- On September 1st, 1894, Carl Feigenbaum was arrested and charged with the murder of his landlady, Mrs Juliana Hoffman, in New York.

- Although he maintained his innocence, he was found guilty of the crime and sentenced to death in November, 1894.

- After several appeals, he was executed at Sing Sing Prison on April 27th, 1896.

Shortly after his execution, his lawyer claimed that Feigenbaum had confessed to him that he had committed the Whitechapel murders.

- Site Author and Publisher Richard Jones

- Richard Jones

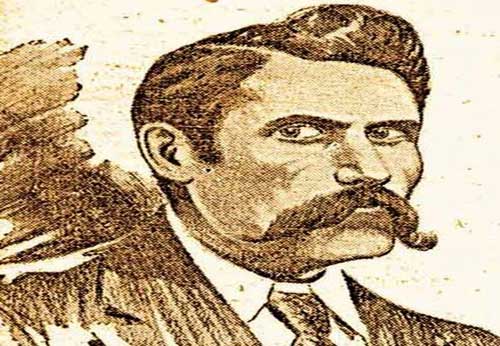

CARL FEIGENBAUM

HE CONFESSED TO THE CRIMES?

Carl Feigenbaum was most certainly a convicted murderer.

Indeed, he was convicted of and executed for the murder of Mrs Juliana Hoffman, a 56-year-old widow who lived in two rooms above a shop at 544 East Sixth Street, New York, with her 16-year-old son, Michael.

THE LODGER FEIGENBAUM

Like many poor families at the time, the Hoffmans decided to supplement the meager income that Michael brought in by renting out one of their rooms, and - as it transpired - unfortunately for them, their first lodger just happened to be Carl Feigenbaum, who moved in with them towards the end of August, 1894.

Feigenbaum told the Hoffman's that he had lost his job as a gardener, and that he, therefore, had no money. However, he assured them that he had been promised a job as a florist and that, once he was paid, on Saturday, 1st September, 1894, he would be able to pay them the rent that he owed. The Hoffmans took him at his word, a trust that would prove fatal for Mrs. Hoffman.

As a consequence of their having a lodger, who was given the rear of the two rooms, mother and son shared the front room, Juliana sleeping in the bed, and Michael occupying a couch at the foot of her bed.

THE MURDER OF MRS HOFFMAN

Shortly after midnight, in the early hours of 1st September, 1894, Michael was woken by a scream, and, looking across to his mother's bed, he saw their lodger leaning over her brandishing a knife. Michael lunged at Feigenbaum, who tuned round and came at him with the knife.

Realising he would be no match against an armed man, Michael escaped out of a window, and began screaming for help.

Looking through the window, Michael watched in horror as Feigenbaum stabbed his mother in the neck, and then cut her throat, severing the jugular. Juliana made one final attempt to defend herself, and advanced towards her attacker, but she collapsed and fell to the floor.

Feigenbaum then returned to his room, escaped out of the window, climbed down into the yard, washed his hands at the pump and then he made his way out into an alleyway that led to the street.

FEIGENBAUM ARRESTED AND CHARGED

Meanwhile, a policeman and several other locals had been alerted to the unfolding horror by Michael's cries, and, as Feigenbaum emerged from the alley, he was spotted by the assembling crowd. He attempted to make a run for it, but was quickly caught, and was then taken back to the Hoffmans rooms, where Michael identified him as the man who had attacked his mother.

Charged with murder at the police station, Feigenbaum claimed that he was innocent of the murder, and said that it had, in fact, been carried out by a man named Jacob Weibel, whom he would let sneak into his room to sleep at night.

Nobody believed a word of his unconvincing story, and he was charged with killing Juliana Hoffman and his trial for murder began on October, 26th, 1894.

It had transpired that the possible motive for the murder was that he had attempted to steal money that Mrs Hoffman kept in a cupboard in her room, and that Mrs Hoffman had awoken and caught him in the act.

In the interim, it had also transpired that the name Carl Feigenbaum was, in fact, an alias, and that his real name was probably Anton Lahn, albeit the newspapers continuously referred to him under his alias, as opposed to using his possible real name.

TRIED, FOUND GUILTY AND EXECUTED

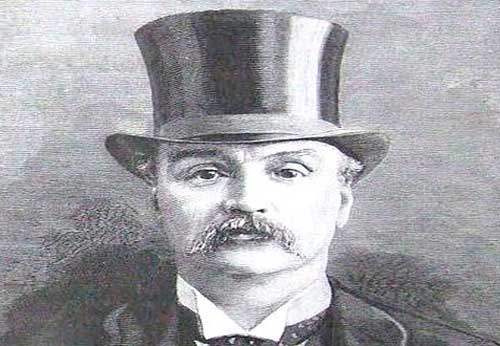

His lawyers were William Stamford Lawton and Hugh O. Pentecost.

Throughout his trial, Feigenbaum stuck to the story that he was innocent of the crime, insisting that it had been carried out by Jacob Weibel.

The jury, however, were unconvinced by his story, and they found him guilty of murder.

After several unsuccessful attempts by his lawyers to overturn his conviction, he was executed in the electric chair at Sing Sing Prison, on the 27th of April, 1896.

WHY WAS HE SUSPECTED?

You may have noticed that the above account of the crime for which Carl Feigenbaum was executed doesn't make any mention of Whitechapel, nor of his being in any way suspected of having been Jack the Ripper.

So, how did his name become linked to the Whitechapel murders of 1888?

Well, in a nutshell, he reputedly confessed to having been Jack the Ripper shortly before his execution.

It is noticeable that the British press didn't take much notice of the trial of Carl Feigenbaum - until, that is, following his execution, one of his lawyers made public an eleventh hour confession.

Suddenly, articles about his confession began appearing in British newspapers, one of which was the following report, which appeared in Reynolds's Newspaper, on Sunday, 3rd, May 1896:-

SUPPOSED EXECUTION OF JACK THE RIPPER.

An impression, based on an eleventh hour confession and other evidence, prevails that Carl Feigenbaum, who was executed at Sing Sing on Monday, the real murderer of the New York outcast, nick-named Shakespeare, is possibly Jack the Ripper, of Whitechapel notoriety.

The proofs, however, are far from positive."

HIS "CONFESSION" IN FULL

A week later, on Sunday, 10th May, 1896, Lloyd's Weekly Newspaper published a more detailed account of the confession, which had been made to his lawyer, William Stamford Lawton:-

THE AMERICAN JACK THE RIPPER

Carl Feigenbaum, who was executed in the electric chair at Sing Sing last week, is reported to have left a remarkable confession with his lawyer.

The account of the lawyer reads:-

"I have a statement to make, which may throw some light on the murder for which the man I represented was executed.

Now that Feigenbaum is dead and nothing more can be done for him in this world, I want to say as his counsel that I am absolutely sure of his guilt in this case, and I feel morally certain that he is the man who committed many, if not all, of the Whitechapel murders.

Here are my reasons, and on this statement I pledge my honour.

When Feigenbaum was in the Tombs awaiting trial I saw him several times.

The evidence in his case seemed so clear that I cast about for a theory of insanity. Certain actions denoted a decided mental weakness somewhere.

When I asked him point blank, "Did you kill Mrs. Hoffman?", he made this reply:- "I have for years suffered from a singular-disease, which induces an all absorbing passion; this passion manifests itself in a desire to kill and mutilate the woman who falls in my way.

At such times I am unable to control myself."

On my next visit to the Tombs I asked him whether he had not been in London at various times during the whole period covered by the Whitechapel murders?

"Yes, I was," he answered.

I asked him whether he could not explain some of these cases: on the theory which he had suggested to me, and he simply looked at me in reply."

The statement, which is a long one, proves conclusively that Feigenbaum was more or less insane, but the evidence of his identity with the notorious Whitechapel criminal is not satisfactory."

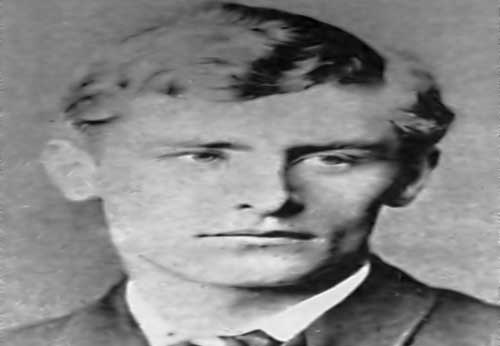

HUGH O PENTECOST DISAGREED

The suggestion that Feigenbaum was the perpetrator of the Whitechapel murders depends very much on the veracity of William S. Lawton's account of the confession that he supposedly made to him.

In truth, there is no compelling evidence to suggest that Lawton may have been lying about what his client had told him, and it might just have been that Feigenbaum may have thought that, in confessing to the Whitechapel murders, he would buy him a little extra time.

However, Feigenbaum's other attorney, Hugh O. Pentecost, whilst expressing his belief that he had no doubt about Feigenbaum having committed the murder of Mrs. Hoffman, disagreed with the claim that Feigenbaum had been jack the Ripper.

The New York Times, presented his objections in its edition of Wednesday, 29th April, 1896:-

The suggestion by William S. Lawton that his client, Carl Ferdinand Feigenbaum, or Anton Zahn, who was put to death at Sing Sing on Monday, for killing Juliana Hoffman, on Sept. 1, 1894, may have been "Jack the Ripper", the Whitechapel murderer, was accepted by few as worthy of investigation.

Lawyer Lawton maintained nothing in his suggestion, and based it on his opinion that Feigenbaum had homicidal mania, his secretive and crafty nature, an unsatisfactory admission by Feigenbaum that he was in London when the crimes of "the Ripper" were committed, and an off-hand declaration by a physician that blood on the knife used to kill Mrs. Hoffman might have been on it for a year.

This theory is confronted with a declaration made by Dr. L. Forbes Winslow, the alienist, published in the New York Times Sept. 1, 1895, that the Whitechapel murders were committed by a medical student of good family, whose mind was wrecked by study. His insanity took the form of religious fervor and homicidal impulse. He was found and incarcerated in a penal asylum. No anatomical murder occurred after his arrest.

"I do not like", said Hugh O. Pentecost, who was Mr. Lawton's associate in the defense of Feigenbaum, "to spoil a good story, but I take no stock in my colleague's story myself, while, as to facts, Mr. Lawton, of course, is able to tell more than I, as I only knew our client to talk to through an interpreter.

"In Feigenbaum, I found nothing in his homicidal method to remind me of "the Ripper". Yes, one fact, perhaps - the absence of blood on him after the killing. Of course as was brought out on the trial, he had an opportunity to wash himself at a sink, and a policeman said that at the First Avenue Station House Feigenbaum had what appeared to be blood on one of his hands."

"That Feigenbaum killed Mrs. Hoffman I haven't a particle of doubt. The motive for the crime never was clear. I believe that the theory of the People that my client was surprised while endeavoring to steal a small sum of money was an expedient."

"Feigenbaum was insane. I have no doubt of that, although Dr. Carlos F. MacDonald certified that he was sane. He was a somewhat curious individual, with no small amount of instruction, and he wrote me some excellent letters in German about his case when in prison. The handwriting was better than you could expect from a practical flower gardener, and the subject of the correspondence - the mythical Jacob Weibel, whom he accused of the murder - was well treated."

Assistant District Attorney Vernon M. Davis, who prosecuted Feigenbaum, said:-

"If it were proved that Feigenbaum was "Jack the Ripper", it would not greatly surprise me, because I always considered him a cunning fellow, surrounded by a great deal of mystery, and his life history was never found out. Of course, the statement of Dr. Winslow about "the Ripper" should receive the consideration it deserves. The case was an odd one, and the People had to furnish a motive for the murder. This was the money which was kept in Mrs. Hoffman's closet or trunk."