- A shawl that was reputedly found by the body of Catherine Eddowes has recently been subjected to DNA analysis.

- The scientists who carried out the analysis claimed that they found the DNA of major suspect Aaron Kosminski and of Catherine Eddowes on the shawl.

- However, the provenance of the shawl, and the science behind the claim have both been questioned, and critics say that the evidence just isn't strong enough to declare the case closed just yet.

- Site Author and Publisher Richard Jones

- Richard Jones

THE DNA AND THE SHAWL

HAS DNA PROVED JACK THE RIPPER'S IDENTITY?

CATHERINE EDDOWES'S SHAWL

There has been a huge amount of excitement in recent years over a shawl that, so it is claimed, was found at the site of the murder of Catherine Eddowes, in Mitre Square, and then taken away from the scene by a police officer by the name of Amos Simpson, who took it home and gave it to his wife as a present.

In 2014 the shawl was subjected to DNA analysis, and certain stains tested positive for the comparative DNA taken from descendants of one of the major suspects, Aaron Kosminski, and of the victim herself, Catherine Eddowes.

Suddenly, it seemed that a mystery that had fascinated and baffled amateur and professional sleuths alike for over 125 years had finally been solved, and there followed a frenzy of press reports claiming that Jack the Ripper had at last been conclusively identified.

Unfortunately, as is so often the case with the Whitechapel murders, this initial euphoria soon gave way to a flurry of doubts and denunciations, as it quickly became apparent that the DNA evidence was not conclusive, and the historical provenance of the shawl, and the fact that it had ever belonged to, or been worn by, Catherine Eddowes was, to say the least, questionable.

A LIKELY SUSPECT

Now, don't get me wrong, Aaron Kosminski has long been a chief contender for the mantle of having been Jack the Ripper.

Indeed, he seems to have been the favoured suspect of the two highest ranking police officers with direct responsibility for the case, Robert Anderson, the head of the Criminal Investigation Department at the time of the murders, and Chief Inspector Donald Swanson, the officer tasked with reading and assessing all the information on the crimes from September, 1888 onwards.

Writers, such as Martin Fido and Paul Begg were putting forward the case against him long before a shawl of uncertain origin became a part of the mystery.

In my documentary on the case, Unmasking Jack The Ripper, made in 2004, we also put Kosminski forward as the most likely of all the known suspects, albeit I have always added the caveat that there is a likelihood that the actual murderer is not one of the known suspects.

DNA, THE GREAT PANACEA OF CRIME INVESTIGATION

So, Kosminski is not a new suspect.

What was different this time was the fact that DNA evidence had, so it appeared, linked this major suspect with one of the victims of Jack the Ripper - and the press was cock-a-hoop that the most infamous murderer in the history of crime had finally been brought to justice.

Unfortunately, the majority of the newspaper articles that heralded this major breakthrough were written by journalists who had little actual knowledge of the case, and whose knowledge of crime solving was very much from the CSI and Criminal Minds school of policing in which DNA evidence is the great panacea, guaranteed to solve any case in 59 minutes of air time, minus, of course, the commercial breaks!

IT ALL STARTS WITH THE CRIME SCENE

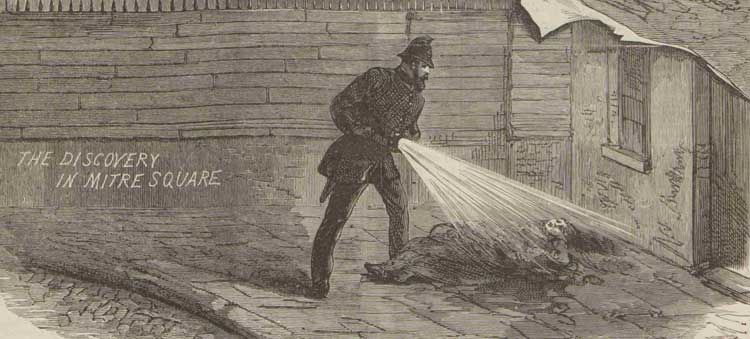

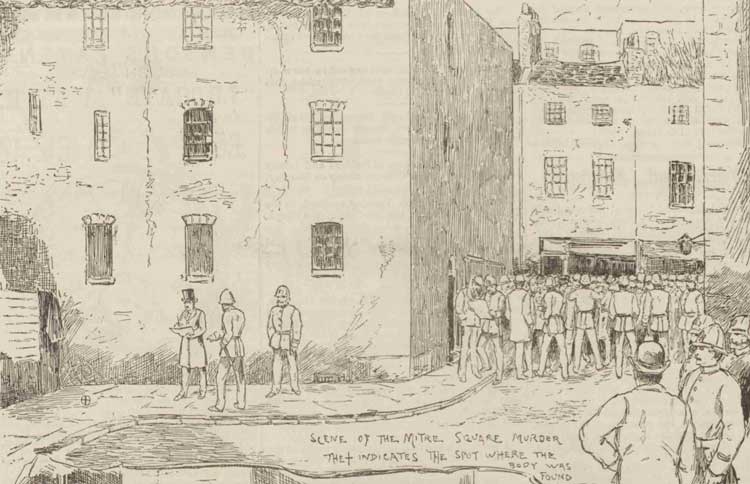

However, before we come to the provenance of the shawl and the reliability of the DNA evidence, we need to begin at the beginning and pay a visit to the scene of the crime following the discovery of the body of Catherine Eddowes in Mitre Square, by Police Constable Watkins, at 1.45am on the 30th September, 1888.

The first important point to note is that Mitre Square was on the eastern fringe of the City of London, and, as a result, it came within the jurisdiction of the City of London Police, not the Metropolitan Police, as had been the case with the previous murders.

In other words, a different police force was responsible for investigating the murder of Catherine Eddowes than had been, and would be, responsible for investigating the other Whitechapel murders.

PC Watkins Finding The Body Of Catherine Eddowes.

Penny Illustrated Paper, Saturday, 6th October, 1888

Copyright, The British Library Board.

THE CHAIN OF EVENTS

Neil Bell, author of Capturing Jack the Ripper, and one of the most respected names in the field of Ripper studies, has this to say about the crime scene investigation as it would have been carried out by the City of London Police:-

The minute Watkins arrived in Mitre Square and discovered the body, he had a set series of "goals" to achieve.

Those goals were:-

- 1. To see if he could help her stay alive. Whilst it was clear that she was, unfortunately, murdered, it wasn't up to him to make that call, only a medical man could have pronounced life extinct. So the initial call would have been to send for a doctor.

- 2. His next duty would have been to maintain the crime scene as best he could, until his superiors arrived - for whom he would have sent after summoning the doctor - Watkins was the lead until their arrival.

- 3. Whilst waiting, Watkins would have effectively started the investigation; for example, he would have checked Catherine's chemise for fingerprints. Any info gleaned would be noted and passed on to CID.

- 4. Mitre Square was a busy scene. CID arrived in minutes and departed in the hunt for the murderer. Medical men arrived also, and later the top brass.

However, the one thing about Mitre Square was that it was an enclosed square, so it was easy to contain. Barring the first minutes of initial confusion, the public was pretty much kept at a distance from the corner where the murder had occurred."

A THOROUGH INVESTIGATION

Within moments of having discovered the body, PC Watkins had summoned assistance, and soon Police Constable Holland, Sergeant Jones and other officers had arrived at the scene.

The speed with which the City of London Police took control of the scene was applauded by The Scotsman on Monday, 1st October, 1888:-

As showing the promptitude with which the City Police acted, it may be mentioned that a message despatched to Bishopsgate Without Police Station to Inspector Collard was, within a quarter of an hour, answered by the officer in person, and he at once took charge of the case until the arrival shortly afterwards of Major Henry Smith, from Cloak Lane, and Superintendent Foster, from Old Jewry, to whom messengers had been sent.

The authorities in the City at once determined that no clue should be sacrificed by ill-considered haste. Every step of the inquiry, which was straight away commenced, was carefully and systematically taken."

SOME OF HER POSSESSIONS

The extent to which the City Police sought to preserve the crime scene, and the thoroughness with which they recorded the condition of the body and the possessions found on and around the deceased is amply demonstrated by the following excerpt from Inspector Collard's inquest testimony, which appeared in The Globe on Thursday, 4th October, 1888:-

Police-Inspector Edward Collard said that, at five minutes before two on Sunday morning last, he received information at Bishopsgate Police-station that a woman had been murdered in Mitre-square.

Information was telegraphed to headquarters, and a constable was despatched for a doctor.

On proceeding himself to Mitre-square, he found there Dr. Sequeira, several police officers, and the deceased, lying in the south-west corner of the square.

The body was not touched till the arrival of Dr. Brown, who came to the square shortly after the witness.

The medical men examined the body, and Sergeant Jones picked up some small buttons and other articles, including small mustard tin, which contained two pawn tickets."

The Police Examine The Crime Scene And Keep The Crowds Out Of Mitre Square.

Penny Illustrated Paper, Saturday, 13th October, 1888

Copyright, The British Library Board.

MORE DETAILS ON THE POSSESSIONS

The next day, The London Daily News revealed a little more from the inspector's testimony concerning what the police had found at the crime scene:-

The body was not touched until Dr. Gordon Brown shortly afterwards arrived.

The medical gentleman examined her, and, in my presence, Sergeant Jones picked up from the footway, on the left side of the deceased, three small black buttons, of the kind generally used for women's boots, a small metal button, a common metal thimble, a small mustard tin containing two pawn tickets."

THE OFFICIAL LIST OF HER CLOTHING AND POSSESSIONS

Once the City Police and the doctor had finished their investigations and examinations at the scene of the crime, the body was removed to the Golden Lane mortuary in the City of London.

Here it was stripped, and Inspector Collard painstakingly went through every item of clothing and artefacts and painstakingly compiled an incredibly detailed and descriptive list of the deceased's possessions, even going so far as to count the blood spots on her right boot.

CATHERINE EDDOWES POSSESSIONS

- Black straw bonnet trimmed with green & black velvet and black beads, black strings. The bonnet was loosely tied, and had partially fallen from the back of her head, no blood on front, but the back was lying in a pool of blood, which had run from the neck."

- "Black Cloth Jacket, imitation fur edging round collar, fur round sleeves, no blood on front outside, large quantity of Blood inside & outside back, outside back very dirty with Blood & dirt, 2 outside pockets, trimmed black silk braid & imitation fur."

- "Black straw bonnet trimmed with green & black velvet and black beads, black strings. The bonnet was loosely tied, and had partially fallen from the back of her head, no blood on front, but the back was lying in a pool of blood, which had run from the neck."

- "Black Cloth Jacket, imitation fur edging round collar, fur round sleeves, no blood on front outside, large quantity of Blood inside & outside back, outside back very dirty with Blood & dirt, 2 outside pockets, trimmed black silk braid & imitation fur."

- "Chintz Skirt 3 flounces, brown button on waistband, Jagged cut 62 inches long from waistband, left side of front, Edges slightly Bloodstained, also Blood on bottom, back & front of skirt."

- "Brown Linsey Dress Bodice, black velvet collar, brown metal buttons down front, blood inside & outside back of neck & shoulders, clean cut bottom of left side, 5 inches long from right to left."

- "Grey Stuff Petticoat, white waist band, cut 4 inch long, thereon in front, Edges blood stained, blood stains on front at bottom of Petticoat."

- "Very Old Green Alpaca Skirt, Jagged cut 10 inches long in front of waistband downward, blood stained inside, front under cut."

- "Very Old Ragged Blue Skirt, red flounce, light twill lining, jagged cut 101 inches long, through waist band, downward, blood stained, inside & outside back and front."

- "White Calico Chemise, very much blood stained all over, apparently torn thus in middle of front."

- "Mans White Vest, button to match down front, 2 outside pockets, torn at back, very much Blood stained at back, Blood & other stains on front."

- "Pair of Mens lace up Boots, mohair laces, right boot has been repaired with red thread, 6 Blood marks on right boot."

- "No Drawers or Stays."

- "1 piece of red gauze Silk, various cuts thereon found on neck."

- "1 large White Handkerchief, blood stained."

- "2 Unbleached Calico Pockets, tape strings, cut through also top left hand corners, cut off one."

- "1 Blue Stripe Bed ticking Pocket, waist band, and strings cut through, (all 3 Pockets) Blood stained."

- "1 White Cotton Pocket Handkerchief, red and white birds eye border."

- "1 Pr. Brown ribbed Stockings, feet mended with white."

- "12 pieces of white Rag, some slightly bloodstained."

- "1 piece of white coarse Linen."

- "1 piece of Blue & White Shirting (3 cornered.)."

- "2 Small Blue Bed ticking Bags."

- "Short Clay Pipes (black)."

- "1 Tin Box containing Tea."

- "1 do do do Sugar."

- "1 Small Tooth Comb."

- "1 White Handle Table Knife & 1 Metal Tea Spoon."

- "1 Red Leather Cigarette Case, white metal fittings."

- "1 Tin Match Box. empty."

- "1 piece of Red Flannel containing Pins & Needles."

- "1 Ball of Hemp."

- "1 Piece of old White Apron."

NO SHAWL WAS MENTIONED

What is interesting about Collard's inventory is that it makes no mention of a shawl being found on or near to Catherine Eddowes body.

It is also worth noting that the newspaper articles make it more than clear that the City Police were determined to preserve and log every item found at the site of the murder.

Furthermore, once Police Constable Watkins found the body in Mitre Square, the speed with which the City Police sprang into action was truly impressive.

Within minutes of his discovery, at 1.45am, officers were converging on the square from all corners, including several detectives who were already in the vicinity.

At just after 2am, Inspector Collard arrived in the Square and took charge of the scene.

He was later emphatic that the body had not been touched prior to the arrival of Dr. Gordon Brown, and once the medical men were going about their business a thorough examination was carried out during which Sergeant Jones found the previously mentioned items.

Yet, at no time was any mention made of the presence of a shawl matching the one that has recently been the subject of the DNA analysis.

This would have been a major piece of evidence had it been found at the scene.

As Neil Bell puts it:-

This would have been an important garment for the police. It was an outer garment and therefore a key item in the identification of the victim AND her movements. Such an item is essential.

Collard noted her personal items down. These would have been gathered in muslin bags and taken back to storage at Bishopsgate Police Station.

With prisoners charged for serious crime, their clothing would be sent to the laboratory for analysis. Yes, this happened - though whether it was common practice or not I'm not sure.

I see no reason why similar analysis would not have been done with victims clothing - however, that is conjecture on my part."

NOT THERE WHEN COLLARD ARRIVED

However, what cannot be denied is that Collard would have noted the presence of the shawl had it been there when he arrived at the scene. The fact that he made no mention of it in his subsequent reports or at the inquest, suggests that it wasn't at the scene of the crime when he arrived.

Which leaves a window of around sixteen minutes, from Watkins finding the body to Collard's arrival to take charge of the scene, for somebody to have removed such an important item of apparel from the square.

So, who could have taken the shawl?

POLICE CONSTABLE AMOS SIMPSON

Amos Simpson joined the Metropolitan Police in 1868 and was assigned to Y Division, covering Kentish Town.

He was promoted to Acting Sergeant in 1881, and then, in 1886, he was posted to N Division (Islington).

According to family tradition amongst his descendants, he was drafted into the area on "special duties" at the time of the Jack the Ripper murders in 1888 - he may have been one of the officers brought in from other divisions at the height of the scare.

That same family tradition holds that he was the first police officer to find the body of Catherine Eddowes and that he removed the shawl from the crime scene before the arrival of other officers.

HE WAS METROPOLITAN POLICE

There are several inconsistencies between this "family tradition", and the official and newspaper accounts of the immediate aftermath of the murder.

Firstly, it is just that - a "family tradition", and, to be frank, family traditions have little basis in historical fact. Indeed, I would conjecture that many London police officers, not to mention a few outside London, happily entertained their children and grandchildren with tales of how they came close to catching Jack the Ripper, or how they were the ones who found the body of a particular victim.

Secondly, there is, as far as I can tell, no official record of Amos Simpson's having been the officer who found the body of Catherine Eddowes, nor, for that matter, of him actually being anywhere near the scene of the crime.

Thirdly, Amos Simpson was a Metropolitan Police officer, whereas the murder of Catherine Eddowes took place in the City of London; which begs the question, what was a Metropolitan Police officer doing interfering at a crime scene that came under the jurisdiction of the City of London Police?

Fourthly, there is no actual proof that Amos Simpson himself actually claimed that he was the officer who found the body and that he then removed the shawl from the crime scene. And, even if he did make the claim, it is not borne out by the known facts. He wasn't mentioned in the newspapers, he wasn't called as a witness at the inquest - in fact, officially at least, he is conspicuous by his absence at the scene of the murder of Catherine Eddowes.

As Neil Bell puts it:-

If Simpson had been in Mitre Square, then I cannot see him having a lead role, i.e. being near to Catherine Eddowes' body. Watkins doesn't mention him, Collard doesn't mention him.

Therefore, his role in the Square, if he was present, would have been to maintain order until the reserve arrived.

Now, this is where the story goes a little pear-shaped.

Once the reserve arrived, he would be expected to return to his beat.

So, either he carried this shawl around with him for the remainder of his beat (until 6am), or he stored it somewhere with a view to picking it up later.

If the latter, then he would have picked it up after being stood down from duty, as no doubt questions would have been raised otherwise."

WHAT SORT OF OFFICER WAS HE?

Of course, if Simpson did remove the shawl from Mitre Square, then he committed a grave dereliction of duty, and one that could have exposed him to severe disciplinary action had it been found out.

And yet, from what we know of Simpson's police career, he was an assiduous and dedicated officer, with around twenty years experience.

Would he honestly have risked all that to acquire an item of apparel that can have seemed of little use or value to him at the time?

As Neil Bell puts it:-

He was an extremely experienced policeman, with a decent record if I recall rightly.

With that in mind, is it reasonable to assume he would have known the impact of removing such a key item, both to the investigation and him personally?

If you feel that you know the answer to that, then the only remaining question is this .... would he?"

THE DNA AND THE SHAWL

Of course, this brings us to the problem of the DNA of a major suspect and the DNA of a Jack the Ripper victim both being on the same shawl.

After all, it is this that makes the story so newsworthy today, 100 years after the death of that suspect, Aaron Kosminski, on 24th March, 1919.

But before we can decide whether it has been proved beyond any reasonable doubt that Kosminski was the murderer, we must confront the awkward fact that the shawl almost certainly wasn't in Mitre Square when the first police officer arrived on the scene moments after the murder had been committed.

THERE IS SCANT EVIDENCE

Dr. Drew Gray, author of The Police Magistrate Blog, is a social historian of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries who specialises in the history of crime and punishment, and whose forthcoming book, Jack and the Thames Torso Murders: A New Ripper? will be published in June 2019.

Dr. Gray is emphatic that the shawl was not present at the scene of the murder, nor that it ever belonged to Catherine Eddowes:-

In my opinion, there is no evidence to suggest that a shawl was ever found in Mitre Square or that it belonged to Catherine Eddowes.

It goes against reason that Eddowes and Kelly, both broke and desperate for money to pay for lodgings and food, would retain possession of a seemingly valuable shawl that they might have pawned for a few shillings.

I am not convinced at all by Kosminski's candidacy; he fits the "outsider" model of the killer (along with various doctors and "gentleman Rippers") and the only reason we keep returning to that unholy trio is the Macnaghten memorandum, which I think has been given far too much weight by researchers.

"Bad" science has been co-opted here to back up "bad" history: any DNA that was on the shawl would have degraded in the 130 plus years since 1888, and the item has been further corrupted by the number of hands it has passed through in the meantime.

As is so often the case in Ripperology "evidence" is being manipulated to fit a thesis, to make 2+2=5, and this takes us no nearer to solving the case than we were before."

THE STAINS ON THE SHAWL

The shawl itself is stained by what appears to be blood and by other stains that it is claimed are semen, and it is these stains that have been the subject of the analysis - the blood being, so it has been claimed, that of Catherine Eddowes, and the semen being that of Aaron Kosminski.

Without one or both of these been proven as having belonged to either the victim or the suspect, then the case for Kosminski's guilt ceases to exist.

In the opinion of Paul Guidry, a researcher in criminology and crime history:-

Assuming that Eddowes did actually own this shawl, we should find it odd that it is not mentioned at the crime scene, nor is it listed in the police inventory of Eddowes' personal items.

The DNA present on the shawl is, supposedly, of Eddowes' blood and another sample of semen, but the two samples were not necessarily deposited at the same time.

Let's suppose for a second that it is a sample from Aaron: unless we can definitively rule out the notion that Aaron Kosminski paid Eddowes for sex at some point, then this DNA test proves nothing."

IS IT ACTUALLY A SHAWL?

One of the first problems that needs to be addressed is whether the garment in question actually is a shawl?

After all, it is, in its entirety, a good eight feet long by two feet wide, meaning that it would have swamped its wearer to the point of being cumbersome - not to mention the fact that it would be extremely difficult for a police officer to have smuggled it away from the crime scene unheeded.

It has been conjectured that the item is, in fact, a table runner, rather than a shawl, and its length would appear to substantiate this.

A GIFT FOR HIS WIFE

But, let us suppose that it is a shawl, that it does date from the 1880's, and that it did belong to Catherine Eddowes.

According to the aforementioned "family tradition", Police Constable Amos Simpson, having removed the shawl from the scene of the murder of Catherine Eddowes, took it home as a present for his wife.

Not impressed by the romance of the gesture of her husband bringing her home a blood and semen stained shawl - as opposed to, let's say, a dozen red roses or a box of chocolates - Mrs. Simpson told her other half that she didn't want it in their house.

Simpson, however, didn't dispose of it, but put it in a cupboard, and from that point on it was passed down through the various generations of the Simpson family, each recipient being assured that it had belonged to Jack the Ripper victim Catherine Eddowes.

A TIMELINE OF THE SHAWL

For the more recent history in the timeline of this intriguing artefact, I turned to Jonathan Menges, the creator and host of Rippercast, a podcast devoted to discussing the Whitechapel murders:-

The shawl first came to the attention of the Ripperology community some thirty or so years ago.

There are, in fact, several pieces of the shawl in circulation, including the main section, which is the one that has recently been the subject of scientific analysis,

In 1988, Paul Harrison, whilst researching his book Jack The Ripper: The Mystery Solved, was notified that John and Janice Dowler, owners of a video rental shop in Essex, were in possession of a shawl that had, so it was claimed, once been the property of Catherine Eddowes.

As it transpired, what they did, in fact, have, were two pieces of the garment that had been framed together. They stated that they had acquired it in exchange for a first edition of the Radio Times from David Meville Hayes, the great, great nephew of Amos Simpson.

Hayes had cut two pieces from a larger parent piece which, in its original state, measured eight feet long by two feet wide. He had framed the smaller pieces, and it was these that he exchanged with the Dowlers.

In the mid-1990s, the Dowlers sold the framed segments to an antique dealer who sold them to Ripperologists Andy and Sue Parlour.

As for the main body of the shawl, in around 1993, David Hayes loaned it to the Metropolitan Police's Black Museum, who approached auctioneers Sotheby's and asked them to put a possible date on it.

Sotheby's concluded that the item dated from the early 1900's.

In 2007, this main piece of the shawl was put up for auction and was bought by businessman Russell Edwards, who had, prior to making an offer, contacted Scotland Yard's crime museum to verify the authenticity of the "shawl" and had been told by the museum's curator that the ripper case had been solved, and that the murderer was Aaron Kosminski."

DNA EXTRACTED FROM THE SHAWL

Sensing that he was onto something major, Russell Edwards submitted the shawl for scientific analysis to Dr. Jari Louhelainen, Senior Lecturer in Molecular Biology at Liverpool John Moores University in the United Kingdom.

Dr. Louhelainen managed to extract DNA from some of the blood and was then able to obtain mitochondrial DNA results.

WHAT IS MITOCHONDRIAL DNA?

I have to confess that science has never been a forte of mine, so for the definition of what mitochondrial DNA is I have turned to Wikipedia:-

Mitochondrial DNA is the small circular chromosome found inside mitochondria. These organelles found in cells have often been called the powerhouse of the cell. The mitochondria, and thus mitochondrial DNA, are passed almost exclusively from mother to offspring through the egg cell."

TESTING THE DNA

Meanwhile, Russell Edwards had approached a matrilineal descendant of Catherine Eddowes - her great, great, great-granddaughter - who provided a DNA sample which was then matched against the blood stains on the shawl, and, so it was claimed, the mitochondrial DNA matched.

This was presented as proof that the blood on the shawl was, indeed, that of Catherine Eddowes.

Edwards and Louhelainen next enlisted the assistance of Dr. David Miller who found surviving epithelium cells - a type of tissue that coats organs, in this case, thought to have come from the urethra during ejaculation - in other stains on the shawl.

The next challenge was to find a descendant of Aaron Kosminski who was willing to provide a sample of their DNA which could then be tested in order to prove that they were descended from Jack the Ripper.

Since Kosminski was childless, finding a direct descendant was a non-starter.

However, they did manage to find a descendant of Aaron Kosminski's sister, Matilda, and this descendant agreed to provide the necessary DNA sample.

Here is what Louhelainen said about the findings:-

Then I used a new process called whole genome amplification to copy the DNA 500 million-fold and allow it to be profiled.

Once I had the profile, I could compare it to that of the female descendant of Kosminski's sister, who had given us a sample of her DNA swabbed from inside her mouth.

The first strand of DNA showed a 99.2 per cent match, as the analysis instrument could not determine the sequence of the missing 0.8 per cent fragment of DNA. On testing the second strand, we achieved a perfect 100 per cent match.

Because of the genome amplification technique, I was also able to ascertain the ethnic and geographical background of the DNA I extracted.

It was of a type known as the haplogroup T1a1, common in people of Russian Jewish ethnicity.

I was even able to establish that he had dark hair."