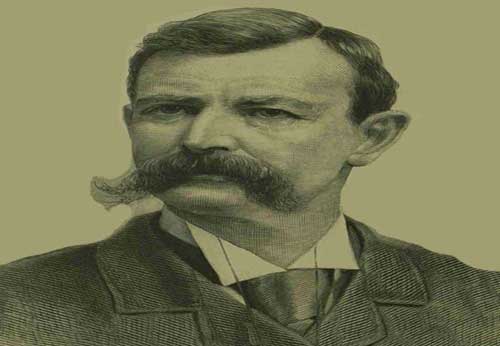

- Inspector Frederick George Abberline was the detective who led the on the ground investigation into the Jack the Ripper murders.

- He had previously spent fourteen years as head of the Criminal Investigation Department of H Division.

- The previous year (1887) he had been promoted and transferred to the Detective Department at Scotland Yard.

- In early September, 1888, he was sent back to H Division to take charge of the hunt for the Whitechapel murderer.

- Site Author and Publisher Richard Jones

- Richard Jones

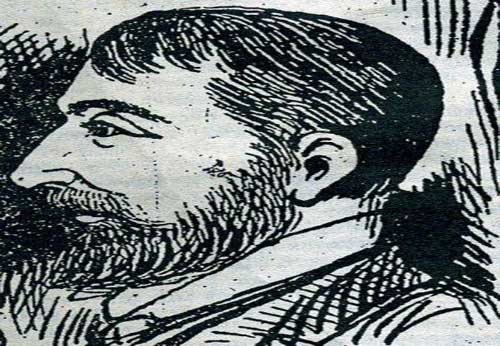

INSPECTOR FREDERICK GEORGE ABBERLINE

THE LEAD INVESTIGATOR 1888 - 1889

Frederick George Abberline (1843 - 1929) was the detective who led the on the ground investigation into the Jack the Ripper throughout the autumn and winter months of 1888.

He had joined the Metropolitan Police on 5th January 1863 (warrant number 43519) and had spent a great deal of his career policing the streets of Whitechapel and Spitalfields.

Walter Dew, who was a young detective officer with H division at the time of the Whitechapel murders - and who in time would rise through the ranks and achieve fame as the man who arrested wife murderer Dr. Hawley, Harvey Crippen - was based throughout the murders at Commercial Street Police Station.

In his memoirs, I Caught Crippen, Dew had this to say about his old boss:-

Inspector Abberline was portly and gentle speaking.

The type of police officer - and there have been many - who might easily have been mistaken for the manager of a bank or a solicitor.

He also was a man who had proved himself in many previous big cases.

His strong suit was his knowledge of crime and criminals in the East End, for he had been for many years the detective-inspector of the Whitechapel Division, or as it was called then the "Local Inspector."

Inspector Abberline was my chief when I first went to Whitechapel.

He left only on promotion to the Yard, to the great regret of myself and others who had served under him. No question at all of Inspector Abberline's abilities as a criminal hunter.”

Walter Dew

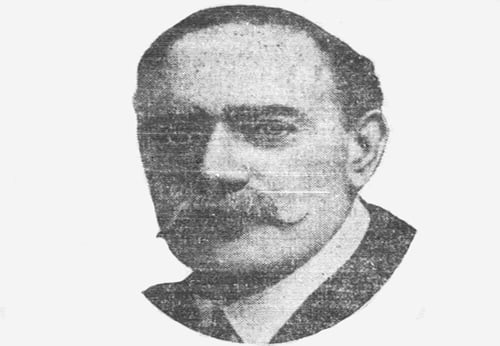

Frederick Abberline

THE SENIOR OFFICER ON THE CASE

Inspector Frederick George Abberline was 45 years old in 1888. He was a portly and balding officer who wore a thick moustache and bushy side whiskers.

He had already spent fourteen years as a detective with H division and had gained an unrivalled knowledge of the area’s streets and criminals.

Toby praised him as:-

A well known East Ender…[to whom] scores of persons are indebted…He has a decent amount of curiosity, and has been known to stop gentlemen at the most unholy times and places and enquire about their health and work – questions which are often settled by a magistrate, generally in Mr. Abberline’s favour."

PROMOTED TO SCOTLAND YARD

The previous year Abberline’s dedication and service were recognised with a promotion to Central Office at Scotland Yard, and a farewell dinner was held for him in December 1887 at the Unicorn Tavern, on Shoreditch High Street.

However, it was decided early on in the Jack the Ripper case that the local detective force would benefit from the involvement of experienced officers from Scotland Yard.

In his memoirs, Dew mentioned how Chief Inspector Moore [in fact, Moore was still an Inspector in 1888], Inspector Abberline and Inspector Andrews were sent from Scotland Yard to head the on the ground investigation, “assisted, of course, by a large number of officers of subordinate rank.”

THE MURDER OF MARY NICHOLS

Abberline was first called in to give an opinion on the crimes in the immediate aftermath of the murder of Mary Nichols, which took place on 31st August, 1888.

The St James's Gazette mentioned his involvement in the case in its edition of Saturday. September 1st, 1888:-

So far the police have satisfied themselves, but as to getting a clue to her murderer they express little hope. The matter is being investigated by Detective. Inspector Abberline, of Scotland-yard, and Inspector Helson, J division..."

HE LOCATED MARY NICHOLS'S HUSBAND

Abberline was evidently much involved with the investigation into Mary Nichols's murder at this point, and was, according to the following article, which appeared in The East London Observer, on Saturday, 8th September, 1888, and which concerned his appearance, on Saturday, September 1st, 188, at the first day of the inquest into the death of Mary Nichols, busily following up leads and tracing witnesses in the days immediately proceeding the murder:-

Detective-inspector Abberline asked for an adjournment of some length, as certain things were coming to the knowledge of the police, and they wished for time to make inquiries.

The coroner required that on Monday he should like to hear on Monday the two butchers who had been referred to...

Inspector Abberline having stated that the butchers had been summoned, a juryman asked if the husband could be produced?

"Yes," said Inspector Abberline, and, immediately after the inquiry had been adjourned till Monday he proceeded to find the husband and brought him to the mortuary.

So soon as the lid of the shell had been removed, he looked at the contents, and then, with a shudder, turned to Inspector Abberline and said it was his wife..."

ANNIE CHAPMAN'S MURDER

By the time of the murder of Annie Chapman, on the 8th September, 1888, he was seen very much as the lead officer on the case, as is attested to by the following snippet, which appeared in The Cambridge Chronicle and Journal, on Friday, 14th September, 1888:-

...Detective Sergeant Thicke, Sergeant Leach, and other detective officers were soon on the spot [the backyard of 29 Hanbury Street where Annie Chapman's murder had occurred], while a telegram was sent to Inspector Abberline at Scotland-yard apprising him of what had happened.

It will be recollected that this officer assisted in the inquiry concerning the murder in Buck's Row..."

THE WORK OF THE SAME HAND?

Of course, one of the first things that the police had to consider, in the wake of this latest atrocity, was whether or not it was the work of the same person who had carried out the murder of Mary Nichols a week earlier.

There was, in fact, little doubt that the same perpetrator had carried out all three murders, as was reported by The Herts and Cambs Reporter on Friday, 14th September, 1888:-

Detective-inspector Abberline of Scotland-yard, who had been detailed to make special inquiries as to the murder of Mary Ann Nichols, at once took up the inquiries with regard the new crime, the two being obviously the work of the same hands.

He held a consultation with Detective-inspector Helson, J Division, in whose district the murder in Buck's-row was committed, and with Acting-Superintendent West, in charge of H Division.

The result of that consultation was an agreement in the belief that the crimes were the work of one individual only, that the murders were committed where the bodies had been found, and that they were not the work of any gang..."

THE ARREST OF WILIAM HENRY PIGOTT

On Monday, 10th September, 1888. Abberline was the officer who headed to Gravesend to escort William Henry Pigott(1835 - 1901) back to London.

Pigott had been arrested the previous evening in the Pope's Head Tavern, in West Street, Gravesend.

The Central News Agency reported that his, "...hand is badly bitten, and there are blood marks on his clothes. He answers somewhat to the description published on the man wanted. He admits to having been in Whitechapel on the Saturday morning, about the place where the woman's body was found..."

Evidently, it was believed that Pigott was a promising potential suspect, and, no doubt, Abberline was looking forward to an elusive breakthrough in the case as he headed to Gravesend.

The Morning Star took up the story in its edition of Tuesday, September, 11th, 1888:-

In response to a telegram apprising him of the arrest Inspector Abberline proceeded to Gravesend yesterday morning, and decided to bring the prisoner at once to Whitechapel, so that he could be confronted with the women who had furnished the description of "Leather Apron."

A considerable crowd had gathered at Gravesend railway station to witness the departure of the detective and the prisoner, but his arrival at London-bridge was almost unnoticed, the only persons apprised of the journey beforehand being the police, a small party of whom were in attendance in plain clothes.

Inspector Abberline and the prisoner went off at once in a four-wheel cab to Commercial-street Police Station, where from early morning groups of idlers had hung about in anticipation of an arrest.

The news of Pigott's arrival at once spread, and in a few seconds the police-station was surrounded by an excited crowd anxious to get a glimpse of the supposed murderer.

Finding that no opportunity of seeing the prisoner was likely to occur, the mob, after a time, dispersed, but the police had trouble for some hours in keeping the thoroughfare free for traffic.

Pigott arrived in Commercial-street in much the same condition as when taken into custody. He wore no vest, had on a battered felt hat, and he appeared to be in a state of great nervous excitement.

Mrs. Fiddymont, who is responsible for the statement respecting a man resembling "Leather Apron" being at the "Prince Albert" on Saturday, was sent for, as were also other persons likely to be able to identify the prisoner, but after a very brief scrutiny it was the unanimous opinion that Pigott was not "Leather Apron."

Nevertheless it was decided to detain him until he could give a somewhat more satisfactory explanation of himself and his movements.

After an interval of a couple of hours the man’s manner became more strange, and his speech more incoherent, the divisional surgeon was called in, and gave it as his opinion that the prisoner's mind was unhinged.

A medical certificate to this effect was made out, and Pigott will for the present remain in custody."

ELIZABETH STRIDE'S MURDER

In the wake of the murder of Elizabeth Stride, Abberline was being recognised as the lead detective on the case, albeit, he was now sharing the burden of the murders investigation with Chief Inspector Donald Swanson.

Reporting on the police activity in the immediate aftermath of the Stride murder, The Scotsman, on Monday, 1st October, 1888, informed its readers that, "After the police authorities had been notified of the murder, the case was given into the hands of Chief Inspector Swanson and Inspector Abberline of Scotland Yard..."

THE MURDER OF MARY KELLY

In the aftermath of the murder of Mary Kelly, Abberline, was soon on the scene, and one of his first actions was, according to The Dundee Courier, on Saturday, 10th November, 1888, was to give "... orders that no-one should be allowed to enter or leave the court." He then, according to the article, "waited a little and then sent a telegram to Sir Charles Warren to bring the bloodhounds so as to trace the murderer if possible..."

Abberline also had the Unenviable task of sifting through the ashes of the grate in Mary Kelly's room to see if they could yield up any clues.

According to his inquest testimony, as reported in The Manchester Times on Saturday, 17th November, 1888:-

...I went to Miller's Court at 11.30am on Friday. When there I received information that the bloodhounds were on their way. I waited till 1.30pm, when Superintendent Arnold arrived and said that the order for the bloodhounds had been countermanded.

The door was then forced.

In the grate were traces of women's clothing having been burnt.

My opinion is they were burnt to give sufficient light for the murderer to do his work."

INTERVIEWED GEORGE HUTCHINSON

Abberline also interviewed George Hutchinson, the witness who claimed to have seen Mary Kelly in the company of a man on Commercial Street in the early hours of the morning on which she had been murdered. Hutchinson said that he actually followed the couple, and had watched them go into Miller's Court.

Abberline seems to have taken Hutchinson's account of what he had seen very seriously, and he even assigned two detectives to escort him around the district, in the hope that he might see the man and identify him.

However, as with so many previous leads, this came to nothing; and today people even question whether Abberline might not have been a little too trusting of Hutchinson's claims.

LEAVES THE INVESTIGATION

By 1889, Abberline had been removed from the Whitechapel murders investigation - we don't actually know why - and, by July 1889, he had been replaced by Inspector Henry Moore as the officer in charge of the on the ground investigation.

He would go on to investigate the Cleveland Street scandal, and several other cases that were reported in the national press between 1889 and 1892.

1892 RETIRES FROM THE METROPOLITAN POLICE

Inspector Frederick George Abberline retired from the Metropolitan Police on the 8th of February, 1892.

The Pall Mall Gazette carried the announcement of his "pending" retirement - which had been tendered a month earlier, but which would take effect once his investigation into the case he was working on at the time had been concluded - in its edition of Friday, 4th March, 1892:-

It is reported that Mr. F. Abberline, Chief Inspector of the Criminal Investigation Department, is about to retire after thirty years' service.

Mr Abberline's retirement (says the Exchange Telegraph Company) will be felt as a great loss to Scotland-yard, where he has always been regarded as one of the most efficient officers of the Department, and was constantly entrusted with cases requiring courage, skill and discretion.

He has consequently had opportunities of distinction in connection with some of the most important investigations with which Scotland-yard has had to deal.

His retirement takes effect when his duties in connection with what is known as "the great bond robbery" have been completed."

LOST IN THEORIES

A few months later, free of the restrictions that had been placed on him whilst a serving officer, he gave an interview to a reporter from Cassell's Saturday Journal, in which he held forth on the problems that he had faced during the Jack the Ripper investigation.

Interestingly, he also gave it as his opinion that the murder of Mary Kelly had, in fact, been the last actual murder committed by Jack the Ripper.

The journal published the interview in it edition of Saturday, 22nd May, 1892:-

[Mr Abberline's] knowledge of crime and the people who commit it is extensive and peculiar.

There is no exaggeration in the statement that, whenever a robbery or offence against the law had been committed in the district, the detective knew where to find his man and the property too.

His friendly relations with the shady folk who crowd into the common lodging houses enabled him to pursue his investigations connected with the murders with the greatest certainty, and the facilities afforded him made it clear to his mind that the miscreant was not to be found lurking in a "dossers" kitchen.

In fact, the desire of the East Enders to assist the police was so keen that the number of statements made - all of them requiring to be recorded and searched into - was so great that the officer almost broke down under the pressure.

His anxiety to bring the murderer to justice led him, after occupying the whole day in directing his staff, to pass his time in the streets until early morning, driving home fagged and weary at 5am. And it happened frequently, too, that just as he was going to bed, he would be summoned back to the East End by a telegraph, there to interrogate some lunatic or suspected person whom the inspector in charge would not take the responsibility of questioning

"Theories!"exclaims the inspector, when conversing about the murders – we were lost almost in theories; there were so many of them.

...Nevertheless, he has one which is new. He believes from the evidence of his own eyesight that the Miller's Court atrocity was the last of the real series, the others having been imitations, and that in Miller's Court the murderer reached the culminating point of gratification of his morbid ideas..."

A few months later, on Wednesday 8th June, 1892, the people of the East End, in conjunction with Abberline's former colleagues from H Division, held a farewell dinner for him.

The guest list is interesting in that present at the dinner was John McCarthy, the landlord of 13 Miller's Court, the room in which Mary Kelly had been murdered 4 years before.

The East London Observer published a full account of the dinner and the speeches given in its edition on Saturday, 11th June 1892:-

On Wednesday evening, on the occasion of his retirement from the service, Chief Inspector Frederick G. Abberline, of the Criminal Investigation Department, was entertained at dinner at the "Three Nuns Hotel" by a number of his friends, and was made the recipient of a handsome presentation.

Although, as a matter of fact, Mr. Abberline has retired from the force now for some little time, and was made, on the occasion of his retirement from Scotland Yard, the recipient of a presentation by his brother officers, it was thought by the tradesmen of East London and others who knew Mr. Abberline there, to be only appropriate to mark, by another presentation, their appreciation of the services of Mr. Abberline while stationed - as he was for a considerable number of years - with the H Division, and discharging his duties in the interests of the district.

The result was the dinner on Wednesday evening, over which Mr. Isaac Davis presided, supported by, in addition to the guest of the evening, Messrs. F. Louisson, H. Gluckstein, J. C. McDonald, C. A. McDonald, D. Older, H. Brooks, M. Joseph, J. W. Galton, F. W. Ayres, R. A. Kearsey, H. Gibbs, E. J. Anning, Anning, jun., H. Allan Thorpe, J. Hawkins, J. Levy, I. Abrahams, J. McCarthy and McCarthy, jun., Superintendents Shore, Butcher, Arnold, and Jones, Chief Inspector Peel, Inspectors Jarvis, Moore, Conquest, Hare, Richards, Turrell, Willson, Kitchner, Melville, Regan, and Froest, and Messrs. Hodson, Thornton, and others.

At the conclusion of the proposition of the usual loyal toasts, Mr. E. J. Anning, rising amid cheers, said he had had the distinguished honour conferred upon him in the name of those who were present, and of the still larger public outside, of offering for Mr. Abberline's acceptance, the very handsome silver tea and coffee service which lay before him, and which was the outcome of the high estimation in which he was held by all in East London. (Hear, hear.)

The inscription on the silver salver, which accompanied the service, recorded the fact that for thirty years Mr. Abberline had been engaged in the honorable service of that department of our system which had for its object the detection of crime.

He thought that if he were to attempt to tell them of all the exploits in which Mr. Abberline had been engaged during that time, he should have to ask them to stay for another thirty years while he recounted them.

The profession in which their distinguished guest of that evening had been engaged was one of a very honorable character, and he who carried out the duties connected with it in the honorable way which had been done by Mr. Abberline, was a man of whom not only they, but society at large, might be proud. (Applause.)

The British individual, as a rule, was a great grumbler. He knew that ever since he had seen the light - and it was, he presumed, very much the same before he did - his experience had been that John Bull was a great grumbler, not only against his country in general, but also against all the institutions of his country.

In his grumbling he had not failed to grumble also at the department of the police service relating to the detection of crime.

John Bull had either heard, or read, or been told, that they managed this business very much better in other countries, and compared our system - very much to its disadvantage - with what he chose to call the admirable systems of France, Russia, Germany, and America.

But, for all that, he knew perfectly well that what they did in those countries under the authority of the police would not for a single hour be tolerated in free England. (Cheers.)

The detection of crime in some of the countries to which he had alluded was easy, and when one heard of some very great feat performed by the detective departments in those parts, they knew as a matter of fact that there had been very little trouble at all about the detection and arrest of the criminal.

Not so in this country.

The ramifications of crime here were very minute, and very difficult to detect and the service often got very little credit for the most difficult and daring undertakings. (Hear, hear.)

He would say nothing - because it would take up too much of their time - about what Mr. Abberline had done in the course of his honoured career.

He need only mention Cunningham and Burton, and barely allude to what occurred on board a certain Channel boat, and a bare allusion to those matters was quite sufficient to remind them of some of the matters in which Mr. Abberline had been engaged.

They were all, he was sure, glad and proud to be there that evening to ask his acceptance of that testimonial. It would enable him in future to look back upon what he was sure would be one of the most pleasant evenings in his life.

The termination of his official career, which had been one of the most adventurous character, must be gratifying, not only to himself, but to all who where gathered there that evening, because they had now Mr. Abberline entirely amongst them - he would not say full of years, for he was comparatively young as yet, but certainly full of honour. (Cheers.)

When, in after years, Mr. Abberline looked upon that presentation, he would, he was persuaded, remember that it was a proof of the high regard in which he was held by all with whom he came in contact, and, on their part, those who came after him would also remember, when they looked at it, that it was given in recognition of the services of a man of whom the country had every reason to be proud. (Applause.)

The speaker concluded by asking Mr. Abberline’s acceptance of the silver tea and coffee service, which was magnificently chased, and contained the following inscription:- "This testimonial is presented to Mr. F. G. Abberline, late Chief Inspector of the Criminal Investigation Department, Scotland Yard, on his retirement from the police force after a service of nearly thirty years, by a few friends, as a mark of their esteem and regard, and in appreciation of his services as a police officer, and the rectitude of character and gentlemanly bearing exhibited by him on all occasions. Signed on behalf of the Committee J. C. McDonald, Hon. Secretary, June 8th, 1892."

The presentation was accomplished amid the greatest enthusiasm, and the toast of Mr. Abberline's health was cordially honoured.

Replying, Mr. Abberline, who was again received with enthusiasm, expressed his high appreciation of the great kindness which had been shown him that evening, and, indeed, in so many quarters, since he had retired from the police force.

He was deeply sensible of the great compliment which had been paid him by the presentation of that testimonial, and he took that opportunity to express to all who had been engaged in its promotion, his heartiest thanks.

He was especially glad to see so many of his old colleagues rally round him that evening to bid him an official good-bye. He could only hope that he would merit their esteem and retain their friendship. (Cheers.)

He would retain very pleasant recollections of his services in East London. He was fully convinced that any man who did his duty in the East End honourably, honestly, and fearlessly, would find no more ardent supporters and no truer friends than were to be found there.

Nor was there in all London any quarter that interested itself more largely in the cause of charity than did the East End.

As a proof of that, he need only refer to the large number of charitable societies with which his friend Mr. McDonald was associated, and he could only trust that in due time his services in that direction would be rewarded as they so richly deserved to be. (Hear, hear.)

He thanked them again sincerely, and assured them that he would always remember the many happy evenings he had spent in East London, and the very great kindness he had met from everybody there. (Loud cheers.)

The Chairman, in proposing the toast of "The Metropolitan Police," mentioned the fact that they now numbered over fifteen thousand men, and spoke of their services in the direction of protecting life and limb and property in terms of the warmest praise.

Superintendent Arnold, of the H Division, in replying, took the gathering of that night to prove how greatly the services of the police were appreciated in East London.

For several years Mr. Abberline had served under him in the H Division, and he assured them that he had found no better officer in the service. (Hear, hear.)

In losing him he felt that he was losing his right hand, and that he would have the utmost difficulty in replacing him.

He felt bound to tell them, however, that when he was in trouble - as he was during the continuance of the Whitechapel crimes - Mr. Abberline came down to the East End and gave the whole of his time with the object of bringing these crimes to light.

Unfortunately, however, the circumstances were such that success was impossible, but he could assure them that it was through no fault of Mr. Abberline's that they did not succeed.

With regard to himself, he could only say that for 37 years he had served in the police force, both in the East and West End of London, and that he had never received heartier or better support than he had found among the people of East London. (Cheers.)

Superintendents Shore and Butcher also responded, both of them taking the opportunity to speak in warm terms of the services of Mr. Abberline.

Mr. Kearsey proposed "The Health of the Committee" in a characteristically genial and appropriate speech, adding that if longer time had been given, and the appeal had been more extended, not one, but several testimonials could have been obtained for Mr. Abberline, so generally and even universally respected was he. (Hear, hear.)

Mr. J. C. McDonald, as one who had for 19 years been a comrade of Mr. Abberline's, expressed, in replying, his pleasure at the successful issue of that presentation..."

ABBERLINE TO THE RESCUE

Following his retirement, Abberline went to work as a private investigator, albeit, as the following story illustrates, he could always be relied on to come to the assistance of any police officers who found themselves in jeopardy.

In March, 1897, the Sunderland branch of the North-Eastern Bank was robbed of upwards of £7,000 in gold and notes.

On Saturday, June 5th, 1897, Chief Inspector Jarvis, of Scotland Yard, assisted by Inspector Turrell and Sergeant Williamson, believed they had traced several members of the gang responsible to a public house, in Bateman-street, Soho, London, and they duly moved in to apprehend the suspects.

The Pall Mall Gazette, on Monday, 7th June, 1897 recounted what happened next:-

..Chief Inspector Jarvis and his colleagues at once rushed into the tavern, seized their men, and hurried them out of the place and into a four-wheeled cab before they had recovered from their surprise.

Before, however, the cab could drive off cries of "Chivey them" were raised, and in a moment a mob of men began to attack the cab.

So numerous were the assailants that, by force of weight, they nearly overturned the cab, smashing the doors and windows, and forcing the detectives and their prisoners out on the pavement.

At this moment, the struggle attracted the attention of Mr. Abberline, a Scotland Yard inspector, recently retired on a pension, and he promptly went to the assistance of the detectives, and rendered effective help, though he was badly knocked about in doing it.

By this time, the detectives were struggling with upwards of a hundred men. The fight was an unequal one, as the detectives were not armed, and ultimately one of the prisoners was rescued. The second man was finally got out of the crowd and taken to the police-station.

A telegram to Sunderland brought Inspector Burdy from that town to London, and last evening he started north with the prisoner.

The man who escaped is an ex-convict of powerful physique, and the police hope to recapture him before long.

Chief Inspector Jarvis and the other detectives engaged in the capture were all badly bruised and strained in the struggle.

Inspector Turrell also injured his shoulder, Sergeant Williamson was kicked in the body, and Mr. Abberline, who arrived so opportunely on the scene, was severely mauled."

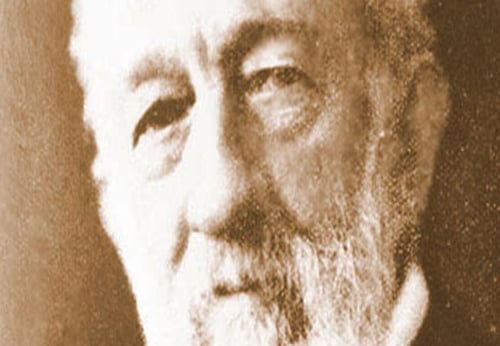

Frederick Abberline

Inspector Jarvis

HIS THEORY ON JACK THE RIPPER

Abberline, on the whole, remained tight-lipped about any theories he may have had concerning the identity of Jack the Ripper.

However, following the conviction of George Chapman, for wife-poisoning, in 1903, there were suggestions in the newspapers that Chapman may have been responsible for the Whitechapel murders, and a reporter from Pall Mall Gazette, approached Abberline at his residence in Clapham Road, London, to seek his opinion on the claims.

His views on the possibility were published by the Gazette on 24th March 1903:-

...the retired detective said:- "What an extra- ordinary thing it is that you should just have called upon me now. I had just commenced, not knowing anything about the report in the newspaper, to write to the Assistant Commissioner of Police, Mr. Macnaghten, to say how strongly I was impressed with the opinion that 'Chapman' was also the author of the Whitechapel murders. Your appearance saves me the trouble.

I intended to write on Friday, but a fall in the garden, injuring my hand and shoulder, prevented my doing so until today."

Mr. Abberline had already covered a page and a half of foolscap, and was surrounded with a sheaf of documents and newspaper cuttings dealing with the ghastly outrages of 1888.

"I have been so struck with the remarkable coincidences in the two series of murders," he continued, "that I have not been able to think of anything else for several days past - not, in fact, since the Attorney-General made his opening statement at the recent trial, and traced the antecedents of Chapman before he came to this country in 1888. Since then the idea has taken full possession of me, and everything fits in and dovetails so well that I cannot help feeling that this is the man we struggled so hard to capture fifteen years ago.

My interest in the Ripper cases was especially deep.

I had for fourteen years previously been an inspector of police in Whitechapel, but when the murders began I was at the Central Office at Scotland Yard.

On the application of Superintendent Arnold I went back to the East End, just before Annie Chapman was found mutilated, and as chief of the detective corps I gave myself up to the study of the cases.

Many a time, even after we had carried our inquiries as far as we could - and we made out no fewer than 1,600 sets of papers respecting our investigations - instead of going home when I was off duty, I used to patrol the district until four or five o'clock in the morning, and, while keeping my eyes wide open for clues of any kind, have many and many a time given those wretched, homeless women, who were Jack the Ripper's special prey, fourpence or sixpence for a shelter to get them away from the streets and out of harm's way."

"As I say," went on the criminal expert, "there are a score of things which make one believe that Chapman is the man; and you must understand that we have never believed all those stories about Jack the Ripper being dead, or that he was a lunatic, or anything of that kind.

For instance, the date of the arrival in England coincides with the beginning of the series of murders in Whitechapel; there is a coincidence also in the fact that the murders ceased in London when 'Chapman' went to America, while similar murders began to be perpetrated in America after he landed there.

The fact that he studied medicine and surgery in Russia before he came here is well established, and it is curious to note that the first series of murders was the work of an expert surgeon, while the recent poisoning cases were proved to be done by a man with more than an elementary knowledge of medicine.

The story told by 'Chapman's' wife of the attempt to murder her with a long knife while in America is not to be ignored, but something else with regard to America is still more remarkable.

While the coroner was investigating one of the Whitechapel murders he told the jury a very queer story.

You will remember that Dr. Phillips, the divisional surgeon, who made the post-mortem examination, not only spoke of the skillfulness with which the knife had been used, but stated that there was overwhelming evidence to show that the criminal had so mutilated the body that he could possess himself of one of the organs.

The coroner, in commenting on this, said that he had been told by the sub-curator of the pathological museum connected with one of the great medical schools that some few months before an American had called upon him and asked him to procure a number of specimens. He stated his willingness to give £20 for each.

Although the strange visitor was told that his wish was impossible of fulfillment, he still urged his request. It was known that the request was repeated at another institution of a similar character in London.

The coroner at the time said:- "Is it not possible that a knowledge of this demand may have inspired some abandoned wretch to possess himself of the specimens? It seems beyond belief that such inhuman wickedness could enter into the mind of any man; but, unfortunately, our criminal annals prove that every crime is possible!"

"It is a remarkable thing," Mr. Abberline pointed out, "that after the Whitechapel horrors America should have been the place where a similar kind of murder began, as though the miscreant had not fully supplied the demand of the American agent.

There are many other things extremely remarkable.

The fact that Klosowski when he came to reside in this country occupied a lodging in George Yard, Whitechapel Road, where the first murder was committed, is very curious, and the height of the man and the peaked cap he is said to have worn quite tallies with the descriptions I got of him.

All agree, too, that he was a foreign-looking man, - but that, of course, helped us little in a district so full of foreigners as Whitechapel.

One discrepancy only have I noted, and this is that the people who alleged that they saw Jack the Ripper at one time or another, state that he was a man about thirty-five or forty years of age. They, however, state that they only saw his back, and it is easy to misjudge age from a back view."

Altogether Mr. Abberline considers that the matter is quite beyond abstract speculation and coincidence, and believes the present situation affords an opportunity of unravelling a web of crime such as no man living can appreciate in its extent and hideousness."

GEORGE R. SIMS DISAGREES

On the following Sunday, George R. Sims, writing under his pseudonym of "Dagonet" in The Referee, dismissed Abberline's theory:-

..."It is perfectly well known at Scotland Yard who 'Jack' was and the reasons for the police conclusions were given in the report to the Home Office which was considered by the authorities to be final and conclusive..."

ABBERLINE RESPONDS TO SIMS

The Pall Mall Gazette, reporter paid a return visit to Abberline, who was only too willing to dismiss Sims's complaints one by one.

The next interview with him was published on Tuesday, 31st March, 1903

Since the Pall Mall Gazette a few days ago gave a series of coincidences supporting the theory that Klosowski, or Chapman, as he was for some time called, was the perpetrator of the "Jack the Ripper" murders in Whitechapel fifteen years ago, it has been interesting to note how many amateur criminologists have come forward with statements to the effect that it is useless to attempt to link Chapman with the Whitechapel atrocities.

This cannot possibly be the same man, it is said, because, first of all, Chapman is not the miscreant who could have done the previous deeds, and, secondly, it is contended that the Whitechapel murderer has long been known to be beyond the reach of earthly justice.

In order, if possible, to clear the ground with respect to the latter statement particularly, a representative of the Pall Mall Gazette again called on Mr. F. G. Abberline, formerly Chief Detective Inspector of Scotland Yard, yesterday, and elicited the following statement from him:-

"You can state most emphatically," said Mr. Abberline, "that Scotland Yard is really no wiser on the subject than it was fifteen years ago.

It is simple nonsense to talk of the police having proof that the man is dead.

I am, and always have been, in the closest touch with Scotland Yard, and it would have been next to impossible for me not to have known all about it.

Besides, the authorities would have been only too glad to make an end of such a mystery, if only for their own credit."

To convince those who have any doubts on the point, Mr. Abberline produced recent documentary evidence which put the ignorance of Scotland Yard as to the perpetrator beyond the shadow of a doubt.

"I know," continued the well-known detective, "that it has been stated in several quarters that 'Jack the Ripper' was a man who died in a lunatic asylum a few years ago, but there is nothing at all of a tangible nature to support such a theory."

Our representative called Mr. Abberline's attention to a statement made in a well-known Sunday paper, in which it was made out that the author was a young medical student who was found drowned in the Thames.

'Yes,' said Mr. Abberline, "I know all about that story. But what does it amount to? Simply this. Soon after the last murder in Whitechapel the body of a young doctor was found in the Thames, but there is absolutely nothing beyond the fact that he was found at that time to incriminate him. A report was made to the Home Office about the matter, but that it was 'considered final and conclusive' is going altogether beyond the truth.

Seeing that the same kind of murders began in America afterwards, there is much more reason to think the man emigrated.

Then again, the fact that several months after December, 1888, when the student's body was found, the detectives were told still to hold themselves in readiness for further investigations seems to point to the conclusion that Scotland Yard did not in any way consider the evidence as final."

"But what about Dr. Neill Cream? A circumstantial story is told of how he confessed on the scaffold - at least, he is said to have got as far as "I am Jack --" when the jerk of the rope cut short his remarks."

"That is also another idle story," replied Mr. Abberline. "Neill Cream was not even in this country when the Whitechapel murders took place.

No; the identity of the diabolical individual has yet to be established, notwithstanding the people who have produced these rumors and who pretend to know the state of the official mind."

"As to the question of the dissimilarity of character in the crimes which one hears so much about," continued the expert, "I cannot see why one man should not have done both, provided he had the professional knowledge, and this is admitted in Chapman's case.

A man who could watch his wives being slowly tortured to death by poison, as he did, was capable of anything; and the fact that he should have attempted, in such a cold- blooded manner to murder his first wife with a knife in New Jersey, makes one more inclined to believe in the theory that he was mixed up in the two series of crimes.

What, indeed, is more likely than that a man to some extent skilled in medicine and surgery should discontinue the use of a knife when his commission - and I still believe Chapman had a commission from America - came to an end, and then for the remainder of his ghastly deeds put into practice his knowledge of poisons?

Indeed, if the theory be accepted that a man who takes life on a wholesale scale never ceases his accursed habit until he is either arrested or dies, there is much to be said for Chapman's consistency. You see, incentive changes; but the fiendishness is not eradicated.

The victims, too, you will notice, continue to be women; but they are of different classes, and obviously call for different methods of despatch..."

Article Sources

Register of Leavers From The Metropolitan Police. MEPO 4/339/141

St James's Gazette, Saturday, 1st September, 1888.

The East London Observer, Saturday, 8th September, 1888

The Morning Star, Tuesday, 11th September, 1888

The Herts and Cambs Reporter,, Friday, 14th September, 1888

The Cambridge Chronicle and Journal, Friday, 14th September, 1888

The Scotsman,, Monday, 1st October, 1888

The Pall Mall Gazette, Friday, 4th March, 1892.

Cassell's Saturday Journal, Saturday, 22nd May, 1892.

The East London Observer, Saturday, 11th June, 1892

The Pall Mall Gazette, Tuesday, 24th March, 1903.

The Referee, Sunday, 29th March, 1903.

The Pall Mall Gazette, Tuesday, 31st March, 1903.

The Pall Mall Gazette, Monday, 7th June, 1897

Walter Dew. I Caught Crippen Blackie and Son Ltd (1938)

Paul Begg, Martin Fido and Keith Skinner. The Jack the Ripper A to Z. Headline Book Publishing Plc. (1992)

Richard Jones. Uncovering Jack The Ripper's London. New Holland Publishing (2007)